|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

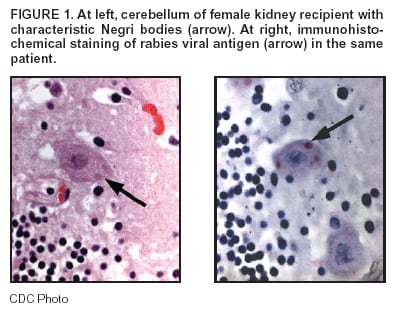

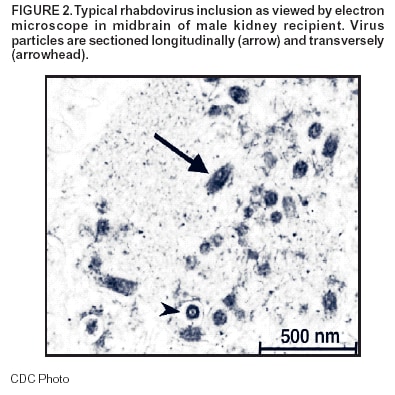

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Investigation of Rabies Infections in Organ Donor and Transplant Recipients --- Alabama, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, 2004On July 1, this report was posted as an MMWR Dispatch on the MMWR website (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr). On June 30, 2004, CDC confirmed diagnoses of rabies in three recipients of transplanted organs and in their common donor, who was found subsequently to have serologic evidence of rabies infection. The transplant recipients had encephalitis of unknown etiology after transplantation and subsequently died. Specimens were sent to CDC for diagnostic evaluation. This report provides a brief summary of the ongoing investigation and information on exposure risks and postexposure measures. Organ DonorThe organ donor was an Arkansas man who visited two hospitals in Texas with severe mental status changes and a low-grade fever. Neurologic imaging indicated findings consistent with a subarachnoid hemorrhage, which expanded rapidly in the 48 hours after admission, leading to cerebral herniation and death. Donor eligibility screening and testing did not reveal any contraindications to transplantation, and the patient's family agreed to organ donation. Lungs, kidneys, and liver were recovered. No other organs or tissues were recovered from the donor, and the donor did not receive any blood products before death. The liver and kidneys were transplanted into three recipients on May 4 at a transplant center in Texas. The lungs were transplanted in an Alabama hospital into a patient who died of intraoperative complications. Liver RecipientThe liver recipient was a man with end-stage liver disease. The patient did well immediately after transplantation and was discharged home on postoperative day 5. Twenty-one days after transplant, the patient was readmitted with tremors, lethargy, and anorexia; he was afebrile. The patient's neurologic status deteriorated rapidly during the next 24 hours; he required intubation and critical care support. A lumbar puncture indicated a mild lymphocytic pleocytosis (25 white blood cells/mm3) and a mildly elevated protein. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain indicated increased signal in the cerebrospinal fluid. His neurologic status continued to deteriorate. Six days after admission, a repeat MRI indicated diffuse encephalitis. The patient subsequently died. Female Kidney RecipientThe first kidney recipient was a woman with end-stage renal disease caused by hypertension and diabetes. She had no postoperative complications and was discharged home on postoperative day 7. Twenty-five days after transplant, she was readmitted with right-side flank pain and underwent an appendectomy. Two days after this procedure, she had diffuse twitching and was noted to be increasingly lethargic. Neurologic imaging with computed tomography and MRI indicated no abnormality. During the next 24--48 hours, the patient had worsening mental status, seizures, hypotension, and respiratory failure requiring intubation. Her mental status continued to deteriorate, and cerebral imaging 2 weeks after admission indicated severe cerebral edema. The patient subsequently died. Male Kidney RecipientThe second renal recipient was a man with end-stage renal disease caused by focal, segmental glomerulosclerosis. His posttransplant course was complicated briefly by occlusions of an arterial graft leading to infarction of the lower pole of the transplanted kidney. The patient was discharged home 12 days after transplantation. Twenty-seven days after transplantation, he visited a hospital emergency department and was then transferred to the transplant center with myoclonic jerks and altered mental status; he was afebrile. An MRI of the brain performed on admission revealed no abnormalities. His mental status deteriorated rapidly during the next 24 hours. A lumbar puncture revealed mild lymphocytic pleocytosis (16 white blood cells/mm3) and a mildly elevated protein. His mental status continued to deteriorate, leading to respiratory failure requiring intubation. A repeat MRI performed 10 days after admission indicated diffuse edema. The patient subsequently died. Laboratory InvestigationIn all three patients, histopathologic examination of central nervous system (CNS) tissues at CDC revealed an encephalitis with viral inclusions suggestive of Negri bodies; the diagnosis of rabies in all three recipients was confirmed by immunohistochemical testing and by the detection of rabies virus antigen in fixed brain tissue by direct fluorescent antibody tests (Figure 1). Electron microscopy of CNS tissue of one of the renal transplant recipients also identified characteristic rhabdovirus inclusions and viral particles (Figure 2). Suckling mice inoculated intracranially and intraperitoneally with brain tissue from one kidney recipient died 7--9 days after injection. Thin-section electron microscopy of CNS tissue of the mice had visible rhabdovirus particles, and immunohistochemical testing detected rabies viral antigens. Antigenic typing performed upon brain tissue from one recipient was compatible with a rabies virus variant associated with bats. Rabies virus antibodies were demonstrated in blood from two of the three recipients and the donor. Detecting rabies antibodies in the donor suggests that he was the likely source of rabies transmission to the organ recipients. Testing of additional donor specimens is ongoing. Reported by: Univ of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital; Jefferson County Health Dept, Birmingham; Alabama Dept of Public Health. Arkansas State Dept of Health. Oklahoma State Dept of Health. Regional and local health depts; Texas Dept of Health. Div of Healthcare Quality Promotion; Div of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC. Editorial Note:Rabies is an acute fatal encephalitis caused by neurotropic viruses in the genus Lyssavirus, family Rhabdoviridae (1). The majority of rabies cases are caused by bites by rabid mammals (1,2). Nonbite exposures, including scratches, contamination of an open wound, or direct mucous membrane contact with infectious material (e.g., saliva or neuronal tissue from rabid animals), rarely cause rabies. After an incubation period of several weeks to months, the virus passes via the peripheral nervous system and replicates in the central nervous system. Rabies virus can then be disseminated to salivary glands and other organs via neural innervation (3). Rabies can be prevented by administration of rabies postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) (4), which is highly effective in preventing rabies when administered before onset of clinical signs. Although transmission of rabies has occurred previously among eight recipients of transplanted corneas in five countries (4), this report describes the first documented cases of rabies virus transmission among solid organ transplant recipients. Infection with rabies virus likely occurred via neuronal tissue contained in the transplanted organs, as rabies virus is not spread hematologically. In collaboration with CDC, state and local health departments in Alabama, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas have initiated investigations to identify a potential source of exposure for the donor and to identify contacts of patients among health-care providers or domestic contacts who might need rabies PEP. The risk for health-care--associated transmission of rabies is extremely low; transmission of rabies virus from infected patients to health-care providers has not been documented (5). The use of Standard Precautions (6) for contact with blood and body fluids (e.g., gloves, gown, mask, goggles, or face shield as indicated for the type of patient contact) prevents exposure to the rabies virus. No laboratory-confirmed cases of human-to-human transmission of rabies among household contacts have been reported (4). No cases of rabies have been reported in association with transmission by fomites or environmental surfaces. Routes of possible exposure include percutaneous and mucocutaneous entry of the rabies virus through a wound, nonintact skin, or mucous membrane contact. Intact skin contact with infectious materials is not considered an exposure to the rabies virus. Persons with exposure as defined above to saliva, nerve tissue, or cerebral spinal fluid from any of the four infected patients should receive rabies PEP. Types of exposures in domestic settings for which administration of PEP would be appropriate include bites, sexual activity, exchanging kisses on the mouth or other direct mucous membrane contact with saliva, and sharing eating or drinking utensils or cigarettes. In health-care settings, additional opportunities that can lead to contamination of mucous membranes or nonintact skin with oral secretions include procedures such as intubation or suctioning of respiratory secretions or injuries with sharp instruments (e.g., needlesticks or scalpel cuts). Percutaneous injuries (e.g., needlesticks) are considered exposures because of potential contact with nervous tissue. Contact with patient fluids (e.g., blood, urine, or feces) does not pose a risk for rabies exposure (4). All potential organ donors in the United States are screened and tested to identify if the donor might present an infectious risk. Organ procurement organizations are responsible for evaluating organ donor suitability, consistent with minimum procurement standards (7). Donor eligibility is determined through a series of questions posed to family and contacts, physical examination, and blood testing for evidence of organ dysfunction and selected bloodborne viral pathogens and syphilis. Laboratory testing for rabies is not performed. In the case reported here, the donor's death was attributed to noninfectious causes. The role of organ donor deferral is to optimize successful transplantation in the recipient, including minimizing risk of infectious disease transmission to the lowest level reasonably achievable without unduly decreasing the availability of this life-saving resource. The benefits from transplanted organs outweigh the risk for transmission of infectious diseases from screened donors. CDC is working with federal and organ procurement agencies to review donor screening practices. Additional information about rabies and its prevention is available from CDC, telephone 404-639-1050, or at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/rabies. Additional information about organ transplantation is available at http://www.optn.org/about/donation . References

Figure 1  Return to top. Figure 2  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 7/7/2004 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 7/7/2004

|