|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

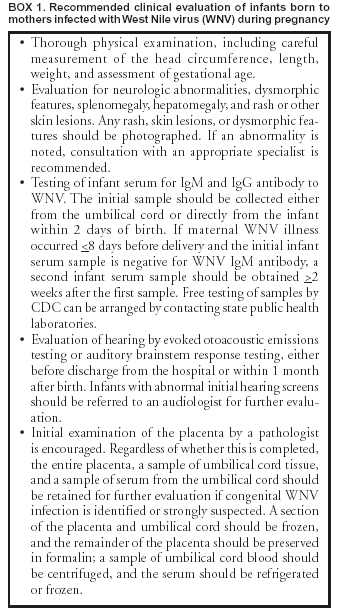

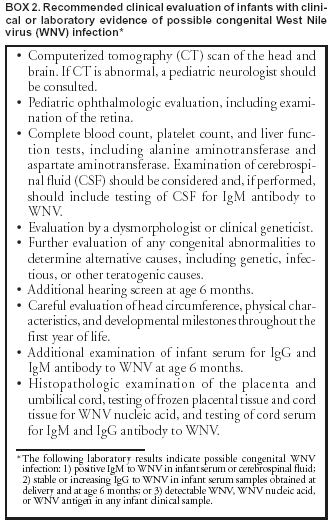

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Interim Guidelines for the Evaluation of Infants Born to Mothers Infected with West Nile Virus During PregnancyWest Nile virus (WNV) is a single-stranded RNA flavivirus with antigenic similarities to Japanese encephalitis and St. Louis encephalitis viruses. It is transmitted to humans primarily through the bites of infected mosquitoes. Flavivirus infection during pregnancy has been associated rarely with both spontaneous abortion and neonatal illness but has not been known to cause birth defects in humans (1--4). During 2002, a total of 4,156 cases of WNV illness in humans, including 2,946 cases of neuroinvasive disease, were reported to CDC by state health departments. In 2002, a woman who had WNV encephalitis during the 27th week of her pregnancy delivered a full-term infant with chorioretinitis, cystic destruction of cerebral tissue, and laboratory evidence of congenitally acquired WNV infection (5,6). Although this case demonstrated intrauterine WNV infection in an infant with congenital abnormalities, it did not prove a causal relation between WNV infection and these abnormalities. During 2002, CDC investigated three other instances of maternal WNV infection. In all three cases, the infants were born at full term with normal appearance and negative laboratory tests for WNV infection; cranial imaging studies and ophthalmologic examinations were not performed. During 2003, CDC received reports of approximately 9,100 cases of WNV illness, including approximately 2,600 cases of neuroinvasive disease*. CDC is gathering data on pregnancy outcomes for approximately 70 women with WNV illness during pregnancy (CDC, unpublished data, 2003). To develop guidelines for evaluating infants born to mothers who acquire WNV infection during pregnancy, on December 2, 2003, CDC convened a meeting of specialists in the evaluation of congenital infections. This report summarizes the interim guidelines established during that meeting. Screening for WNV During PregnancyNo specific treatment for WNV infection exists, and the consequences of WNV infection during pregnancy have not been well defined. For these reasons, screening of asymptomatic pregnant women for WNV infection is not recommended. Diagnosis of WNV Infection During PregnancyPregnant women who have meningitis, encephalitis, acute flaccid paralysis, or unexplained fever in an area of ongoing WNV transmission should have serum (and cerebrospinal fluid [CSF], if clinically indicated) tested for antibody to WNV. If serologic or other laboratory tests indicate recent infection with WNV, these infections should be reported to the local or state health department, and the women should be followed to determine the outcomes of their pregnancies. Evaluation of the Fetus in Pregnant Women with WNV InfectionIf WNV illness is diagnosed during pregnancy, a detailed ultrasound examination of the fetus to evaluate for structural abnormalities should be considered no sooner than 2--4 weeks after onset of WNV illness in the mother, unless earlier examination is otherwise indicated. Amniotic fluid, chorionic villi, or fetal serum can be tested for evidence of WNV infection. However, the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value of tests that might be used to evaluate fetal WNV infection are not known, and the clinical consequences of fetal infection have not been determined. In case of miscarriage or induced abortion, testing of all products of conception (e.g., the placenta and umbilical cord) for evidence of WNV infection is advised to document the effects of WNV infection on pregnancy outcome. Evaluation of Infants Born to Mothers Infected with WNV During PregnancyWhen an infant is born to a mother who was known or suspected to have WNV infection during pregnancy, clinical evaluation is recommended (Box 1). Further evaluation should be considered if any clinical abnormality is identified or if laboratory testing indicates that an infant might have congenital WNV infection (Box 2). Prevention of WNV Infection During PregnancyPregnant women who live in areas with WNV-infected mosquitoes should apply insect repellent to skin and clothes when exposed to mosquitoes and wear clothing that will help protect against mosquito bites. In addition, whenever possible, pregnant women should avoid being outdoors during peak mosquito-feeding times (i.e., usually dawn and dusk). Reported by: E Hayes, MD, D O'Leary, DVM, Div of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases; SA Rasmussen, MD, Div of Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC. Editorial Note:Neither the proportion of WNV infections during pregnancy that result in congenital infection nor the spectrum of clinical abnormalities associated with congenital WNV infection is known. However, one case reported in 2002 suggests that intrauterine transmission of WNV in certain instances might affect the newborn adversely. To evaluate the possible effects of WNV infection during pregnancy, CDC is gathering clinical and laboratory data on outcomes of pregnancies of women who were known or suspected to be infected with WNV during pregnancy. Guidance on diagnosis of WNV can be obtained from local or state health departments and from CDC, telephone 970-221-6400. Guidance also is available at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/westnile/resources/fact_sheet_clinician.htm. Clinicians are encouraged to report cases of WNV infections in pregnant women to their state or local health departments or CDC. Acknowledgments This report is based on contributions by JM Friedman, PhD, Univ of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. K Jones, MD, Univ of California, San Diego. M Abzug, MD, The Children's Hospital and Univ of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver; J Paisley, MD, Poudre Valley Hospital, Fort Collins; W Tyson, MD, Presbyterian/St. Luke's Hospital, Denver; M Wheeler, MD, Univ of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver; J Pape, Colorado Dept of Public Health and Environment. M Mets, MD, Children's Memorial Hospital, Chicago, Illinois. W Allan, MD, Foundation for Blood Research, Scarborough, Maine. C Meissner, MD, Tufts New England Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts. J Bale, MD, Univ of Utah and Primary Children's Medical Center, Salt Lake City, Utah. J Rutledge, MD, Children's Hospital and Regional Medical Center, Seattle, Washington. J Brown, DVM, G Campbell, MD, S Kuhn, R Lanciotti, PhD, A Marfin, MD, S Montgomery, DVM, L Petersen, MD, Div of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases; J Cordero, MD, J Mulinare, MD, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC. References

* Data as of February 18, 2004. Box 1  Return to top. Box 2  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 2/26/2004 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 2/26/2004

|