|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

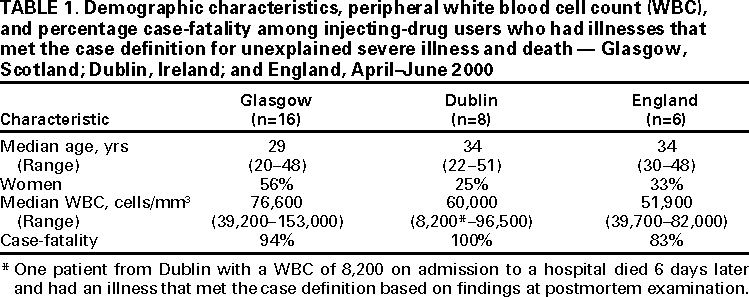

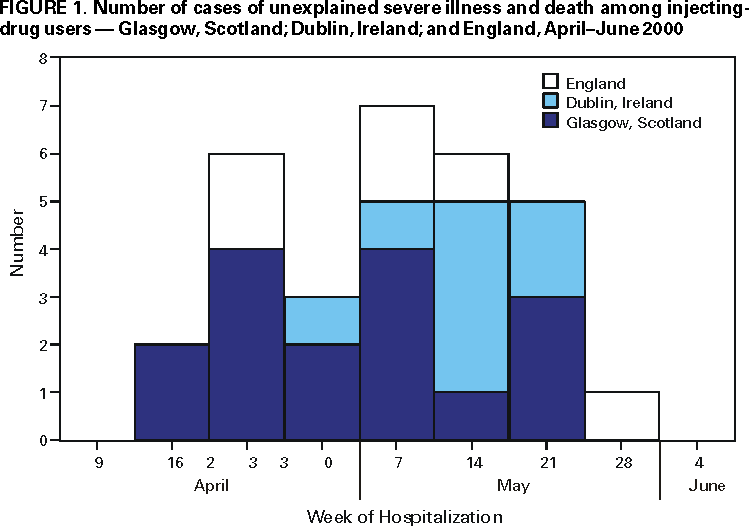

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Unexplained Illness and Death Among Injecting-Drug Users --- Glasgow, Scotland; Dublin, Ireland; and England, April--June 2000Since April 19, 2000, 30 injecting-drug users (IDUs) died or were hospitalized with unexplained severe illness in Glasgow, Scotland. Illness was characterized by extensive local inflammation at a subcutaneous or intramuscular injection site often followed by hypotension and circulatory collapse. Since April 24, 2000, 15 IDUs in Dublin, Ireland, and 14 IDUs in England with similar illnesses have been identified. Despite debridement and broad spectrum antibiotics, 30 (51%) of the 59 patients in all three countries have died. This report further describes the clinical syndrome and key epidemiologic features of the illness as characterized by a preliminary investigation by health authorities in Scotland, Ireland, England, and the United States (1). A case of unexplained illness was defined as soft tissue inflammation (i.e., abscess, cellulitis, fasciitis, or myositis) at an injection site, and either 1) severe systemic toxicity (i.e., sustained systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg despite fluid resuscitation and total peripheral white blood cell count [WBC] >30,000 cells/mm3), or 2) postmortem evidence of a diffuse toxic or infectious process including pleural effusions and soft tissue edema or necrosis, in an IDU admitted to a hospital or found dead since April 1, 2000. As of June 5, in Glasgow, 16 (53%) of 30 IDUs evaluated had illnesses that met the case definition (Figure 1). In Dublin, eight (53%) of 15 IDUs, and in England, six (42%) of 14 IDUs had illnesses that met the case definition (Figure 1). Demographic information, peripheral WBC, and case-fatality among IDUs were similar in all three countries (Table 1). Most cases had progressive symptoms with a median of 3 days (range: 0--14 days) between illness onset and hospitalization. Among persons who died while hospitalized, the median time from admission to death was 2 days (range: 0--13 days). Pleural effusion and extensive edema at an injection site were prominent features at postmortem examination. Cultures of blood and tissue yielded multiple organisms from several patients including group A streptococcus, Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium species, and Bacillus species. However, the variable and polymicrobial results and potential postmortem contamination complicate the interpretation of these findings and fail to reveal a definitive etiologic agent. Clinical and drug specimens are being evaluated at CDC, the Public Health Laboratory Service in England, and local laboratories in Glasgow and Dublin. Culture, serologic, molecular, immunopathologic, and histopathologic evaluation of blood and tissue from case-patients have revealed no evidence of Bacillus anthracis. B. anthracis was isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid of an IDU residing in Oslo, Norway, hospitalized in early April 2000 with a localized abscess, elevated WBC (45,000 cells/mm3), and hemorrhagic meningitis resulting in death (2). Investigations continue to characterize further the 29 reported unexplained illnesses among IDUs whose illnesses failed to meet the case definition but may be linked to this outbreak. Surveillance activities have been initiated in all hospitals in Scotland, Ireland, England, and Wales to identify additional cases. Information regarding these illnesses is being disseminated to medical practitioners and IDUs, and a case-control study is under way to identify risk factors for disease and to develop prevention strategies. As of June 5, no similar illnesses have been reported in the United States to CDC through the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Reported by: S Ahmed, MD, L Gruer, MD, C McGuigan, MD, G Penrice, MD, K Roberts, MPhil, Dept of Public Health, Greater Glasgow Health Board; J Hood, MD, Dept of Microbiology, Glasgow Royal Infirmary; P Redding, MD, Dept of Microbiology, Victoria Infirmary Glasgow; G Edwards, MD, Stobhill General Hospital; C Farris, MD, Dept of Clinical Microbiology, Glasgow Western Infirmary; D Cromie, MD, Dept of Public Health, Lanarkshire Health Board; H Howie, MD, Dept of Public Health, Grampian Health Board; A Leonard, MD, Dept of Microbiology, Monklands Hospital; D Goldberg, MD, A Taylor, PhD, S Hutchinson, MSc, S Wadd, PhD, R Andraghetti, MD, Scottish Centre for Infection and Environmental Health, Glasgow, Scotland. J Barry, MD, G Sayers, MD, M Cronin, MD, T O'Connell, MD, M Ward, MD, P O'Sullivan, MD, B O'Herlihy, MD, Eastern Regional Health Authority, Dept of Public Health; E Keenan, MD, J O'Connor, MD, L Mullen, MSc, B Sweeney, MD, Eastern Regional Health Authority Area Health Boards' Drug Svcs; D O'Flanagan, MD, D Igoe, MD, National Disease Surveillance Centre; C Bergin, MD, S O'Briain, MD, C Keane, MD, E Mulvihill, MD, P Plunkett, MD, G McMahon, MD, T Boyle, MD, S Clarke, MD, St. James's Hospital; E Leen, MD, James Connolly Memorial Hospital; M Cassidy, MD, State Pathology Svc, Dublin, Ireland. T Djuretic, MD, N Gill, MD, V Hope, PhD, J Jones, MD, G Nichols, PhD, A Weild, MPhil, Public Health Laboratory Svc (PHLS) Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre; R George, MD, PHLS Respiratory and Systemic Infection Laboratory; P Borriello, PhD, PHLS Central Public Health Laboratory, London, England; J Brazier, PhD, J Salmon, MD, PHLS Anaerobe Reference Unit, Cardiff, Wales; N Lightfoot, MD, PHLS North, Newcastle; A Roberts, PhD, Centre for Applied Microbiology and Research, Porton Down, England. Infectious Diseases Pathology Activity, Div of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases; Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Program; Meningitis and Special Pathogens Br, Div of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases; and EIS officers, CDC. Editorial Note:The localized inflammatory process affecting skin or muscle combined with systemic toxicity characterized by a leukemoid reaction suggests the role of a toxin-mediated cause of illness among IDUs in Scotland, Ireland, and England. Despite extensive microbiologic evaluation for several of these cases, no specific causative pathogen has been identified. Although the initial symptoms of anthrax can be nondescript before the onset of circulatory collapse and death (3), the absence of B. anthracis bacteremia or histologic or molecular evidence for B. anthracis suggests that anthrax-associated toxemia is not a cause of illness among these IDUs. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome and staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome are both characterized by the sudden onset of shock and organ failure, often associated with skin and soft tissue damage (4,5). However, most cases in Scotland, Ireland, and England have not had group A streptococcus isolated (a required feature of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome), and none developed a rash or desquamation of the palms and soles (diagnostic criteria of staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome). Fastidious, anaerobic bacteria, such as Clostridium species, have caused a distinctive, toxin-mediated, often fatal infection characterized by sudden onset of shock with unrelenting hypotension, myonecrosis, generalized tissue edema, and a profound leukemoid reaction in the absence of high fever and rash (6)---a clinical course resembling that seen among cases in Scotland, Ireland, and England. Laboratory procedures have been enhanced for the identification of anaerobic bacteria and noninfectious toxins. The emergence of a new illness among IDUs is possible because the injection of nonsterilized drugs into skin and soft tissue can provide a suitable environment for contaminating pathogens and their toxins or noninfectious toxins alone. Up to 32% of IDUs, particularly those who inject drugs subcutaneously or intramuscularly, have soft tissue abscesses or cellulitis at any given time (7,8). Unusual infections have been linked to subcutaneous or intramuscular drug use, including tetanus and wound botulism among heroin and black tar heroin users, respectively, in California (9,10), and group A streptococcal infections among cocaine users in Switzerland (11). Microbial or chemical contamination can occur at one of many steps, including production, mixing, dilution, or preparation of the drugs or at the time of injection through contaminated paraphernalia or skin. Because the source of contamination remains unknown and may be common in these countries, this investigation highlights the importance of enhanced surveillance for syndrome-based illness across national boundaries. Health-care providers and public health personnel are encouraged to report persons with illnesses meeting the case definition to their designated public health authorities. References

Table 1  Return to top. Figure 1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 6/8/2000 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|