|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

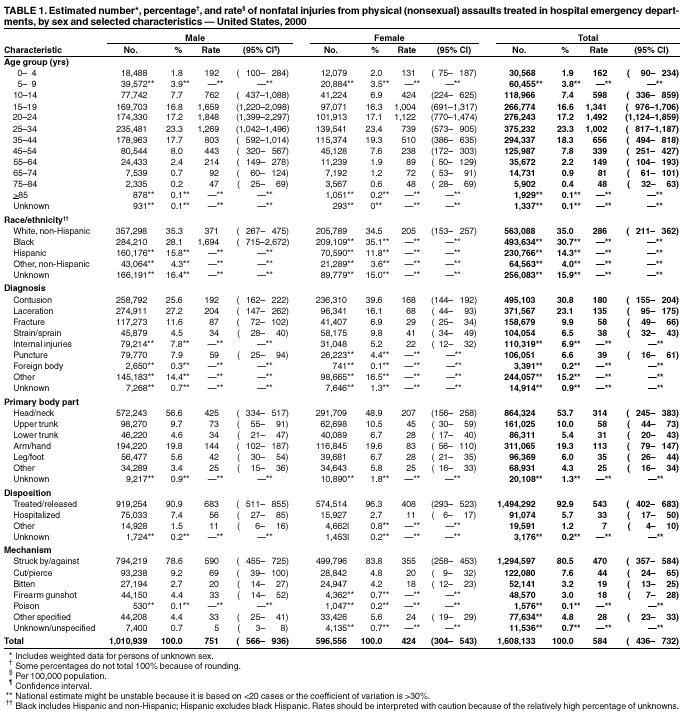

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Nonfatal Physical Assault--Related Injuries Treated in Hospital Emergency Departments ---United States, 2000CDC, in collaboration with the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), expanded CPSC's National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) in July 2000 to include all types and external causes of nonfatal injuries treated in U.S. hospital emergency departments (EDs). This ongoing surveillance system, called NEISS All Injury Program (NEISS-AIP), can be used to calculate national, annualized, weighted estimates for nonfatal injuries treated in U.S. hospital EDs. This report summarizes NEISS-AIP data, which indicate that approximately 1.6 million persons were treated in U.S. EDs during 2000 for nonfatal physical (i.e., nonsexual) assault--related injuries. Such injuries occurred disproportionately among males, adolescents, and young adults, particularly among black males; most of these injuries were contusions or lacerations, few of which resulted in hospital admission. NEISS-AIP data can increase understanding of physical assault--related injuries and serve as a basis for monitoring trends, facilitating additional research, and evaluating intervention approaches. NEISS-AIP includes data from 66 (out of the 100) NEISS hospitals, which are a nationally representative, stratified probability sample of all hospitals in the United States and its territories with a minimum of six beds and a 24-hour ED (1,2). NEISS-AIP provides data on approximately 500,000 injury- and consumer product--related ED cases each year. Data from these cases are weighted by the inverse of the probability of selection to provide national estimates (1). Annualized estimates for this report are based on weighted data for 13,976 nonfatal assault-related injuries treated in EDs during July--December 2000. The weight of each case was doubled, and then these adjusted values were added to provide annualized estimates for the overall population and population subgroups (i.e., age, sex, and race/ethnicity*). A direct variance estimation procedure was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals and to account for the complex sample design (1). Injuries were defined as bodily harm resulting from acute exposure to an external force or substance, including unintentional and violence-related causes. Cases were excluded from this analysis if 1) the principal diagnosis was an illness, pain only, psychological harm (e.g., anxiety and depression) only, contact dermatitis associated with exposure to consumer products (e.g., body lotions, detergents, and diapers) and plants (e.g., poison ivy), or unknown; or 2) the ED visit was for adverse effects of therapeutic drugs or of surgical and medical care (3). All injuries were classified according to the intent (i.e., unintentional, sexual and physical assault, self-harm, and legal intervention†) of the most severe injury (4). Suspected and confirmed instances of interpersonal violence were coded as assaults; persons injured included victims, bystanders, police, and perpetrators. Data also were collected about injury diagnosis, primary body part injured, disposition, and mechanism. The mechanism of injury is the precipitating mechanism (e.g., struck by/against, cut/pierced, or bitten) that initiated the chain of events leading to the injury, similar to the underlying cause of an injury-related death. Mechanisms of injury were classified into recommended major external cause-of-injury groupings (3,5) according to definitions consistent with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modifications (ICD-9-CM) external-cause coding guidelines (6). During 2000, an estimated 1,021,118 males and 650,361 females were treated in EDs for injuries resulting from nonfatal assaults, including an estimated 63,984 sexual assaults. Although sexual assaults accounted for a small proportion (females: 8%, males: 1%) of all assault-related injuries, the rate of ED visits for sexual assault--related injuries was five times higher for females (38.2 per 100,000 population) than for males (7.6). Because the number of sexual assaults during the period studied was too low to permit reliable estimates by victim and injury characteristics, this report focuses only on nonfatal injuries resulting from nonsexual assaults (i.e., nonfatal physical assault--related injuries). NEISS-AIP data on nonfatal physical assault--related injuries were analyzed by sex, age, race/ethnicity, mechanism of injury, diagnosis, primary body part injured, and disposition. The physical assault rate was approximately 77% higher for males than for females (Table 1). Males and females aged 20--24 years had the highest injury rates per 100,000 persons (1,848 and 1,122, respectively) among all age groups; the rate for black males was approximately 4.6 times higher than the rate for non-Hispanic white males. Most (81%) physical assault--related injuries were caused by a person being struck by another person, either with an object or a personal weapon (e.g., fist or foot). Fewer injuries resulted from being cut or pierced with a sharp instrument (8%) or from gunshots (3%). Although males had higher rates of being struck or injured with a sharp instrument than females, the rate of being bitten was comparable for males and females. Most injuries were diagnosed as contusions (31%) or lacerations (23%), followed by fractures (10%), internal injuries (7%), punctures (7%), and strains or sprains (7%). The parts of the body affected most were the head (54%), arms/hands (19%), and upper trunk (10%). Most (93%) patients were treated and released, and 6% required hospitalization; the hospitalization rate was approximately five times higher for males than for females. To estimate variations in the lethality of physical assaults by sex and injury mechanism, CDC compared the 2000 NEISS-AIP data with 1999 homicide data from the National Vital Statistics System, which includes information from all death certificates filed in the 50 states and the District of Columbia (7). The ratio of nonfatal injuries to homicides was 94:1, and the ratio of firearm-related injuries from nonfatal physical assaults to firearm-related homicides was 4:1. The ratios of nonfatal to fatal injuries were substantially higher for injuries in which a person was cut or pierced with a sharp instrument (64:1) or struck by/against (3,143:1). Although men were far more likely to be assaulted or killed than women, the ratio of nonfatal injuries to homicides was higher for females (144:1) than for males (78:1). Reported by: TR Simon, PhD, LE Saltzman, PhD, MH Swahn, PhD, JA Mercy, PhD, EM Ingram, PhD, RR Mahendra, MPH, Div of Violence Prevention; JL Annest, PhD, P Holmgreen, MS, Office of Statistics and Programming, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC. Editorial Note:In 2000, an estimated 1,608,133 persons were treated for nonfatal physical assault--related injuries in U.S. EDs. The NEISS-AIP results and the ratios of physical assault--related ED visits to homicides underscore the need to prevent both fatal and nonfatal assault-related injuries. A previous study found that estimates of nonfatal physical assault--related injuries treated in EDs obtained through a supplement to NEISS are approximately 3.2 times higher than the estimated number of ED visits based on reports by crime victims interviewed in the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) (8). The NCVS estimate of the number of ED visits might be lower because of victim reluctance to report injuries as crime-related and difficulty in securing a sample that adequately represents those at greatest risk for violent victimization (8,9). Although NCVS includes fewer assault-related injuries treated in EDs, NCVS data indicate that most (82%) injured victims of physical assaults were not treated in an ED or hospital (10). NCVS provides estimates of all physical assault--related injuries whereas NEISS-AIP data reflect only injuries that were treated in EDs. The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, data were collected for a 6-month period and might not reflect seasonal differences in the number of physical assault--related injuries. Second, NEISS-AIP data are based only on information in ED records and are not linked to or supplemented with other data sources (e.g., police reports). Third, outcomes are specific to ED visits and do not include subsequent outcomes of the injuries. Fourth, NEISS-AIP data reflect only those injuries that were severe enough to require treatment in an ED. Finally, NEISS-AIP data probably provide a conservative estimate of the number of physical assault--related injuries treated in EDs because the violent intent of injury might not be reported. This analysis highlights the value of NEISS-AIP for estimating the number of nonfatal physical assault--related injuries treated in U.S. hospital EDs and for analyzing the characteristics of these injuries. When additional data become available, similar analyses can be generated for sexual assault--related injuries. NEISS-AIP data can help health-care professionals better understand the magnitude and characteristics of physical assault--related injuries and serve as a basis for monitoring trends, facilitating additional research on the costs and consequences of these injuries, and evaluating prevention programs and policies. References

* Often only one entry is available on the ED record for race/ethnicity. The classification scheme for this report assumed that most white Hispanics probably were recorded on the ED record as Hispanics and that most black Hispanics probably were recorded as black. † Injuries inflicted by law enforcement personnel during official duties. Table 1  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 5/30/2002 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/30/2002

|