|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

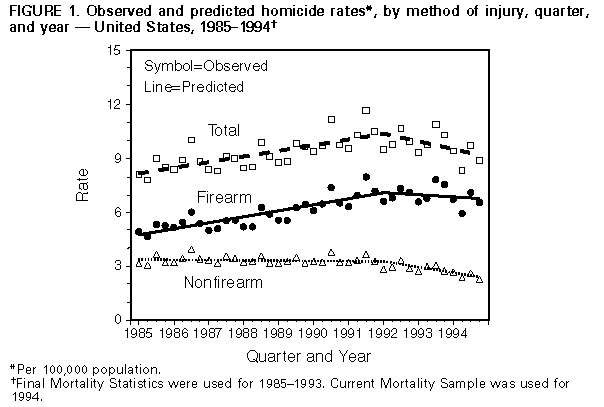

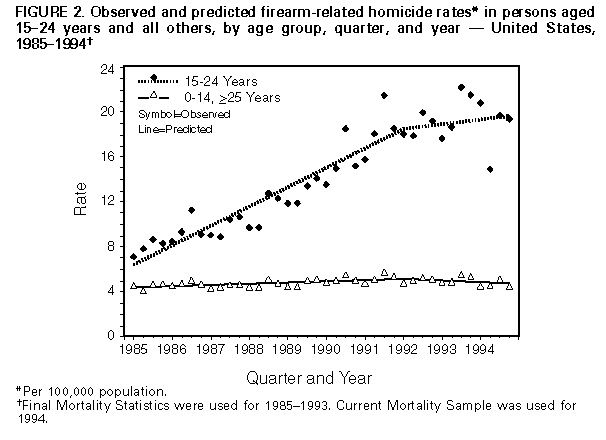

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Trends in Rates of Homicide -- United States, 1985-1994During 1993, a total of 26,009 homicides were reported in the United States; 71% were firearm-related, and one third of all homicides occurred among persons aged 15-24 years (1). Since 1985, national homicide rates have increased sharply, especially firearm-related homicides and homicides among persons aged 15-24 years. However, based on data from the Supplementary Homicide Report compiled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and reports from some cities, homicide rates have been stable or declining since 1993. To examine this trend and to assess the relative contributions of firearm- and nonfirearm-related homicide to these recent changes, CDC analyzed national vital statistics data for 1985-1994. This report summarizes this analysis, which indicates that overall rates of homicide increased from 1985 to 1991 and decreased from 1992 to 1994, and that during these two periods, rates for total firearm-related homicides and homicide among persons aged 15-24 years increased then stabilized but remained at record-high levels. Data for 1985-1993 (the most recent year for which complete data are available) were from final mortality statistics (FMS), and data for 1994 were from the Current Mortality Sample (CMS). FMS are based on information from death certificates submitted by all 50 states and the District of Columbia, and CMS data provide national estimates based on a 10% systematic sample of death certificates received monthly by the vital statistics offices in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and New York City. A homicide was defined as death resulting from injury purposefully inflicted by another person (including those caused by law enforcement officers or legal intervention), for which the underlying cause listed on the death certificate was International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), codes E960-E978. Population estimates are based on data from the Bureau of the Census (2). Trends for both firearm- and nonfirearm-related homicides for all ages and for persons aged 15-24 years were reviewed. To assess the accuracy with which the CMS data reflect final statistics, 1993 CMS and FMS homicide rates were compared. During sequential quarters of 1993, compared with FMS quarterly homicide rates, CMS rates differed by -0.4%, -4.6%, +1.2% and -4.6%, indicating the accuracy of weighted CMS rates for estimating final homicide rates. Quarterly homicide rates were analyzed using piecewise regression models to account for the observed changes in linear relations over time. Three time periods (1985-1987, 1988-1991, and 1992-1994) were selected for analysis based on a preliminary review of scatter plots of observed rates and their apparent changes in slopes. Statistical testing was conducted to determine whether the slope of the predicted values of the regression line (i.e., predicted rates) changed over each of these time periods. Statistical testing for a discontinuous piecewise regression model also was conducted to determine whether the rate changed significantly at the beginning of each new time period (i.e., "jump point"). No significant jump points were observed, and analyses consistently indicated that the slope of the regression line for 1985-1987 was similar to that for 1988-1991. Therefore, regression lines are presented only for two periods: 1985-1991 and 1992-1994. Overall results and interpretation of the piecewise model using two pieces are no different from those using a model with three pieces. During 1985-1991, the overall rate of homicide in the United States increased significantly (p less than 0.01) (slope=less than 0.1, 4% annually); during 1992-1994, the rate decreased significantly (p less than 0.01) (slope=-0.1, 1% annually) (Figure_1). During 1985-1991, nonfirearm-related homicide rates remained stable, and firearm-related homicide rates increased significantly (p less than 0.01). During 1992-1994, nonfirearm-related homicide rates declined significantly (p less than 0.01), and firearm-related homicide rates stabilized. During 1985-1991, the rate of total homicide increased significantly for persons aged 15-24 years (p less than 0.01) (slope=0.4, 16% annually). Firearm-related homicide rates for this age group also increased during 1985-1991 (p less than 0.01) (slope=0.4, 23% annually) (Figure_2), with most of the increase occurring during 1988-1991. During 1992-1994, the rates of total and firearm-related homicide were stable. For all other age groups, the trend in firearm-related homicide rates followed a similar pattern, with significant increases during 1985-1991 (p less than 0.01) and stable rates during 1992-1994 (Figure_2). Nonfirearm-related homicide rates for persons aged 15-24 years and all other ages were lower than firearm-related homicide rates and were stable during 1985-1991 and decreased significantly during 1992-1994 (p less than 0.01). Analysis of firearm-related homicide rates by sex for persons aged 15-24 years indicates that rates for males and females reflected the overall trend for this age group. Rates for females were substantially lower than those for males. For both sexes, rates increased significantly during 1985-1991 (p less than 0.01) and stabilized during 1992-1994. Reported by: Div of Violence Prevention, Office of Statistics and Programming, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Div of Vital Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC. Editorial NoteEditorial Note: The findings in this report confirm that the overall homicide rate increased rapidly during the late 1980s and began to decline in 1992; in addition, nonfirearm-related homicide rates decreased, and the percentage of firearm-related homicides increased. During 1985-1994, the percentage of firearm-related homicides among all homicides in the total population increased from 60% to 72% and among persons aged 15-24 years, from 67% to 87% (3). These increases illustrate that changes in overall homicide rates primarily reflect changes in firearm-related homicides. The stabilization of firearm-related homicide rates during 1992-1994 -- particularly among those aged 15-24 years -- reflects a change from the increasing rates in previous years, even though rates remain at record-high levels. The findings in this report also indicate the usefulness of CMS data as a source of information for monitoring homicide in the United States. Because of the timely availability of CMS data and their accuracy in reflecting final mortality-based homicide rates, these data enable more timely analyses of temporal trends, objective policy formulation, and measurement of progress toward public health goals. The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, because of the small numbers based on CMS data, rates were not examined among age-, race-, and sex-specific subgroups. Second, estimates for some causes of death may be incomplete or skewed because reporting of the underlying cause of death data may not have been complete when the monthly sample was obtained (the data for this potential undercount are adjusted in the annual summary {2}). Strategies for preventing homicide and violence require integration of approaches from multiple disciplines, including criminal justice, education, social services, community advocacy, and public health. For example, public health approaches to prevent violence have focused on 1) changing individual knowledge, skills, and/or attitudes; 2) changing the social and physical environments; and 3) increasing community awareness of the causes and prevention of violence. The public health community also has recognized the influence of social class and poverty on violence. Communities increasingly are adopting programs emphasizing strategies to enhance the skills of youth and parents to reduce violence. These strategies include, for example, 1) school-based curricula that teach coping, communication, and mediation skills (4); 2) family-intervention programs that focus on parental training to positively alter parental practices and family cohesion (5); and 3) preschool efforts to develop intellectual and social skills (6). Because evaluation of prevention strategies is a critical component of public health interventions, CDC is evaluating the effectiveness of selected programs in reducing violent behavior and injury (7). Homicide and assaultive violence now are recognized as global public health problems. Although the U.S. homicide rate ranks higher overall and higher for males aged 15-24 years than those of other highly industrialized countries (8,9), in many less- industrialized countries homicide rates exceed those in the United States (8). To address this global problem, in May 1996 the 190 nations of the World Health Organization (WHO) passed a resolution declaring violence a worldwide public health problem, urging member states to assess the public health impact of violence, and requesting the Director-General of WHO to initiate a science-based public health approach to violence prevention. This resolution provides a scientific framework for action throughout the world addressing global violence. References

Figure_1  Return to top. Figure_2  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 09/19/98 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|