|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

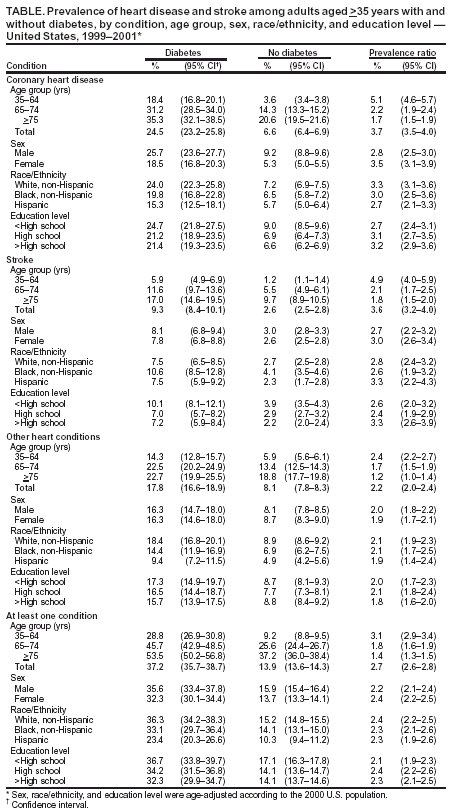

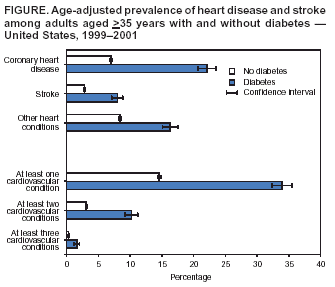

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Self-Reported Heart Disease and Stroke Among Adults With and Without Diabetes --- United States, 1999--2001Heart disease and stroke are the first and third leading causes of death among U.S. adults (1). Adults with diabetes have a twofold to fourfold greater risk for dying from cardiovascular diseases than adults without diabetes (1). In addition, although the annual incidence of deaths attributed to cardiovascular diseases declined substantially among U.S. adults during 1970--1994, it decreased less among those with diabetes (2). To compare the prevalence of heart disease and stroke among adults with and without diabetes, CDC analyzed data from the 1999--2001 National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS). This report summarizes the results of that analysis, which indicate that the age-adjusted prevalence of heart disease and stroke is approximately two to three times greater among adults with diabetes than among adults without diabetes. Increased efforts are needed to prevent diabetes and reduce the prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors (e.g., hypertension and high cholesterol) in the United States, particularly among adults with diabetes. NHIS is a stratified, multistage probability sample survey representing the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population. In this analysis, only data for respondents aged >35 years were analyzed because of the low prevalence of cardiovascular disease among young adults and children. For 1999, 2000, and 2001, response rates were 69.6%, 72.1%, and 73.8%, respectively. Respondents were classified as having diabetes if they answered "yes" to the question, "Have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?" Women who had diabetes only during pregnancy were classified as not having diabetes. Respondents were classified as having a cardiovascular condition if they reported having a medical history of at least one of the following: coronary heart disease (CHD) including angina pectoris and myocardial infarction; stroke; or another type of heart condition (other than CHD, angina pectoris, and myocardial infarction). The prevalence of each condition was determined for the overall U.S. population with and without diabetes and for specific demographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education level). Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the demographically adjusted probability of having heart disease or stroke diagnosed. Because no substantial difference was observed between the age-adjusted and adjusted prevalences for all demographic characteristics, only the age-adjusted prevalences of heart disease and stroke are presented for each population. Prevalence ratios were calculated by dividing the prevalence of heart disease or stroke among adults with diabetes by the prevalence among adults without diabetes. Chi square analysis was used to test for statistical significance, and SUDAAN was used to calculate confidence intervals (CIs). Data were weighted to reflect the age, sex, and racial/ethnic distribution of the adult U.S. population. During 1999--2001, adults with diabetes were significantly more likely than adults without diabetes to report a history of CHD (24.5% versus 6.6%), stroke (9.3% versus 2.6%), other heart condition (17.8% versus 8.1%), and at least one of these conditions (37.2% versus 13.9) (Table). After data were adjusted for age, adults with diabetes were 3.2 (95% CI = 2.9--3.4) times more likely than those without diabetes to report a history of CHD, 2.9 (95% CI = 2.5--3.2) times more likely to report a history of stroke, and 1.9 (95% CI = 1.8--2.1) times more likely to report another heart condition (Figure). These differences were greatest among adults aged 35--64 years with diabetes, who were 5.1 times more likely to report a history of CHD, 4.9 times more likely to report a history of stroke, 2.4 times more likely to report another heart condition, and 3.1 times more likely to report at least one of these conditions than adults of similar age without diabetes (Table). Overall, adults aged >35 years with diabetes were 2.3 (95% CI = 2.2--2.4) times more likely to report having at least one condition, 3.3 (95% CI = 2.9--3.7) times more to report at least two conditions, and 5.3 (95% CI = 3.6--7.1) times more likely to report at least three conditions (Figure). Among adults with and without diabetes, the prevalence of any cardiovascular condition increased with age (p<0.05), the prevalence of CHD was higher among men than women (p<0.05), non-Hispanic whites had the highest prevalence of CHD and other heart conditions, and non-Hispanic blacks had the highest prevalence of stroke (Table). Among those with diabetes, no significant correlation was observed between education level and prevalence of heart disease or stroke. However, among those without diabetes, the prevalence of CHD and stroke was associated inversely with education level (p<0.05). Reported by: SM Benjamin, PhD, LS Geiss, MA, L Pan, MPH, MM Engelgau, MD, Div of Diabetes Translation; KJ Greenlund, PhD, Div of Adult and Community Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Editorial Note:The findings in this report indicate that the age-adjusted prevalence of reported heart disease and stroke is approximately two to three times greater among persons with diabetes than among persons without diabetes. These results are consistent with mortality data, which indicate that cardiovascular disease death rates are two to four times higher for adults with diabetes than for adults without diabetes. Antihypertensive treatment, aspirin use, lipid-lowering medication, and promotion of healthy lifestyles reduce the risk for heart disease and stroke in persons with and without diabetes (3,4). However, a substantial proportion of persons with diabetes have uncontrolled blood pressure and dyslipidemia and do not take aspirin (5). Persons with diabetes and those with heart disease also are both more likely than those without diabetes to have other risk factors associated with ill health (e.g., overweight/obesity, physical inactivity, and poor diet). In 2001, the National Diabetes Education Program (NDEP), cosponsored by CDC and the National Institutes of Health, started the "Be Smart About Your Heart: Control the ABCs of Diabetes" campaign to educate persons with diabetes about their high risk for heart disease and stroke and what they can do to lower that risk. Information about the campaign is available from NDEP at http://ndep.nih.gov/campaigns/BeSmart/BeSmart_index.htm. In addition, CDC and the Health Resources and Service Administration established the National Diabetes Collaborative, a partnership of public and private agencies, to increase access to and improve the quality of diabetes care in approximately 395 health centers. The findings of this survey identified various demographic characteristics associated with an increased prevalence of heart disease and stroke among adults with and without diabetes. For both populations, prevalences were higher among men than among women. Non-Hispanic blacks were more likely than non-Hispanic whites or Hispanics to report having had a stroke, probably because of the high prevalence of hypertension among blacks (6). Prevention of diabetes can decrease the prevalence of heart disease and stroke. Improved diet, weight loss, and increased physical activity can prevent or delay the onset of diabetes among adults with impaired glucose tolerance (7). In 2003, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services initiated the "Steps to a HealthierUS" program to reduce the prevalence of diabetes, overweight, obesity, and asthma and address physical inactivity, poor nutrition, and tobacco use. The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, NHIS data on history of diabetes, heart disease, and stroke are based on self-reports. However, rates of these conditions based on self-reports have been shown to be highly accurate and only slightly higher than those based on physician reports (8); such rates have a high validity among adults with diagnosed diabetes (9). Second, because approximately one third of U.S. adults have undiagnosed diabetes (10), the results might underestimate the difference in heart disease or stroke prevalence between adults with and without diabetes. Third, because NHIS excludes institutionalized persons, a population at high risk for illness, the results might underestimate the prevalence of heart disease and stroke. Fourth, differences in prevalence of heart disease and stroke between persons with and without diabetes in part might be due to differences in how the groups were screened for those conditions. Finally, because only survivors of heart disease and stroke were studied, the prevalence estimates might not reflect the true burden of disease in the U.S. population or in any of the demographic groups studied. Heart diseases and stroke impose a substantially greater burden on persons with diabetes than on persons without diabetes. To reduce the incidence of heart disease and stroke, a concerted effort is needed among health-care providers, public health officials, members of community-based organizations, patients, and their families. References

Table  Return to top. Figure  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 11/6/2003 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 11/6/2003

|