|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

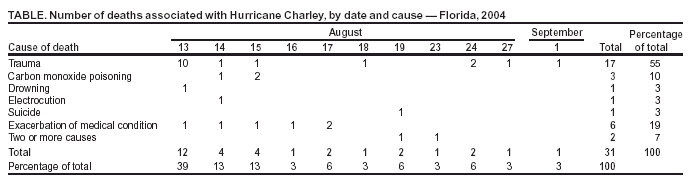

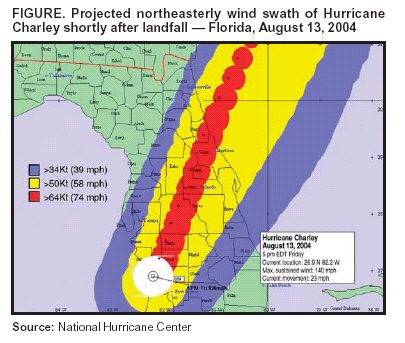

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Preliminary Medical Examiner Reports of Mortality Associated with Hurricane Charley --- Florida, 2004On August 13, 2004, at approximately 3:45 p.m. EDT, Hurricane Charley made landfall at Cayo Costa, a Gulf of Mexico barrier island west of Cape Coral, Florida, as a Category 4 storm, with sustained winds estimated at 145 mph (1). Charley was the strongest hurricane to make landfall in the United States since Hurricane Andrew in August 1992 (2). Charley created a 7-foot storm surge in Fort Myers, then traversed the state in 9 hours, continuing in a northeast direction across eight counties (Figure). This report presents preliminary data from Florida medical examiners (MEs), which indicated that 31 deaths were associated with Hurricane Charley. Deaths might be reduced through coordinated hurricane planning, focused evacuations, and advance communication to the public regarding the environmental hazards after a natural disaster. Under Florida law, all deaths related to hurricanes are reportable to MEs. A directly related death was defined as death caused by the environmental force of the hurricane. An indirectly related death was a death occurring under circumstances caused by the hurricane. Natural causes of death were considered storm related if physical stress during or after the storm resulted in exacerbation of preexisting medical conditions and death. As of September 1, a total of 31 deaths had been reported; 12 (39%) occurred on the first day of the storm, and eight (26%) additional deaths occurred during the next 2 days (Table). Decedents ranged in age from 6 to 87 years (mean: 54 years; median: 56 years); 24 (77%) were male. Of the 31 deaths, 24 (77%) were classified as unintentional injury, six (19%) were attributable to natural causes, and one death was a suicide. Of the 24 unintentional deaths, 17 (71%) were trauma related, three were caused by carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning, and one each were caused by electrocution and drowning; two deaths involved at least two factors in combination (i.e., trauma and electrocution or CO poisoning and burn). Of the 18 deaths related to trauma and drowning, 11 (62%) occurred on the day the storm made landfall. Of those 11 deaths, nine were directly related to the storm, and two were indirectly related (i.e., an automobile crash in which a traffic light was out and a fall by an evacuee in a hotel room). Four trauma deaths resulted from motor-vehicle crashes, four from falls, three from implosion of a shelter (i.e., mobile home or shed), two from falling trees, two from flying debris, one from an uncertain cause, and one from a crush injury. Of the six deaths related to natural causes, four resulted from exacerbation of cardiac conditions and two from exacerbation of preexisting pulmonary conditions. Two persons lost power during the storm and did not have access to their needed oxygen. One man likely had a heart attack during cleanup. Three men died of heart failure, one during the storm and two in the days after the storm. Of these three deaths, two were associated with exposure to extreme heat. The suicide death involved a man who became despondent after losing his home and possessions to Hurricane Charley; his death resulted from a witnessed self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. Reported by: KT Jones, Office of Vital Statistics, Jacksonville; M Grigg, Office of Planning, Evaluation & Data Analysis; LK Crockett, MD, Div of Disease Control; L Conti, DVM, Div of Environmental Health; C Blackmore, DVM, Bur of Community Environmental Health; D Ward, A Rowan, DrPH, R Sanderson, MPH, M Laidler, MPH, J Hamilton, MPH, Bur of Epidemiology, Florida Dept of Health. J Schulte, DO, Epidemiology Program Office; D Batts-Osborne, MD, National Center for Environmental Health; D Chertow, MD, EIS Officer, CDC. Editorial Note:Preliminary findings from examining the 31 deaths associated with Hurricane Charley in Florida revealed that hurricane wind effects rather than flooding or rain led to the majority of deaths. The majority of fatalities involved blunt trauma caused by injuries from falling trees, flying debris, and destroyed physical structures. Similar to Hurricane Andrew, which devastated sections of Florida in 1992, only one death was caused by drowning (2). The mortality and morbidity associated with hurricanes can vary according to particular characteristics of a storm. Strong winds instead of a huge storm surge with subsequent flooding occurred with Hurricane Charley. Advance hurricane warnings, practiced disaster plans, and coordinated evacuation procedures are crucial to limiting the adverse effects of severe weather-related events. Although forecasting systems have improved, the predicted storm paths might still change with short notice. Surrounding counties outside of the predicted path should be prepared to coordinate evacuation of residents, especially of vulnerable populations such as older adults, in a timely manner. Regional planning should include instruction on the importance of evacuation, especially of less stable structures such as mobile homes and tool sheds. In addition, the risk of operating a motor vehicle during and immediately after a hurricane should be emphasized. The findings in this report are subject to at least one limitation. A standardized, universally accepted definition of hurricane-related death does not exist, so characterization of mortality caused by natural disasters such as hurricanes often is based on ME classification. In this case, deaths were classified as unintentional injury, intentional (e.g., suicide), or natural. Local disaster plans and public health messages that address populations with special needs (e.g., older adults) should be strengthened. In this case, approximately 42% (13 of 31) of the decedents were persons aged >60 years. Older adults are more likely to have preexisting medical conditions (e.g., cardiac and respiratory problems) and are more likely to require medical supplies or equipment that depend on electricity to operate. All of the natural causes of death could be attributed to exacerbation of chronic medical conditions or to the lack of electricity, leading to extreme heat exposure or interruption of supplemental oxygen supply. The Florida Department of Health, with assistance from CDC, also conducted rapid assessments of needs of the older adult population in affected counties (3). CO poisoning from improperly located generators, electrical injuries from downed power lines, and injuries incurred during cleanup activities can occur in the aftermath of disasters. Crisis intervention for persons who experience loss of family, friends, neighbors, pets, and property is critical. Public health messages should emphasize safety precautions and should be delivered in advance of the storm, before vital services and lines of communication are interrupted. References

Table  Return to top. Figure  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 9/16/2004 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 9/16/2004

|