|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

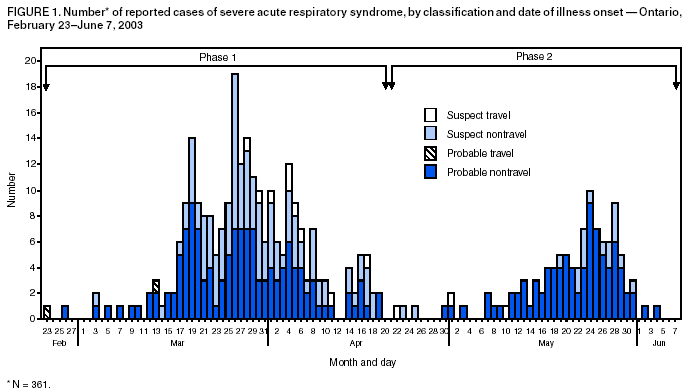

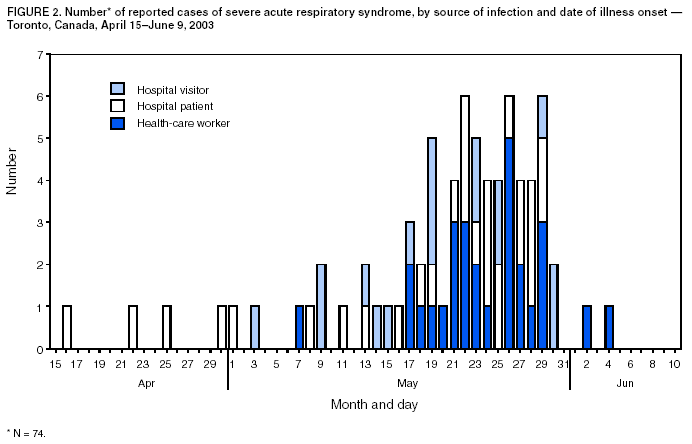

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Update: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome --- Toronto, Canada, 2003Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) was first recognized in Toronto in a woman who returned from Hong Kong on February 23, 2003 (1). Transmission to other persons resulted subsequently in an outbreak among 257 persons in several Greater Toronto Area (GTA) hospitals. After implementation of provincewide public health measures that included strict infection-control practices, the number of recognized cases of SARS declined substantially, and no cases were detected after April 20. On April 30, the World Health Organization (WHO) lifted a travel advisory issued on April 22 that had recommended limiting travel to Toronto. This report describes a second wave of SARS cases among patients, visitors, and health-care workers (HCWs) that occurred at a Toronto hospital approximately 4 weeks after SARS transmission was thought to have been interrupted. The findings indicate that exposure to hospitalized patients with unrecognized SARS after a provincewide relaxation of strict SARS control measures probably contributed to transmission among HCWs. The investigation underscores the need for monitoring fever and respiratory symptoms in hospitalized patients and visitors, particularly after a decline in the number of reported SARS cases. During February 23--June 7, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care received reports of 361 SARS cases (suspect: 136 [38%]; probable: 225 [62%]) (Figure 1); as of June 7, a total of 33 (9%) persons had died. Of 74 cases reported during April 15--June 9 to Toronto Public Health, 29 (39%) occurred among HCWs, 28 (38%) occurred as a result of exposure during hospitalization, and 17 (23%) occurred among hospital visitors (Figure 2). Of the 74 cases, 67 (90%) resulted directly from exposure in hospital A, a 350-bed GTA community hospital. The majority of cases were associated with a ward used primarily for orthopedic patients (14 rooms) and gynecology patients (seven rooms). Nursing staff members used a common nursing station, shared a washroom, and ate together in a lounge just outside the ward. SARS attack rates among nurses assigned routinely to the orthopedic and gynecology sections of the ward were approximately 40% and 25%, respectively. During early and mid-May, as recommended by provincial SARS-control directives, hospital A discontinued SARS expanded precautions (i.e., routine contact precautions with use of an N95 or equivalent respirator) for non-SARS patients without respiratory symptoms in all hospital areas other than the emergency department and the intensive care unit (ICU). In addition, staff no longer were required to wear masks or respirators routinely throughout the hospital or to maintain distance from one another while eating. Hospital A instituted changes in policy on May 8; the number of persons allowed to visit a patient during a 4-hour period remained restricted to one, but the number of patients who were allowed to have visitors was increased. On May 20, five patients in a rehabilitation hospital in Toronto were reported with febrile illness. One of these five patients was determined to have been hospitalized in the orthopedic ward of hospital A during April 22--28, and a second was found on May 22 to have SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) by nucleic acid amplification test. On investigation, a second patient was determined to have been hospitalized in the orthopedic ward of hospital A during April 22--28. After the identification of these cases, an investigation of pneumonia cases at hospital A identified eight cases of previously unrecognized SARS among patients. The first patient linked to the second phase of the Ontario outbreak was a man aged 96 years who was admitted to hospital A on March 22 with a fractured pelvis. On April 2, he was transferred to the orthopedic ward, where he had fever and an infiltrate on chest radiograph. Although he appeared initially to respond to antimicrobial therapy, on April 19, he again had respiratory symptoms, fever, and diarrhea. He had no apparent contact with a patient or an HCW with SARS, and aspiration pneumonia and Clostridium difficile--associated diarrhea appeared to be probable explanations for his symptoms. In the subsequent outbreak investigation, other patients in close proximity to this patient and several visitors and HCWs linked to these patients were determined to have SARS. At least one visitor became ill before the onset of illness of a hospitalized family member, and another visitor was determined to have SARS although his hospitalized wife did not. On May 23, hospital A was closed to all new admissions other than patients with newly identified SARS. Soon after, new provincial directives were issued, requiring an increased level of infection-control precautions in hospitals located in several GTA regions. HCWs at hospital A were placed under a 10-day work quarantine and instructed to avoid public places outside work, avoid close contact with friends and family, and to wear a mask whenever public contact was unavoidable. As of June 9, of 79 new cases of SARS that resulted from exposure at hospital A, 78 appear to have resulted from exposures that occurred before May 23. Reported by: T Wallington, MD, L Berger, MD, B Henry, MD, R Shahin, MD, B Yaffe, MD, Toronto Public Health; B Mederski, MD, G Berall, MD, North York General Hospital; M Christian, MD, A McGeer, MD, D Low, MD, Univ of Toronto; Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Toronto. T Wong, MD, T Tam, MD, M Ofner, L Hansen, D Gravel, A King, MD, Health Canada, Ottawa. SARS Investigation Team, CDC. Editorial Note:On May 14, 2003, WHO removed Toronto from the list of areas with recent local SARS transmission because 20 days (i.e., twice the maximum incubation period) had elapsed since the most recent case of locally acquired SARS was isolated or a SARS patient had died, suggesting that the chain of transmission had terminated. Before recognition of the second phase of the outbreak, the most recent case of locally acquired SARS in Toronto was reported before April 20. However, unrecognized transmission, limited initially to patient-to-patient and patient-to-visitor transmission, apparently was continuing in hospital A. After directives for increased hospitalwide infection-control precautions were lifted, an increase in the number of cases was observed, particularly among HCWs. The findings from this investigation underscore the importance of controlling health-care--associated SARS transmission and highlight the difficulty in determining when expanded precautions for SARS no longer are necessary. Investigations in Canada and other countries have identified HCWs to be at increased risk for SARS, and methods for performing surveillance among HCWs have been recommended (2). The Toronto investigation suggests that unrecognized patient-to-patient and patient-to-visitor transmission of SARS might have been occurring with no associated cases of HCW illness until after a provincewide lifting of the expanded precautions for SARS. Transient carriage of pathogens on the hands of HCWs is the most common form of transmission for several nosocomial infections, and both direct contact and droplet spread appear to be major modes for transmitting SARS-CoV (3). HCWs should be directed to use gloves appropriately (e.g., change gloves after every patient contact and avoid their use outside a patient's room) and to pay scrupulous attention to hand hygiene before putting on and after removing gloves. In addition to active and passive surveillance for fever and respiratory symptoms among HCWs, early detection of SARS cases among persons in health-care facilities in SARS-affected areas is critical, particularly in facilities that provide care to SARS patients. Identifying hospitalized patients with SARS is difficult, especially when no epidemiologic link has been recognized and the presentation of symptoms is nonspecific. Patients with SARS might develop symptoms common to hospitalized patients (e.g., fever or prodromal symptoms of headache, malaise, and myalgias), and diagnostic testing to detect cases is limited. Available nucleic acid amplification assays for SARS-CoV have reported sensitivities as low as 50% (4). Although serologic testing for SARS-CoV antibody is available, definitive interpretation of an initial negative test requires a convalescent specimen to be obtained >21 days after onset of symptoms (5). Several potential approaches for monitoring patients might improve recognition of SARS in hospitalized patients. A standardized assessment for SARS (e.g., clinical, radiographic, and laboratory criteria) might be used among all hospitalized patients with new-onset fever, especially for units or wards in which clusters of febrile patients are identified. In addition, some hospital computer information systems might allow review of administrative and physician order data to monitor selected observations that might serve as triggers for further investigation. The Toronto investigation found early transmission of SARS to both patients and visitors in hospital A. In areas affected recently by SARS, clusters of pneumonia occurring in either visitors to health-care facilities or HCWs should be evaluated fully to determine if they represent transmission of SARS. To facilitate detection and reporting, clinicians in these areas should be encouraged to obtain a history from pneumonia patients of whether they visited or worked at a health-care facility and whether family members or close contacts also are ill. Targeted surveillance for community-acquired pneumonia in areas recently affected by SARS might provide another means for early detection of these cases. The findings from the Toronto investigation indicate that continued transmission of SARS can occur among patients and visitors during a period of apparent HCW adherence to expanded infection-control precautions for SARS. Maintaining a high level of suspicion for SARS on the part of health-care providers and infection-control staff is critical, particularly after a decline in reported SARS cases. The prevention of health-care--associated SARS infections must involve HCWs, patients, visitors, and the community. References

Figure 1  Return to top. Figure 2  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 6/12/2003 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 6/12/2003

|