|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

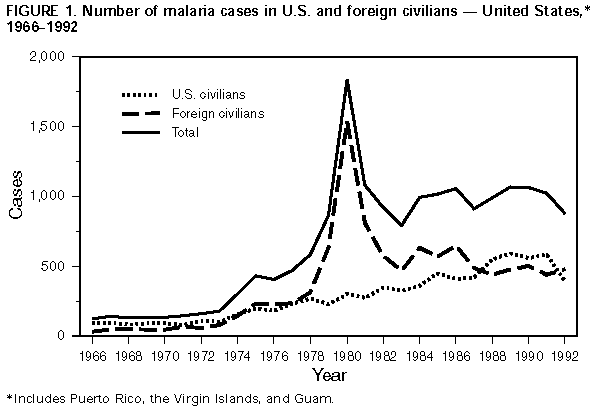

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Malaria Surveillance -- United States, 1992Abstract Problem/Condition: Malaria is caused by one of four species of Plasmodium (i.e., P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, or P. malariae) and is transmitted by the bite of an infective female Anopheles sp. mosquito. Most malaria cases in the United States occur among persons who have traveled to areas that have ongoing transmission. However, cases are transmitted occasionally through exposure to infected blood products, by congenital transmission, or by local mosquito-borne transmission. Malaria surveillance is conducted to identify episodes of local transmission and to guide prevention recommendations. Reporting Period Covered: Cases with onset of illness during 1992. Description of System: Malaria cases were identified at the local level (i.e., by health-care providers or through laboratory-based surveillance). All suspected cases were confirmed by slide diagnosis and then reported to the respective state health department and to CDC. Results: CDC received reports of 910 cases of malaria that had onset of symptoms during 1992 among persons in the United States and its territories. In comparison, 1,046 cases were reported for 1991, representing a decrease of 13% in 1992. P. vivax, P. falciparum, P. malariae, and P. ovale were identified in 51%, 33%, 4%, and 3% of cases, respectively. The species was not identified in the remaining 9% of cases. The number of reported malaria cases that had been acquired in Africa by U.S. civilians decreased 38%, primarily because the number of P. falciparum cases declined. Of U.S. civilians whose illnesses were diagnosed as malaria, 81% had not taken a chemoprophylactic regimen recommended by CDC. Seven patients had acquired their infections in the United States. Seven deaths were attributed to malaria. Interpretation: The decrease in the number of P. falciparum cases in U.S. civilians could have resulted from a change in travel patterns, reporting errors, or increased use of more effective chemoprophylaxis regimens. Actions Taken: Additional information was obtained concerning the seven fatal cases and the seven cases acquired in the United States. Malaria prevention guidelines were updated and disseminated to health-care providers. Persons traveling to a malaria-endemic area should take the recommended chemoprophylaxis regimen and use personal protection measures to prevent mosquito bites. Any person who has been to a malarious area and who subsequently develops a fever or influenza-like symptoms should seek medical care, which should include a blood smear for malaria. The disease can be fatal if not diagnosed and treated at an early stage of infection. Recommendations concerning prevention and treatment of malaria can be obtained from CDC. INTRODUCTION Malaria is caused by infection with one of four Plasmodium species (i.e., P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae) that can infect humans. The infection is transmitted by the bite of an infective female Anopheles sp. mosquito. Forty percent of the world's population live in areas where malaria is transmitted (e.g., parts of Africa, Asia, Central America, Hispaniola, North America, Oceania, and South America). In the past, malaria was endemic throughout much of the continental United States; more than an estimated 600,000 cases occurred during 1914 (1). During the late 1940s, a combination of improved socioeconomic conditions, water management, vector-control efforts, and case management was successful at interrupting malaria transmission in the United States. Since then, surveillance has been maintained to detect reintroduction of transmission. Through 1992, almost all cases of malaria in the United States were imported from regions of the world where malaria transmission was known to occur. Each year, several cases that had been acquired in the United States either by blood-induced or congenital transmission were reported. In addition, cases that might have been mosquito-borne infections acquired in the United States were occasionally reported. State and/or local health departments and CDC thoroughly investigate all locally acquired malaria cases, and CDC conducts an analysis of all imported cases to detect trends in acquisition. This information is used to guide malaria prevention recommendations for persons who travel abroad. For example, an increase in P. falciparum malaria among U.S. travelers to Africa, an area with increasing chloroquine-resistance, led CDC in 1990 to change the recommended chemoprophylaxis from chloroquine to mefloquine (2). The signs and symptoms of malaria illness are variable, but most patients experience fever. Other symptoms often include headache, back pain, chills, increased sweating, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and cough. The diagnosis of malaria should be considered for any person who has these symptoms and who has traveled to an area that has malaria transmission. Untreated P. falciparum infection can progress to coma, renal failure, pulmonary edema, and death. Asymptomatic parasitemia can occur among persons who have been long-term residents of malaria-endemic areas. This report summarizes malaria cases reported to CDC for 1992. METHODS Sources of Data Malaria surveillance is a passive system; cases are identified at the local level by health-care providers and/or laboratories. All suspected cases are confirmed by slide diagnosis. A slide-confirmed case is reported to the state health department and to CDC on a standard form that contains clinical, laboratory, and epidemiologic information. CDC staff review all reporting forms at the time of receipt and request additional information if necessary (e.g., when travel to a malaria-endemic country was not reported). Reports of other cases are telephoned directly by health-care providers to CDC, usually when assistance with diagnosis or treatment is requested. All cases that have been acquired in the United States are investigated, including all induced and congenital cases and possible introduced or cryptic cases. Information from uniform case report forms is entered into a data base and analyzed annually. Definition of Terms The following definitions are used in this report:

This report also uses terminology derived from the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) (3). Definitions of the following terms are included for reference.

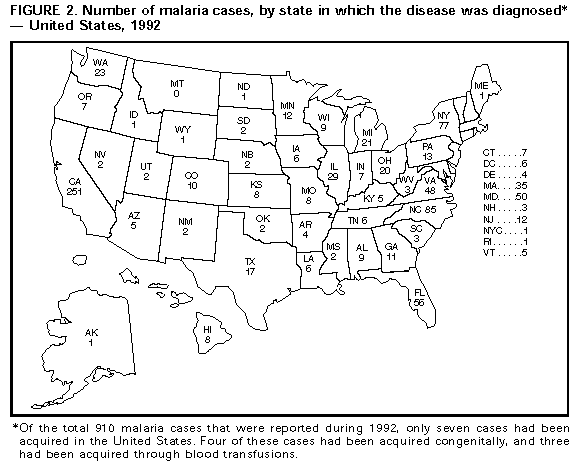

malaria occurs regularly. case in an area where malaria does not occur regularly. The early diagnosis of malaria requires that physicians consider malaria in the differential diagnosis of every patient who has a fever; the examination of such patients should include taking a comprehensive travel history. If malaria is suspected, a Giemsa-stained smear of the patient's peripheral blood should be examined for parasites. Thick and thin blood smears must be prepared properly because the accuracy of diagnosis depends on the quality of the blood film and the experience of the laboratory personnel. (See Appendix A for proper procedures necessary for accurately diagnosing malaria.) RESULTS General Surveillance CDC received reports of 910 malaria cases that had onset of symptoms during 1992 among persons in the United States and its territories. In comparison, 1,046 cases were reported for 1991 (4). In 1992, seven of the 910 persons acquired the infection in the United States. Most of the malaria cases reported each year since 1973 have occurred in civilians Table_1. In 1992, 394 cases occurred in U.S. civilians, representing a 33% decrease in the 585 cases reported for 1991 Figure_1. However, the number of cases in foreign civilians increased 10%, from 439 cases in 1991 to 481 cases in 1992. Only 29 cases occurred in U.S. military personnel during 1992. Plasmodium Species The Plasmodium species was identified in 826 (91%) of the 910 cases. In 1992, P. vivax and P. falciparum were identified in blood from 51% and 33% of infected persons, respectively Table_2. The 296 P. falciparum cases reported for 1992 represented a 28% decrease from the 410 cases reported for 1991. Area of Acquisition and of Onset of Illness Most malaria cases had been acquired in Africa (337 {37%} cases) and Asia (330 {36%} cases) Table_3. In the United States, cases were reported by the state in which the disease was diagnosed Figure_2. Interval Between Arrival and Illness Of those persons who became ill with malaria after arriving in the United States, the interval between the dates of arrival and the onset of illness was known for 554 of the persons for whom the infecting Plasmodium species was also identified. The infecting species was not identified for an additional 41 cases. Clinical malaria developed within 1 month after the person's arrival in 175 (88%) of the 198 P. falciparum cases and in 100 (32%) of the 316 P. vivax cases Table_4. Only 16 (3%) of the 554 persons became ill greater than or equal to 1 year after their arrival in the United States. An additional 40 persons reported becoming ill before arriving in the United States. Half of these persons developed symptoms within 1 week before arrival; the remainder reported that symptoms began 7-105 days before arrival. Imported Malaria Cases Imported Malaria in Military Personnel Twenty-nine cases of imported malaria in U.S. military personnel were reported for 1992. Twenty-one of these cases occurred in personnel of the U.S. Army; four cases, the U.S. Marine Corps; two cases, the National Guard; one case, the U.S. Air Force; and one case, the U.S. Navy. Imported Malaria in Civilians Of the 868 imported malaria cases in civilians, 387 (45%) occurred in U.S. citizens and 481 (55%) in citizens of other countries Table_5. Of the 387 imported malaria cases in U.S. civilians, 190 (49%) had been acquired in Africa Table_5, representing a 38% decline in the 308 imported cases acquired in that region during 1991. Eighty-nine (23%) of the imported cases reported for 1992 had been acquired in Asia. Of the 481 imported cases in foreign civilians, 233 (48%) had been acquired in Asia and 142 (30%) in Africa. Use of Chemoprophylaxis Information concerning use of chemoprophylaxis was known for 349 (90%) of the 387 U.S. civilians who had imported malaria. Of these 349 persons, 178 (51%) had not taken chemoprophylaxis, 104 (30%) had not taken a drug recommended by CDC for the area visited, and only 67 (19%) had taken the correct medication as recommended by CDC (5). Of these 67 cases, 37 were consistent with relapse infections caused by P. vivax or P. ovale, and 17 cases could not be assessed because of incomplete information. Of the remaining 13 persons who reported having taken the correct medication, four persons had taken the recommended dosage and nine persons had not. The purpose of travel to foreign countries with known malaria transmission was reported for 278 (72%) of the 387 U.S. civilians who had imported malaria cases. Of the 387 civilians, the largest percentage (14%) had traveled to visit friends and relatives Table_6. Malaria Acquired in the United States Congenital Malaria The following four cases of congenitally acquired malaria were reported for 1992. Case 1. During February 1992, a 3-week-old boy was admitted to a hospital in California because of febrile episodes. An examination of the infant's blood smear demonstrated the presence of P. vivax parasites. He was treated with chloroquine, and his recovery was uneventful. His mother had visited Honduras, her native country, during January 1992. An examination of the mother's blood smears also demonstrated the presence of P. vivax parasites. She was treated with chloroquine and primaquine. Case 2. A 5-week-old girl who had been born in California began having febrile episodes during March 1992. The infant remained ill, and she was hospitalized in May because of fever, cough, and lack of appetite. An examination of her blood smear demonstrated the presence of P. malariae parasites. She was treated with chloroquine, and her recovery was uneventful. The infant's mother, a native of Laos, had emigrated to the United States in 1984. She had not traveled to a malarious area since then, and she had not reported having febrile episodes during the pregnancy or delivery. After malaria was diagnosed in the infant, the mother's blood was examined for malaria parasites. Although the mother's blood smear results were negative, her blood sample had a positive reaction with an indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) assay titer of 1:4,096 for P. malariae. She was treated with chloroquine. Case 3. During May 1992, a 4-week-old boy who had been born in California was hospitalized because of febrile episodes. An examination of the infant's blood smear demonstrated the presence of P. vivax parasites. He was treated successfully with chloroquine. The infant's mother had been born in Mexico and had come to the United States 1 month before delivery. No malaria parasites were detected in her blood smears, and she received presumptive treatment. Case 4. During June 1992, a 4-week-old girl who had been born in New York was admitted to a hospital in New York City because of fever, splenomegaly, and anemia. An examination of the infant's blood smear demonstrated the presence of P. vivax parasites. She received a blood transfusion and was treated with chloroquine; her recovery was uneventful. The infant's mother, a native of Honduras, had been in the United States since August 1991. The mother had been hospitalized at 37 weeks' gestation because of anemia and thrombocytopenia, and at that time she was diagnosed as having P. vivax infection. However, the infant was born before the mother could receive treatment. After the delivery, the mother was treated with chloroquine and primaquine. A postpartum examination of the infant's blood smear did not demonstrate the presence of malaria parasites. Cryptic Malaria No cases of cryptic malaria were reported for 1992 (6). Induced Malaria The following three cases of blood transfusion-induced malaria were reported. Cases 1 and 2. A 71-year-old female resident of Texas was diagnosed as having idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura during a 2-week hospitalization in August 1992. She was discharged on August 16 but was readmitted on August 23 because of fever, lethargy, and confusion. An examination of the woman's blood smear demonstrated the presence of P. falciparum parasites (approximately 25% of her red blood cells were infected). Although she had not traveled to a malaria-endemic area, she had received a total of 95 units of blood products (5 units of packed red blood cells and 90 units of platelets) during her previous hospitalization. The second case occurred in a 65-year-old male resident of Texas who was diagnosed in August 1992 as having P. falciparum infection. He had not traveled to a malaria-endemic area, but he had received 3 units of packed red blood cells for myelodysplasia during August. Both of these patients (i.e., in cases 1 and 2) had received, during the same time period, blood transfusions in the same city in Texas. The second malaria case was identified while donor recall (i.e., the process of reviewing donor records and contacting each donor for additional information) was being organized for the first case. The review of donor records indicated that none of the donors had provided a history of malaria, malaria treatment, or prophylaxis for malaria, and none had been to a malarious area during the preceding 3 years. However, two donors had contributed blood products to both patients. These two donors were tested for malaria antibodies; a blood sample from one of these donors was negative, but the other donor's blood sample had a positive reaction with an IFA assay titer of 1:4,096 for P. falciparum malaria. The implicated donor was a 19-year-old man who had been born in Nigeria and who had had previous malaria infections. Although he reported symptoms consistent with malaria infection, an examination of his blood smears did not demonstrate the presence of malaria parasites. He had resided in Nigeria through December 1991; at the time of the investigation, he was residing in Utah. He was contacted there by the Utah Department of Health and was treated for P. falciparum malaria. One patient (i.e., the patient described in Case

Case 3. During September 1992, a 44-year-old male resident of California developed renal insufficiency and underwent bilateral nephrectomy. He had had intermittent fevers that had begun in August; in December, he was diagnosed with P. malariae infection. He was treated successfully with chloroquine. He had been born in the United States, and he had not traveled to a malaria-endemic area or used intravenous drugs; however, during the 7 months preceding the onset of malarial symptoms, he had received 4 units of packed red blood cells. The four donors of the packed cell units were tested for malaria antibodies. The blood sample of one donor, the patient's brother, was positive for P. malariae, with an IFA assay titer of 1:1,024. The implicated unit had been transfused in June 1992. An examination of the brother's blood smears did not demonstrate the presence of malaria parasites. The brother had been born in Canton Province, China, and he had moved to the United States in 1948 when he was 11 years of age. He had not traveled since then to a malaria-endemic area or reported symptoms suggestive of malaria infection. He was treated with chloroquine. Deaths Attributed to Malaria During 1992, the following seven deaths were attributed to malaria. Case 1. A 22-year-old female resident of Florida had worked for 6 months as a missionary in Mali, at which time she took chloroquine as prophylaxis for malaria. She became ill approximately 2 weeks after she returned home in January 1992, and she was hospitalized 1 week later on January 30. She was diagnosed as having P. falciparum infection and was treated with intravenous quinidine and tetracycline. She developed renal failure and adult respiratory distress syndrome, and she died on February 12. Case 2. A pregnant resident of New York visited Nigeria with her husband. Her physician had prescribed Fansidar for her to take during the trip as prophylaxis for malaria. On October 21, 1992, she returned to New York. She developed a fever 5 days later, and she was admitted to the hospital on October 26 when she was at 34 weeks' gestation. Her illness was diagnosed as P. falciparum malaria (2% of her red blood cells were infected), and treatment with quinine and clindamycin was initiated. When her clinical condition worsened, her treatment was changed to intravenous quinidine gluconate. She delivered a stillborn infant on October 28, then she became comatose and developed hypotension and respiratory distress. She died on October 30. Case 3. On September 30, 1992, a 53-year-old man returned to his residence in Alabama after teaching in Burkina Faso. He had not taken prophylaxis for malaria. He became ill 2 days after his return, and he sought medical treatment on October 4. On October 5, his physician diagnosed P. falciparum malaria (approximately 15% of his red blood cells were infected) and initiated treatment with oral quinine. The patient could not tolerate oral therapy, and treatment was changed to intravenous quinidine. On October 7, 2 days after starting treatment, he had a grand mal seizure. He died on October 11. Case 4. A 68-year-old female resident of Mexico had traveled to several countries in Africa, including Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Rwanda, and Uganda. She had taken chloroquine as prophylaxis for malaria during her trip. She arrived in Texas on November 9, where she developed a fever the next day. When she was hospitalized on November 12, approximately 25% of her red blood cells were infected with P. falciparum. The patient was treated with intravenous quinidine and an exchange transfusion. She developed multiple complications, including hypotension, renal failure, and adult respiratory distress syndrome. She died on November 21. Case 5. On November 2, 1992, a 70-year-old male resident of India arrived in California, where he became ill on November 10. When he was hospitalized on November 11, 10% of his red blood cells were infected with P. falciparum. At that time, he reported having intermittently taken chloroquine as prophylaxis for malaria while in India. He was treated initially with chloroquine; however, he developed hypoglycemia, mental status changes, and renal failure. Therapy was changed to quinine and doxycycline, then changed again to intravenous quinidine; he also received an exchange transfusion. He died on November 17. Case 6. On October 23, 1992, a 70-year-old male resident of India came to the United States to visit relatives in Illinois. He became ill on November 2 and was hospitalized on November 9. The illness was diagnosed initially as P. vivax infection, and the patient was treated with chloroquine. Further examination of his blood smears demonstrated the presence of P. falciparum (10% of his red blood cells were infected), and treatment was changed to intravenous quinidine and doxycycline. The patient, who had not been on prophylaxis for malaria while in India, died on November 13. Case 7. On July 22, 1992, a 37-year-old male resident of the District of Columbia arrived in New York City after a 15-day trip to Ghana. The patient had been unconscious for 6 hours on the airplane; on arrival in New York, he was febrile, tachycardic, in shock, and intermittently awake. He was transported to a local hospital, where he was treated for multiple organ (including liver and kidney) failure and massive gastrointestinal bleeding and was diagnosed as having P. falciparum infection (approximately 5% of his red blood cells were infected). The patient died several hours later on July 23. An autopsy demonstrated sequestration of P. falciparum asexual parasites in cerebral vessels consistent with a diagnosis of cerebral malaria. Before his death, the patient had reported having taken an unspecified antimalarial medication. DISCUSSION A total of 910 cases of malaria were reported to CDC for 1992, representing a 13% decrease from the 1,046 cases reported for 1991. This decrease primarily reflects the 38% decline in the number of P. falciparum infections acquired by U.S. civilians in Africa, an area with chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum. This latter decrease could be associated with a) changes in travel patterns, b) disease reporting errors, or c) increased use of the more effective mefloquine regimen. The analysis of cases reported for 1993 will enable further assessment of these factors. Chemoprophylaxis use was known for 90% of the U.S. civilians who had imported malaria; 81% of these infections occurred in persons who had not taken a chemoprophylactic regimen recommended by CDC. Only four infections occurred in persons who reported having correctly taken the recommended chemoprophylaxis. In 1990, the recommended drug for preventing chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum malaria was changed to mefloquine, which is highly effective in comparison with chloroquine, the previously recommended medication (7,8). An earlier review of deaths in the United States that were attributed to malaria cited multiple causes for such deaths, including failure to take recommended antimalarial chemoprophylaxis, refusal or delay in seeking medical care, and misdiagnosis (9). A combination of these factors contributed to the seven deaths reported for 1992. None of the travelers who died had taken the chemoprophylactic regimens that CDC recommended at the time the person was traveling. Treatment for malaria should be initiated immediately after the diagnosis has been confirmed by a positive blood smear. Treatment should be determined on the basis of the infecting Plasmodium species, the parasite density, and the patient's clinical status (10). Although non-falciparum malaria rarely causes severe illness, persons diagnosed as having P. falciparum infection are at risk for developing severe life-threatening complications. Health-care workers are encouraged to consult appropriate sources for malaria treatment recommendations or call CDC's National Center for Infectious Diseases, Division of Parasitic Diseases at (770) 488-7760. Detailed recommendations for preventing malaria are available 24 hours a day by telephone ({404} 332-4555) or facsimile ({404} 332-4565) from the CDC Malaria Hotline. In addition, CDC annually publishes updated recommendations in the Health Information for International Travel (5), which is available through the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402-9235; telephone (202) 783-3238. Acknowledgments The authors thank the following persons and organizations for providing information described in this surveillance summary: State and local health departments. Personnel of the preventive medicine services of the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Army, and the U.S. Navy. J.R. Aquirre, Long Beach Department of Health; R.R. Roberto, M.D., Disease Control Section, California Department of Health Services; P. Vaernet, R.N., California Bureau of Disease Control, San Francisco; Valley Medical Center, San Jose, California. E. Bell, R.N., New York City Department of Health; B. Edwards, M.D., Queens Hospital Center, Jamaica, New York. D.A. Waxman, M.D., Wadley Blood Center; S.R. Holms, M.D., Texas Oncology, P.A., Dallas, Texas; K.A. Hendricks, M.D., M.P.H., Texas State Department of Health. C.R. Nichols, M.P.A., Utah Department of Health. References

Table_1 Note: To print large tables and graphs users may have to change their printer settings to landscape and use a small font size.

TABLE 1. Number of malaria cases * in US and foreign civilians and U.S.

military personnel -- United States, 1966-1992

============================================================================

U.S. military U.S. Foreign

Year personnel civilians civilians Unknown Total

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

1966 621 89 32 22 764

1967 2,699 92 51 15 2,857

1968 2,567 82 49 0 2,698

1969 3,914 90 47 11 4,062

1970 4,096 90 44 17 4,247

1971 2,975 79 69 57 3,180

1972 454 106 54 0 614

1973 41 103 78 0 222

1974 21 158 144 0 323

1975 17 199 232 0 448

1976 5 178 227 5 415

1977 11 233 237 0 481

1978 31 270 315 0 616

1979 11 229 634 3 877

1980 26 303 1,534 1 1,864

1981 21 273 809 0 1,103

1982 8 348 574 0 930

1983 10 325 468 0 803

1984 24 360 632 0 1,016

1985 31 446 568 0 1,045

1986 35 410 646 0 1,091

1987 23 421 488 0 932

1988 33 550 440 0 1,023

1989 35 591 476 0 1,102

1990 36 558 504 0 1,098

1991 22 585 439 0 1,046

1992 29 394 481 6 910

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

* A case was defined as symptomatic or asymptomatic illness that occurs in

the United States in a person who has microscopically confirmed malaria

parasitemia, regardless of whether the person had previous attacks of

malaria while in other countries. A subsequent attack of malaria occurring

in a person is counted as an additional case if the demonstrated

Plasmodium species differs from the initially identified species. A

subsequent attack of malaria occurring in a person while in the United

States could indicate a relapsing infection or treatment failure resulting

from drug resistance if the demonstrated Plasmodium species is the same

species identified previously.

============================================================================

Return to top. Figure_1  Return to top. Table_2 Note: To print large tables and graphs users may have to change their printer settings to landscape and use a small font size.

TABLE 2. Number of malaria cases, by Plasmodium species -- United States,

1991 and 1992

=========================================================================

1991 1992

Plasmodium -------------- ---------------

species No. (%) No. (%)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

P. vivax 453 ( 43.3) 463 ( 50.9)

P. falciparum 410 ( 39.2) 296 ( 32.5)

P. malariae 62 ( 5.9) 39 ( 4.3)

P. ovale 24 ( 2.3) 28 ( 3.1)

Undetermined 97 ( 9.3) 84 ( 9.2)

Total 1,046 (100.0) 910 (100.0)

=========================================================================

Return to top. Figure_2  Return to top. Table_3 Note: To print large tables and graphs users may have to change their printer settings to landscape and use a small font size. TABLE 3. Number of malaria cases, by Plasmodium species and area of acquisition -- United States, 1992 ========================================================================================================== Area of Plasmodium species acquisition P. vivax P. falciparum P. malariae P. ovale Mixed Unknown Total ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- AFRICA 38 221 15 27 0 36 337 Algeria 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 Angola 0 4 0 0 0 0 4 Benin 1 1 0 0 0 0 2 Burkina Faso 0 2 0 0 0 0 2 Cameroon 0 11 0 0 0 0 11 Central African Republic 1 1 0 0 0 0 2 Chad 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 Djibouti 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 Egypt 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Equatorial Guinea 0 1 0 0 0 1 2 Ethiopia 1 1 0 0 0 0 2 Gambia 1 1 0 0 0 0 2 Ghana 3 14 2 1 0 1 21 Guinea 0 2 0 0 0 0 2 Ivory Coast 1 9 0 0 0 0 10 Kenya 5 12 4 2 0 4 27 Liberia 0 12 3 3 0 2 20 Madagascar 1 2 0 0 0 0 3 Malawi 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 Mali 0 4 0 1 0 0 5 Mauritania 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Niger 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 Nigeria 6 88 3 6 0 10 113 Rwanda 1 0 0 1 0 0 2 Senegal 0 1 0 1 0 0 2 Sierra Leone 0 11 0 3 0 3 17 South Africa 0 1 0 0 0 1 2 Tanzania 0 3 0 0 0 1 4 Togo 0 2 0 2 0 0 4 Uganda 0 6 0 2 0 0 8 Zaire 1 1 0 1 0 0 3 Zambia 0 3 1 0 0 0 4 Zimbabwe 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 Africa, Central * 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Africa, East * 7 5 1 2 0 1 16 Africa, South * 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Africa, West * 0 9 0 0 0 1 10 Africa, Unspecified * 5 9 1 2 0 9 26 ASIA 242 50 10 0 0 28 330 Afghanistan 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 Cambodia 32 17 1 0 0 11 61 China 2 2 0 0 0 1 5 India 127 15 6 0 0 9 157 Indonesia 12 2 0 0 0 1 15 Laos 4 0 0 0 0 0 4 Malaysia 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 Middle East, Unspecified 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 Myanmar (Burma) 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Pakistan 16 4 0 0 0 1 21 Philippines 7 3 0 0 0 0 10 Sri Lanka 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Thailand 4 0 0 0 0 0 4 Vietnam 17 3 2 0 0 2 24 Yemen 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 Asia, Southeast * 11 1 1 0 0 1 14 Asia, Unspecified * 8 1 0 0 0 0 9 CENTRAL AMERICA AND CARIBBEAN 114 11 8 0 0 6 139 Belize 3 0 0 0 0 0 3 Costa Rica 5 0 1 0 0 0 6 El Salvador 11 0 2 0 0 0 13 Guatemala 21 1 3 0 0 1 26 Haiti 0 7 0 0 0 1 8 Honduras 45 1 1 0 0 2 49 Nicaragua 4 0 1 0 0 1 6 Panama 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Central America, Unspecified * 24 2 0 0 0 1 27 NORTH AMERICA 20 3 2 0 0 5 30 Mexico 17 1 0 0 0 5 23 United States 3 2 2 0 0 0 7 SOUTH AMERICA 8 4 0 0 0 2 14 Brazil 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Colombia 1 1 0 0 0 0 2 Ecuador 1 2 0 0 0 0 3 French Guiana 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Guyana 1 0 0 0 0 1 2 Venezuela 1 0 0 0 0 1 2 South America, Unspecified * 2 1 0 0 0 0 3 OCEANIA 27 4 3 0 0 2 36 Papua New Guinea 16 3 2 0 0 2 23 Solomon Islands 6 0 1 0 0 0 7 Vanuatu 2 0 0 0 0 0 2 Oceania, Unspecified * 3 1 0 0 0 0 4 Unknown 14 3 1 1 0 5 24 Total 463 296 39 28 0 84 910 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- * Country unspecified. ========================================================================================================== Return to top. Table_4 Note: To print large tables and graphs users may have to change their printer settings to landscape and use a small font size.

TABLE 4. Number of imported malaria cases, by Plasmodium species and by interval

between date of arrival in the country and onset of illness -- United States, 1992

===================================================================================

Plasmodium species

-------------------------------------------------

P. vivax P. falciparum P. malarie P. ovale Total

Interval ----------- -------------- ---------- --------- ---------

(mos) No. (%) No. (%) No. (%) No. (%) No. (%)

<1 100 ( 31.6) 175( 88.4) 10 ( 50.0) 1( 5.0) 286( 51.6)

1-2 58 ( 18.4) 13( 6.6) 3 ( 15.0) 6( 30.0) 80( 14.4)

3-5 74 ( 23.4) 7( 3.5) 3 ( 15.0) 2( 10.0) 86( 15.5)

6-12 72 ( 22.8) 2( 1.0) 4 ( 20.0) 8( 40.0) 86( 15.5)

>=13 12 ( 3.8) 1( 0.5) 0 ( 0.0) 3( 15.0) 16( 2.9)

Total 316 (100.0 ) 198(100.0) 20 (100.0) 20(100.0) 554(100.0)

===================================================================================

Return to top. Table_5 Note: To print large tables and graphs users may have to change their printer settings to landscape and use a small font size.

TABLE 5. Number of imported malaria cases U.S. and foreign civilians, by area

of acquisition -- United States, 1992

==============================================================================

U.S. civilians Foreign civilians Total

Area of -------------- ----------------- ---------------

acquisition No. (%) No. (%) No. (%)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Africa 190 ( 49.1) 142 ( 29.5) 332 ( 38.3)

Asia 89 ( 23.0) 233 ( 48.4) 322 ( 37.1)

Caribbean 2 ( 0.5) 6 ( 1.3) 8 ( 0.9)

Central America 50 ( 12.9) 62 ( 12.9) 112 ( 12.9)

Mexico 4 ( 1.0) 19 ( 4.0) 23 ( 2.7)

Oceania 33 ( 8.5) 3 ( 0.6) 36 ( 4.1)

South America 11 ( 2.8) 3 ( 0.6) 14 ( 1.6)

Unknown 8 ( 2.1) 13 ( 2.7) 21 ( 2.4)

Total 387 (100.0) 481 (100.0) 868 (100.0)

==============================================================================

Return to top. Table_6 Note: To print large tables and graphs users may have to change their printer settings to landscape and use a small font size.

TABLE 6. Number of imported malaria cases in U.S. civilians,

by purpose of travel at the time of acquisition -- United

States, 1992

=============================================================

Imported cases

-----------------

Category No. (%)

-------------------------------------------------------------

Business representative 42 ( 10.9)

Government employee 7 ( 1.8)

Missionary 41 ( 10.6)

Peace Corps worker 16 ( 4.1)

Seaman/Aircrew 2 ( 0.5)

Teacher/Student 44 ( 11.4)

Tourist 41 ( 10.6)

Visiting a friend or relative 55 ( 14.2)

Other 30 ( 7.8)

Unknown 109 ( 28.2)

Total 387 (100.0)

=============================================================

Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 09/19/98 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|