|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

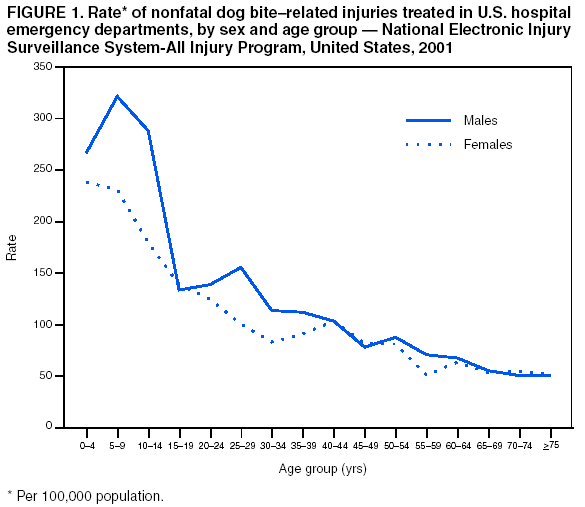

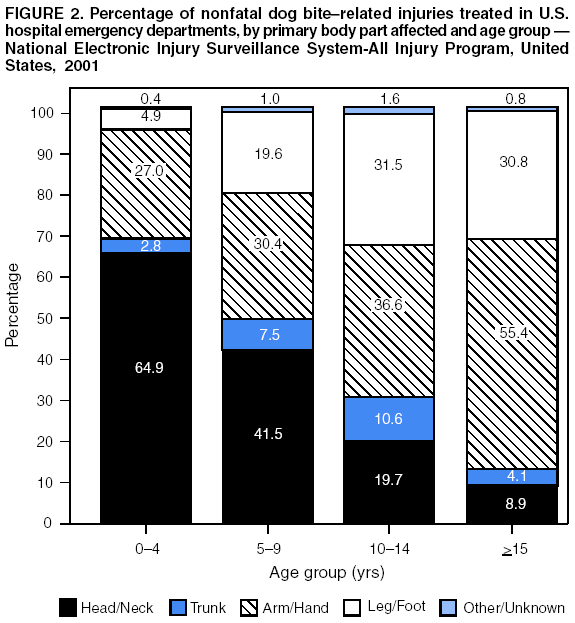

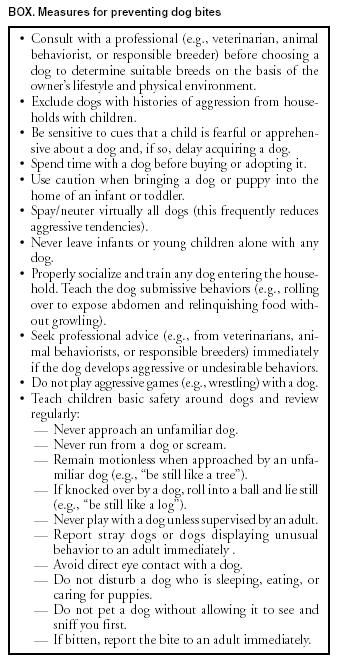

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Nonfatal Dog Bite--Related Injuries Treated in Hospital Emergency Departments --- United States, 2001In 1994, the most recent year for which published data are available, an estimated 4.7 million dog bites occurred in the United States, and approximately 799,700 persons required medical care (1). Of an estimated 333,700 patients treated for dog bites in emergency departments (EDs) in 1994 (2), approximately 6,000 (1.8%) were hospitalized (3). To estimate the number of nonfatal dog bite--related injuries treated in U.S. hospital EDs, CDC analyzed data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-All Injury Program (NEISS-AIP). This report summarizes the results of the analysis, which indicate that in 2001, an estimated 368,245 persons were treated in U.S. hospital EDs for nonfatal dog bite--related injuries. Injury rates were highest among children aged 5--9 years. To reduce the number of dog bite--related injuries, adults and children should be educated about bite prevention, and persons with canine pets should practice responsible pet ownership (Box). NEISS-AIP is operated by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission and collects data about initial visits for all types and causes of injuries treated in U.S. EDs (4). NEISS-AIP data are drawn from a nationally representative subsample of 66 out of 100 NEISS hospitals, which were selected as a stratified probability sample of hospitals with a minimum of six beds and a 24-hour ED in the United States and its territories. NEISS-AIP provides data on approximately 500,000 injury- and consumer product--related ED cases each year. The analysis included every nonfatal injury treated in a NEISS-AIP hospital ED in 2001 for which "dog bite" was listed as the external cause of injury. Because deaths are not captured completely by NEISS-AIP, patients who were dead on arrival or died in EDs were excluded. Each case was assigned a sample weight based on the inverse probability of selection; these weights were added to provide national estimates of dog bite--related injuries. Estimates were based on weighted data for 6,106 patients with dog bite--related injuries treated at NEISS-AIP hospital EDs during 2001. Confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by using a direct variance estimation procedure that accounted for the sample weights and complex sample design. Rates were calculated by using U.S. Census Bureau population estimates for 2001 (5). In 2001, an estimated 368,245 persons were treated for dog bite--related injuries (rate: 129.3 per 100,000 population) (Table). The injury rate was highest for children aged 5--9 years and decreased with increasing age. Approximately 154,625 (42.0%) dog bites occurred among children aged <14 years; the rate was significantly higher for boys (293.2 per 100,000 population) than for girls (216.7) (p = 0.037) (Figure 1). For persons aged >15 years, the difference between the rate for males (102.9) and females (88.0) was not statistically significant. The number of cases increased slightly during April--September, with a peak in July (11.1%). For injured persons of all ages, approximately 16,526 (4.5%) dog bite injuries were work-related (e.g., occurred to persons who were delivering mail, packages, or food; working at an animal clinic or shelter; or doing home repair work or installations). For persons aged >16 years, approximately 16,476 (7.9%) dog bite injuries were work-related. Injuries occurred most commonly to the arm/hand (45.3%), leg/foot (25.8%), and head/neck (22.8%). The majority (64.9%) of injuries among children aged <4 years were to the head/neck region; this percentage decreased significantly with age (p<0.01) (Figure 2). Injuries to the extremities increased with age (p<0.01) and accounted for 86.2% of injuries treated in EDs for persons aged >15 years. Injury diagnoses were described frequently as "dog bite" (26.4%); other diagnoses included puncture (40.2%), laceration (24.7%), contusion/abrasion/hematoma (6.0%), cellulitis/infection (1.5%), amputation/avulsion/crush (0.8%), and fracture/dislocation (0.4%). Overall, 98.2% of patients were treated and released from the ED. Narrative comments in the medical records note common circumstances in which children and adults incurred dog bite--related injuries. Examples among children included a girl aged 18 months who was attacked by the family dog in the backyard and sustained an open depressed skull fracture, mandible fractures, and avulsion of an ear and part of a cheek; a boy aged 4 years who was bitten on the lip by a dog that was guarding her pups; and a girl aged 3 years who was bitten on the face when trying to take food away from the family dog. Examples among adults included a man aged 34 years who sustained an avulsion laceration to his left thumb while trying to break up a fight between his dogs; a woman aged 27 years who sustained multiple puncture wounds to her forearm, thumb, and chest while trying to help her dog, which had been hit by a car; and a woman aged 75 years who was bitten while she was trying to prevent her dog from attacking an Emergency Medical Technician who was attempting to transport her from home by ambulance. Reported by: J Gilchrist, MD, Div of Unintentional Injury Prevention; K Gotsch, MPH, JL Annest, PhD, G Ryan, PhD, Office of Statistics and Programming, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC. Editorial Note:In 2001, an estimated 68 million canines were kept as pets in the United States (6). This report is the first that uses data from an ongoing surveillance system to provide national estimates of the number of dog bite--related injuries treated in EDs. In 2001, an estimated 368,245 persons were treated for dog bites in EDs; this finding is consistent with a previous estimate of 334,000 persons treated annually for dog bites in EDs during 1992--1994 (2). Of the estimated 368,245 persons treated for dog bites in EDs, an estimated 154,625 (42%) were aged <14 years. Higher rates of dog bites for children aged <14 years also are consistent with previous reports (1,7). Narrative comments from medical records describing dog bite events underscore the importance of prevention messages. Because children have higher rates of dog bites, prevention programs often are targeted to this group. Although boys aged <14 years have higher rates than girls the same age, all children need to be taught how to respond to dogs. A randomized controlled trial of a school-based intervention in Australia that taught children how to behave around and interact with dogs documented a substantial decrease in children's approach to and interaction with a strange dog (8). CDC is funding an evaluation of a similar school-based education program in Georgia aimed at increasing children's understanding of how to behave around and interact with dogs. In addition to educating children properly, prevention efforts should encourage responsible dog ownership, including training, socializing, and neutering family pets. Previous research has indicated that the majority (80%) of dog bites incurred by persons aged <18 years are inflicted by a family dog (30%) or a neighbor's dog (50%) (9). During 1997--1998, a total of 75% of fatal dog bites were inflicted on family members or guests on the family's property (10). In 2001, an estimated 16,476 (8%) dog bites to persons aged >16 years were work-related, including some that occurred while persons were visiting homes as part of their work activities. Additional strategies to encourage responsible pet ownership and reduce dog bites include regulatory measures (e.g., licensing, neutering, and registration programs and programs to control unrestrained animals) and legislation (7). "Dangerous" dog laws focus on dogs of any breed that have exhibited harmful behavior (e.g., unprovoked attacks on persons or animals) and place primary responsibility for a dog's behavior on the owner. Because a dog's tendency to bite depends on other factors in addition to genetics (e.g., medical and behavioral health, early experience, socialization and training, and victim behavior), such laws might be more effective than breed-specific legislation (7). These prevention strategies require further evaluation. The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, only nonfatal injuries treated in hospital EDs were included, and injuries treated in health-care facilities outside of an ED (e.g., a physician's office or an urgent care center) or those for which no care was received were not included. Previous estimates indicate that 17% of dog bite--related injuries are treated in medical facilities, of which 38% are seen in hospital EDs (1). Second, injury diagnoses were not specified for 26% of cases. Third, limited data are available on the circumstances of the event or the dog involved. Fourth, NEISS-AIP is designed to provide national estimates and does not provide state or local estimates. Finally, although the extent of human exposure to dogs might vary by age, sex, season, or other factors, these data are not available; as a result, the analysis did not account for exposure. Prevention programs should educate both children and adults about bite prevention and responsible pet ownership. Additional information about preventing dog bites is available at http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/duip/dogbites.htm. Acknowledgments This report is based on data contributed by T Schroeder, MS, C Downs, A McDonald, MA, and other staff of the Div of Hazard and Injury Data Systems, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. P Holmgreen, MS, Office of Statistics and Programming, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC. References

Figure 1  Return to top. Figure 2  Return to top. Table  Return to top. Box  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 7/3/2003 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 7/3/2003

|