|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

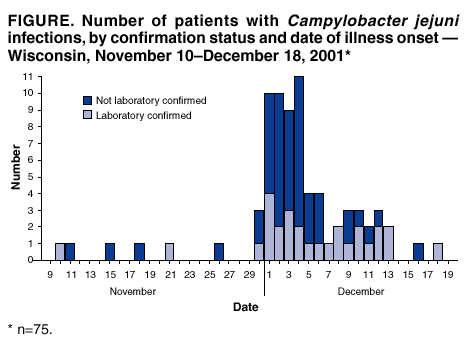

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Outbreak of Campylobacter jejuni Infections Associated with Drinking Unpasteurized Milk Procured through a Cow-Leasing Program --- Wisconsin, 2001On December 7, 2001, the Sawyer County Department of Health and Human Services in northwestern Wisconsin notified the Wisconsin Division of Public Health about five cases of Campylobacter jejuni enteritis. All of the ill persons drank unpasteurized milk obtained at a local dairy farm. This report summarizes the investigation of these and other cases and of a cow-leasing program used to circumvent regulations prohibiting the sale of unpasteurized milk in Wisconsin. The outbreak highlights the hazards of consuming unpasteurized milk and milk products. A case of C. jejuni enteritis was defined as illness in a person from Sawyer County or a surrounding county who had diarrhea or abdominal cramps and fever during November 10--December 18. Case finding was conducted by notifying health-care providers, infection-control practitioners, laboratorians, and the public about the outbreak. A total of 75 persons had illness that met the case definition (Figure). The patients ranged in age from 2 to 63 years (median: 30 years); 41 (56%) were males. Signs and symptoms of illness included diarrhea (93%), abdominal cramps (92%), fever (76%), nausea (40%), and grossly bloody diarrhea (23%). None of the patients was hospitalized, and none had Guillain-Barre syndrome. A total of 70 (93%) patients reported drinking unpasteurized milk from a local dairy farm. Four (5%) patients did not drink unpasteurized milk but were mothers of ill children who drank unpasteurized milk. One patient was a child who attended a child care facility but did not drink unpasteurized milk or have contact with other patients. Of the 75 patients, 29 (39%) provided stool specimens; 28 (97%) specimens grew C. jejuni (Figure). Of the 28 patients with positive stool specimens, 23 (33%) were patients who drank the unpasteurized milk, four were mothers of patients, and one patient had an unknown mode of infection. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed on 21 isolates; the patterns were indistinguishable when restricted separately by two enzymes. The facility that supplied milk to patients was a Grade A organic dairy farm with 36 dairy cows. The farm also had a retail store in which milk and other food products were available. In addition, farm operators provided unpasteurized milk samples at community events and to persons who toured the farm, including children from childcare facilities. Because unpasteurized milk cannot be sold legally to consumers in Wisconsin, the dairy distributed unpasteurized milk through a cow-leasing program. Customers paid an initial fee to lease part of a cow. Farm operators milked the cows and stored the milk from all leased cows together in a bulk tank. Either customers picked up milk at the farm or farm operators had it delivered. On December 8, investigators obtained a milk sample from the farm's bulk milk tank, and cultures of the milk samples grew C. jejuni with a PFGE pattern that matched the outbreak strain. Farm operators were ordered to divert all milk to a processor for pasteurization. State inspectors found the farm to meet Grade A standards for a farm shipping milk to a pasteurization plant. Consumers were advised not to drink unpasteurized milk. To ensure that unpasteurized milk will not be distributed to the public in Wisconsin, state officials are enforcing existing regulations and prohibiting cow-leasing programs. Reported by: P Harrington, Sawyer County Dept of Health and Human Svcs, Hayward; J Archer, MS, JP Davis, MD, State Epidemiologist, Wisconsin Div of Public Health. DR Croft, MD, JK Varma, MD, EIS officers, CDC. Editorial Note:Unpasteurized milk is an important vehicle for transmission of pathogens including Campylobacter spp., Brucella spp., Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (e.g., E. coli O157), Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Salmonella spp. (including multidrug-resistant strains), Mycobacterium bovis, and Listeria monocytogenes (1,2). In 1995, intrastate sale of unpasteurized milk was permitted in 28 states (3). In California, where the sale of unpasteurized milk is legal, 128 (3%) of 3,999 residents reported drinking unpasteurized milk in 1993 (4). Persons who drink unpasteurized milk and milk products might believe that these products taste better, provide greater nutrition than pasteurized products, and/or decrease the risk for various medical conditions (4). However, the benefits of consuming unpasteurized milk and milk products have never been validated scientifically (5). As in this outbreak, in several states milk producers have established cow-leasing programs to circumvent regulations (6). Advocates of unpasteurized milk also have published lists of those states that permit the sale of unpasteurized milk for nonhuman consumption. Persons might use such lists to obtain milk covertly in these states. State regulatory agencies should consider the risk for human illness when reviewing policies regulating the sale of unpasteurized milk. States that permit the sale of unpasteurized milk might consider placing warning labels on such products, as with unpasteurized juice. Because persons might attempt to circumvent existing regulations, further public health research should address how to communicate to consumers the health risks of drinking unpasteurized milk. Acknowledgments This report is based on data contributed by E Simak, J Connell, Sawyer County Dept of Health and Human Svcs, Hayward; T Leitzke, M Barnett, B Carroll, G Hewitt, W Resheske, S Steinhoff, C Koschmann, L Kelly, K Manner, Wisconsin Dept of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection, Madison; T Monson, MS, D Lucas, T Kurzynski, MS, D Hoang-Johnson, L Machmueller, Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene, Madison, Wisconsin. M Beatty, MD, R Tauxe, MD, Div of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC. References

Figure  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 6/27/2002 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 6/27/2002

|