|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

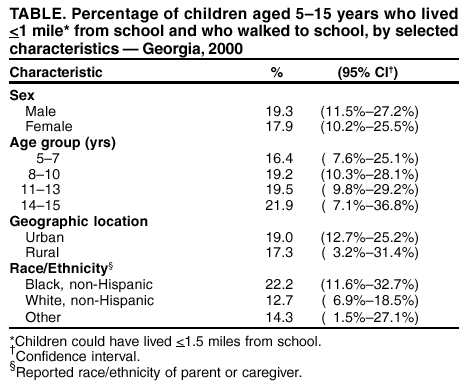

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. School Transportation Modes --- Georgia, 2000Moderate physical activity (e.g., walking or bicycling) offers substantial health benefits (1--3). Physical activity is especially important for young persons not only because of its immediate benefits but also because participation in healthy behaviors early in life might lead to healthier lifestyles in adulthood (4). Persons aged >2 years should engage in >30 minutes of moderately intense physical activity on all or most days of the week (1). However, sedentary after-school activities (e.g., watching television or using computers), decreased participation in physical education, and fewer students walking or riding their bicycles to school might contribute to the high rate of childhood obesity (5). Walking to school provides a convenient opportunity for children to be physically active. To examine modes of transportation to school for Georgia children, the Georgia Division of Public Health analyzed data from the Georgia Asthma Survey conducted during May--August 2000. This report summarizes the results of that analysis, which indicate that <19% of Georgia school-aged children who live <1 mile from school walk to school the majority of days of the week. Statewide surveillance data of school transportation modes should be collected to monitor prevalence of walking to school. Data on modes of transportation to school were collected as part of the Georgia Asthma Survey, a statewide, representative, random-digit--dialed telephone survey of Georgia households with children conducted during May--August 2000. A parent or caregiver in households with at least one child aged <18 years reported on all children residing in the home. A total of 1,503 households were sampled, representing 2,700 children. The response rate was 60%. Respondents were asked about the mode of transportation to school and the distance between home and school rounded to the nearest mile. Weighted percentages were obtained using by SAS and SUDAAN. The analysis was limited to school-aged children under the driving age, which resulted in a sample of 1,656 children aged 5--15 years who attended school. Additional analyses were performed for a subset of children (n=315) who lived <1 mile from school. Of 1,656 children aged 5--15 years included in the survey, 64 (4.2%) (95% confidence interval [CI]=2.9%--5.5%) walked to school the majority of days of the week, 775 (48.9%) (95% CI=45.7%--52.1%) rode a school bus, and 755 (43.3%) (95% CI=40.4%--46.8%) were driven to school by an adult. The remaining 62 (3.6%) (95% CI=2.5%--4.7%) were home-schooled, rode a public bus, were driven by another student, used some other mode of transportation, or used a method of transit that the caregiver either declined to identify or did not know. Of the 315 (19.0%) children who lived <1 mile from school, 56 (18.6%; 95% CI=12.8%--24.4%) walked to school the majority of days of the week, 106 (33.4%; 95% CI=26.3%--40.5%) rode a school bus, 132 (41.9%; 95% CI=34.6%--49.2%) were driven to school by an adult, and 21 (6.1%; 95% CI=2.6%--8.5%) were home-schooled, rode a public bus, were driven by another student, used some other mode of transportation, or used a method of transit that the caregiver declined to identify or did not know. Older children were more likely to walk to school than younger children, and non-Hispanic black children were more likely to walk to school than children of other racial/ethnic groups. However, these comparisons and those between sexes and between urban and rural residents were not statistically significant (Table). Reported by: SK Bricker, MPH, D Kanny, PhD, A Mellinger-Birdsong, MD, KE Powell, MD, Georgia Dept of Human Resources, Div of Public Health. JL Shisler, MPH, Div of Nutrition and Physical Activity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Editorial Note:Fewer than 19% of Georgia's school children who lived <1 mile of school walked to school the majority of days of the week. One of the national health objectives for 2010 is to increase the proportion of children's trips to school <1 mile made by walking from 31% to 50% (objective 22.14) (6). Walking has gained increased attention as an important way for persons to make physical activity a part of their daily routines. Walk-to-school programs have been developed to promote increased physical activity and safety by encouraging children to walk and bicycle to school in groups supervised by an adult and to encourage communities to develop safe routes to school. Georgia ranks 39th in level of physical inactivity among school-aged children, probably contributing to the state's relatively high level of obesity; Georgia's rate of obesity more than doubled during 1991--2000 (7). In addition, data on school transportation modes in Georgia indicate that the proportion of children walking to school on the majority of days of the week for all school trips and walking by children who live <1 mile from school are below both the Nationwide Personal Transportation Survey (NPTS) national average and the national health objective for 2010 (6,7). For children who live <1 mile from school, unsafe routes and social or cultural norms (e.g., reliance on motor-vehicle transportation) might be reasons for not walking to school. More research is needed to identify the social and environmental determinants or correlates of walking to school. The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, the distance between school and home was reported to the nearest mile, so children classified as living <1 mile from school could have lived <1.5 miles from school. Because of rounding, the average distance walked could not be calculated accurately. Second, these data cannot be compared directly with data collected from NPTS because of differences in methodology. The Georgia Asthma Survey asked for each child's mode of transportation to school on the majority of days of the week, and NPTS respondents were asked to provide information, including the purpose of the trip, distance traveled, and travel mode on all travel during a randomly selected 24-hour period. Data on the prevalence of different modes of transportation to school are typically not available at the state or local level. Such information is important for planning and evaluating programs designed to increase children's physical activity. In Georgia, two questions were added to a more extensive survey about childhood asthma. In the fall of 2002, the Georgia Asthma Survey will collect data on barriers to walking and bicycling to school in addition to modes of transportation to school. Georgia school boards are not mandated to require physical education for all students. Because children have fewer opportunities to be active physically, innovative approaches are needed to encourage children to establish active lifestyles and healthy behavior. Walking to school is an easily understood activity with historic precedent and potential benefits beyond increased physical activity, including reduced reliance on motor-vehicle transport and increased opportunities to teach children safe pedestrian skills. Walk-to-school initiatives (e.g., International Walk to School Day [8], CDC's KidsWalk-to-School program [9], and California's Safe Routes to School legislation [10]) promote educational, behavioral, policy, and environmental interventions to make walking and bicycling to school safe and convenient for children. References

Table  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 8/15/2002 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 8/15/2002

|