|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

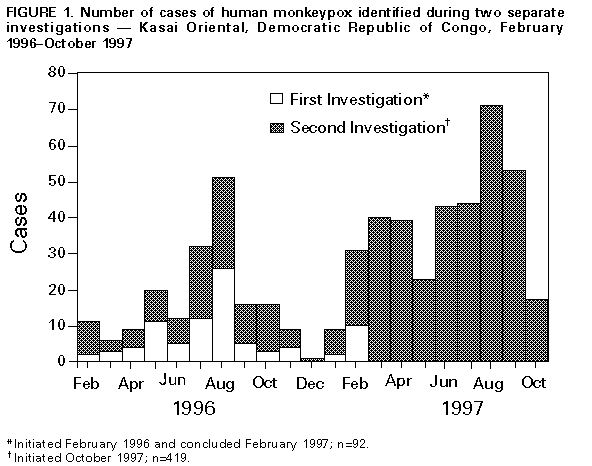

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Human Monkeypox -- Kasai Oriental, Democratic Republic of Congo, February 1996-October 1997Human monkeypox is a severe smallpox-like illness caused by monkeypox virus (MPV); monkeypox occurs in sporadic outbreaks, and infection is enzootic among squirrels and monkeys in the rainforests of western and central Africa (1). In 1996, cases of monkeypox were reported from villages in the Katako-Kombe Health Zone, Kasai Oriental, Zaire (i.e., Democratic Republic of Congo) (2,3). The World Health Organization (WHO), in collaboration with CDC, investigated this outbreak and identified 92 suspected cases with onset during February 1996-February 1997, and isolated MPV from lesions of active cases (4). Cases continued to be reported, and a new investigation was initiated by WHO and CDC in October 1997. This report summarizes the results of the field investigation, which indicate that this is the largest human monkeypox outbreak ever recorded. In October 1997, active case ascertainment was conducted in the Katako-Kombe and Lodja health-care zones, Kasai Oriental, Democratic Republic of Congo. A probable case of monkeypox was defined as the occurrence since February 1996 of fever, a vesicular-pustular rash similar to that depicted in a WHO reference photo, or five or more facial pock marks in a resident of Kasai Oriental. A possible case was defined as a history of fever and vesicular or crusty rash in a resident of Kasai Oriental. A primary case was defined as monkeypox in a person who reported no contact with another person with monkeypox; a secondary case was defined as monkeypox in a person who had contact with a person with monkeypox 7-21 days before onset of disease. Serum was collected from approximately 300 case-patients and crusted scabs or vesicular fluid from 19 case-patients with active disease. Data and specimens are being analyzed. In the current investigation, 419 cases have been identified: 344 in the Katako-Kombe Health Zone (attack rate {AR}=1.1 per 1000 population) and 75 in the Lodja Health Zone (AR=0.3). Of these, 304 (73%) met the probable case definition, and 115 (27%) were considered possible monkeypox cases. Most (85%) cases occurred in persons aged less than 16 years. Nineteen persons had active disease. Preliminary testing of lesional material identified MPV in nine cases and varicella zoster virus in four. Of the 344 cases in the Katako-Kombe Health Zone, five persons died (case fatality ratio: 1.5%) within 3 weeks of rash onset; decedents ranged in age from 4 to 8 years. All 339 surviving case-patients were examined and interviewed. Of these, 183 (54%) had been confined to bed rest for 3-10 days. Twenty (6%) case-patients had scar evidence of vaccinia vaccination, and 19 reported a past history of chickenpox. Other reported manifestations included cervical lymphadenopathy (69%), sore throat (63%), mouth ulcers (50%), cough (41%), and diarrhea (11%). Since February 1996, a total of 511 human monkeypox cases have been identified in the Katako-Kombe and Lodja health zones. Onsets of illness peaked in August 1996 and August 1997 (Figure_1). Case-patients resided in 54 villages in Katako-Kombe and 24 in Lodja. The highest AR (113) occurred in Akungula (1997 population: 399), the epicenter of the outbreak in August 1996. The largest number of cases occurred in the adjacent village of Ekanga (54 cases clustered in 13 housing compounds) (AR=43). Cases increased substantially in Ekanga and the two nearby villages of Ombeka (21 cases; AR=22) and Dimanga (seven cases; AR=20) in March 1997. The peak in August 1997 primarily represented case-patients who resided in other villages. Of the 419 cases identified during the investigation initiated in October 1997, 94 (22%) were primary, and the remainder were secondary; 147 (35%) reported having traveled outside their home village during the 3 weeks preceding disease onset. Of the secondary cases, 53% reported having had antecedent contact with another case-patient in the neighborhood, 48% in the housing compound, and 42% in an individual household. Primary cases with no apparent association with the clusters in the Akungula/Ekanga occurred in 49 of the 78 affected villages. Reported by: A Aplogan, MD, V Mangindula, PT Muamba, MD, GN Mwema, PhD, L Okito, MD, RG Pebody, MBChB, CE Roth, MBBChir, LS Shongo, M Szczeniowski, KF Tshioko, MD, Monkeypox Investigation Team. Epicentre, Paris, France. Institut National de Recherche Biomedicale; School of Public Health, Univ of Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. European Program for Intervention Epidemiology Training, Brussels, Belgium. Public Health Laboratory Svc, England and Wales. Emerging and Other Communicable Diseases Surveillance and Control, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Viral Examthems and Herpesvirus Br, Div of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC. Editorial NoteEditorial Note: This report describes the largest recorded outbreak of human monkeypox. Human-to-human transmission has continued for 2 years with peaks each August, and cases have occurred throughout large areas of the Katako-Kombe and Lodja health-care zones. The large number of cases in this outbreak may reflect an increase in the number of susceptible persons as a result of the cessation of smallpox vaccination, which is highly effective for preventing monkeypox, or changes in other factors related to MPV transmission. Clinical disease in this outbreak was milder than in previous outbreaks, when case fatality was approximately 10% (1). In this outbreak, secondary ARs were estimated to be 8% (95% confidence interval= 5%-12%), which is similar to secondary ARs estimated during monkeypox surveillance in Zaire during the early 1980s (4%-12%) (1). Transmission has ceased at the epicenter of this outbreak and surrounding villages. The more recently detected cases have occurred in geographically distant clusters; most of these cases have not been obviously associated with cases in the epicenter. These recent cases may instead have resulted from independent introductions of the virus into the human population through animal contact. Ongoing surveillance is essential to monitor the outbreak and secondary ARs, clarify primary and secondary transmission mechanisms, and consider intervention strategies. If human monkeypox transmission is sustained without introduction from reservoir animals, vaccinia vaccination (5) targeted to the appropriate population may be considered. References

Figure_1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 09/19/98 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|