|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

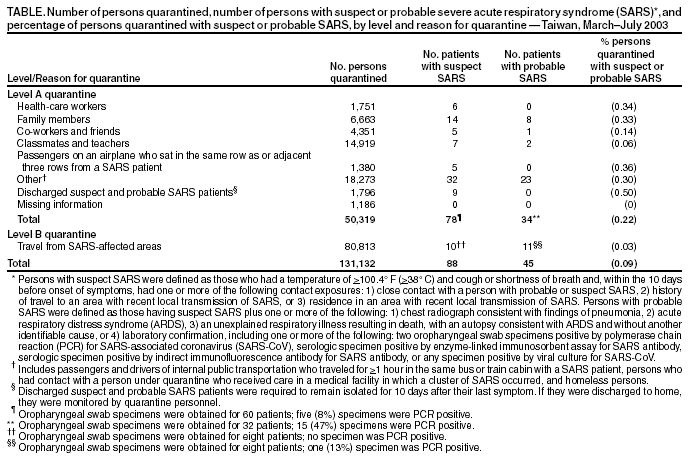

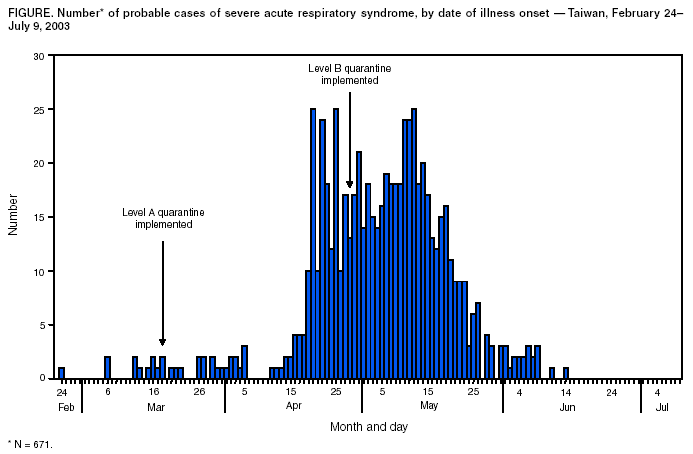

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Use of Quarantine to Prevent Transmission of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome --- Taiwan, 2003On July 5, 2003, Taiwan was removed from the World Health Organization (WHO) list of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)--affected countries. As of July 9, a total of 671 probable cases of SARS had been reported in Taiwan (Figure). On February 21, the first identified SARS patient in Taiwan returned from travel to Guangdong Province, mainland China, by way of Hong Kong. Initial efforts to control SARS appeared to be effective; these efforts included isolation of suspect and probable SARS patients, use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for health-care workers (HCWs) and visitors, and quarantine of contacts of known SARS patients (1). However, beginning in mid-April, unrecognized cases of SARS led to a large nosocomial cluster and subsequent SARS-associated coronavirus transmission to other health-care facilities and community settings (2). In response to the growing epidemic, additional measures were taken to limit nosocomial and community transmission of SARS, including more widespread use of quarantine. By the end of the epidemic, 131,132 persons had been placed in quarantine, including 50,319 close contacts of SARS patients and 80,813 travelers from WHO-designated SARS-affected areas (Table). This report describes the quarantine measures used in Taiwan and discusses the need for further evaluation of quarantine and other control measures used to prevent SARS. Beginning March 18, persons who had been in close contact with a SARS patient were quarantined for 10--14 days (Level A quarantine) (Figure); initially, quarantine was for 14 days, but after June 10, the time was changed to 10 days in accordance with the incubation period for SARS. Close contact was defined as the following eight types of exposures: 1) HCWs who were not wearing PPE when evaluating and/or treating a SARS patient; 2) family members who provided care for a SARS patient; 3) persons who worked in the same office and whose cubicles or work stations were located within 3 meters (10 feet) of a SARS patient's work area; 4) friends of a SARS patient, as deemed appropriate by local health authorities; 5) classmates or teachers of a SARS patient who attended a class for >1 hour with the patient; 6) persons who sat in the same or adjacent three rows from a SARS patient on an airplane flight; 7) passengers and drivers of public transportation who traveled for >1 hour in the same bus or train cabin with a SARS patient; and 8) persons who had contact with a person under quarantine who received care in a medical facility in which a cluster of SARS occurred. Hospital staff and patients who had contact with a SARS patient were quarantined, usually in a health-care facility. All others were quarantined at home. Homeless persons, who often use hospital toilet facilities, were asked to go voluntarily to government quarantine centers under Level A quarantine. During April 28--July 4, travelers arriving on airplane flights from WHO-designated SARS-affected areas were quarantined for 10 days (Level B quarantine). Arriving passengers could choose quarantine in an airport transit hotel, at home, or at a quarantine site designated and paid for by their employer. If these options were not available, the traveler was quarantined at a government quarantine center located at military bases. On June 9, quarantine regulations were eased for staff of Taiwanese companies based in mainland China who were returning to Taiwan for business. Travelers in this category were allowed to conduct business if they wore surgical masks. When not conducting business, they were to follow the rules of quarantine. Persons under quarantine were required to stay where they were quarantined; take their temperature two to three times a day; seek medical attention promptly if they had fever (>100.4º F [>38º C]), cough, shortness of breath, or other respiratory symptoms; cover their nose and mouth with tissue paper when coughing or sneezing; and wear surgical masks when around other persons and outside the quarantine site. They were not allowed to use public transportation, visit hospitalized patients, or visit crowded public places. Persons under Level A quarantine could leave the quarantine site only for activities deemed necessary by local health authorities; meals were delivered. Persons under Level B quarantine were allowed to leave the quarantine site to seek medical attention, exercise in an open area, purchase meals, dispose of garbage, and perform other activities deemed necessary by local health authorities. All outdoor trips were recorded to facilitate possible future investigations. Failure to comply with quarantine regulations, submitting incomplete SARS survey forms, or providing inaccurate contact information was punishable by fines of U.S. $1,765--$8,824 and incarceration of <2 years. The direct management and supervision of persons under quarantine was conducted by local HCWs or civil servants. This activity included ensuring the initial registration of all persons requiring quarantine; recording each person's whereabouts, with information obtained either by daily visits or telephone calls; overseeing the person's daily temperature recordings; evaluating patients who reported a fever; and directing persons with possible SARS to appropriate medical attention. Local health officials reported daily on the status of quarantined persons to the Taiwan Department of Health through a web-based database. In addition to these measures, video monitoring was conducted for some persons who were contacts of a SARS patient and quarantined at home. Although the intervention was conceived initially for quarantine violators who were residents of the high-population density areas of Taipei and Kaohsiung, the low number of quarantine violators allowed broader use of this intervention. By mid-May, video monitoring was used for almost all persons living in these cities and under quarantine at home. At government quarantine facilities, persons were placed in individual rooms (not negative-pressure); meals were delivered. Police guarded the rooms to ensure compliance with quarantine. Several social supports were developed to ease the burden of quarantine on persons and their families. Service providers telephoned quarantined persons to provide psychologic support. Care was provided for the family members of quarantined persons, including day care and care for ill persons. Persons who completed quarantine received the equivalent of U.S. $147. Quarantined persons could request other social services from local health or civil affairs departments. Of the 131,132 persons who were quarantined during the SARS epidemic in Taiwan, 286 (0.2%) were fined for violation of quarantine. Of the 50,319 persons placed under Level A quarantine, 4,063 (8.0%) were placed on video monitoring at home. A total of 112 (0.22%) persons had suspect or probable SARS diagnosed while under Level A quarantine. Of the 80,813 persons placed under Level B quarantine, 21 (0.03%) had suspect or probable SARS diagnosed. The highest percentage of persons who had suspect or probable SARS diagnosed subsequently were among HCWs exposed to a SARS patient (0.34%), family members of a SARS patient (0.33%), and persons on the same airplane flight who sat within three rows of a SARS patient (0.36%). Travelers arriving from SARS-affected areas had the lowest percentage for subsequent SARS diagnosis (0.03%). Oropharyngeal swab specimens were obtained from 68 (77.0%) of 88 patients with suspect SARS (Table); five (7.0%) specimens tested positive by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Oropharyngeal swab specimens were obtained from 40 (88.0%) of 45 patients with probable SARS; 16 (40.0%) specimens were PCR positive. Reported by: ML Lee, MD, CJ Chen, ScD, IJ Su, MD, KT Chen, MD, CC Yeh, MD, CC King, PhD, HL Chang, MPH, YC Wu, MD, MS Ho, MD, DD Jiang, PhD, WF Lin, MPH, HC Lang, PhD, T Lin, MPH, MH Lai, MPH, JT Wang, CH Chen, MD, SARS Prevention Task Force, Executive Yuan, Taiwan, Republic of China. World Health Organization, Dept of Communicable Disease Surveillance and Response, Geneva, Switzerland. Taiwan SARS Investigative Team, CDC. Editorial Note:Quarantine, the separation and/or restriction of movement of persons who are not ill but are believed to have been exposed to infection to prevent transmission of diseases, was developed in the 14th century but has been implemented rarely on a large scale during the past century (3,4). The SARS pandemic has demonstrated that governments and public health officials might use quarantine as a public health tool to prevent infectious diseases, particularly when other preventive interventions (e.g., vaccines and antibiotics) are unavailable. In Taiwan, only a small percentage of persons quarantined had suspect or probable SARS diagnosed subsequently, and an even smaller percentage of persons quarantined had a laboratory-confirmed case of SARS. However, because one infected person could expose others and generate successive waves of infection, the use of quarantine might have prevented additional cases. This possibility should be examined through future mathematical modeling studies. Taiwan was one of several countries that implemented quarantine measures during the global SARS outbreak, and more study is needed to determine whether the logistics and costs of quarantine warrant its use. Such studies should examine both the direct (e.g., stipends, resources, personnel time, and lost work days) and indirect (e.g., social stigma, curtailment of civil liberties [e.g., restrictions on freedom of movement], declining personal and community mental health, and delay in reporting symptoms) costs of quarantine. Numerous SARS control measures were undertaken simultaneously, making it difficult to determine the independent contribution of any one measure. These other control measures included designating dedicated SARS hospitals throughout the island; constructing additional negative-pressure rooms; instituting fever-screening clinics for all health-care facilities; performing fever screening on all persons entering public buildings and restaurants; and requiring masks for all persons working in restaurants, entering hospitals, and using public transportation systems. Evaluation of the contribution of all control measures, including quarantine, should be performed to determine the appropriate role of each intervention in response to future outbreaks. References

Table  Return to top. Figure  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 7/24/2003 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 7/24/2003

|