|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

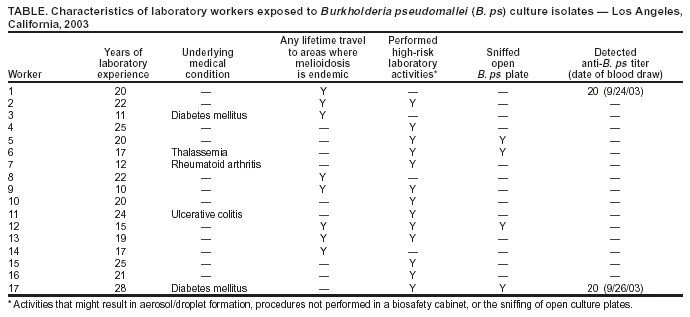

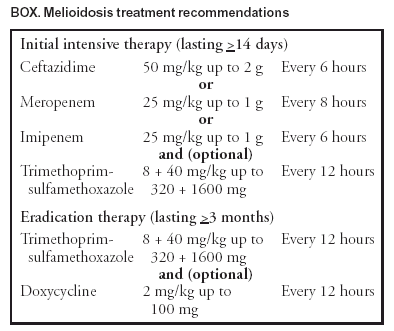

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Laboratory Exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei --- Los Angeles, California, 2003On July 26, 2003, the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services (LACDHS) received a report that a local clinical laboratory had isolated from specimens Burkholderia pseudomallei, a category B biologic terrorism agent and the causative organism for melioidosis, which is endemic to certain tropical areas. Because laboratory workers had manipulated cultures of the organism, CDC was asked to assist in the subsequent investigation. This report summarizes the results of that investigation, which included assessment of laboratory exposures, postexposure chemoprophylaxis, and serologic testing of exposed laboratory workers. The findings underscore the need to reinforce proper laboratory practices and the potential benefits of chemoprophylaxis after laboratory exposures. The specimens were taken from a man aged 47 years with diabetes mellitus who had been evaluated at a local emergency department (ED) for fever, chills, and chest and leg pain. He had traveled to El Salvador 3 weeks earlier and returned 3 days before visiting the ED. During the preceding 2 weeks, the man had intermittent fever and night sweats. In the ED, a chest radiograph revealed bilateral and multifocal infiltrates, and he was admitted to the hospital; a computed tomography imaging scan indicated the presence of pulmonary abscesses. During the next 2 days, his condition deteriorated, requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure; he died from fulminant sepsis and multiorgan system failure. An autopsy revealed acute necrotizing pneumonia, multiple renal abscesses, and cirrhosis. During the patient's hospitalization, seven specimens of blood, urine, sputum, and bodily fluid were obtained; 2 days after the patient's death, bacterial isolates from all specimens were presumptively identified as B. pseudomallei by the laboratory's automated identification system and subsequently confirmed by polymerase chain reaction at the LACDHS Public Health Laboratory. A total of 17 laboratory workers had manipulated cultures from these specimens. These workers were considered exposed and were offered antibiotic chemoprophylaxis within 48 hours of their exposures. An onsite investigation was conducted on August 7. Laboratory procedures were reviewed and work activities classified into high and low risk. High-risk activities were defined as those that might result in organism-containing aerosol or droplet formation. High-risk activities included sniffing open culture plates to detect characteristic odors emitted by certain bacteria and preparing suspensions from culture plates using a vortex machine. High-risk activities also included routine laboratory procedures when not performed in a biological safety cabinet (BSC), such as picking colonies, subculturing, inoculating biochemical tests, centrifuging, and preparing slides. Manipulations of cultures inside a BSC were classified as low-risk exposures. On August 11, exposed workers completed a questionnaire regarding demographics, medical and travel histories, and work activities performed on the B. pseudomallei cultures. Active surveillance was conducted for symptoms consistent with melioidosis among exposed workers. Finally, serum specimens were obtained for anti-B. pseudomallei antibody testing from all exposed workers at 1, 2, 4, and 6 weeks after exposure. Serologic testing was performed by using an indirect hemagglutination test at PathCentre (Nedlands, Australia), with a positive result defined as a titer >40 (1). All 17 exposed workers completed the questionnaire. The median age was 48 years (range: 36--59 years). All reported >10 years of laboratory work experience (Table). Five persons (29%) reported an underlying condition, such as diabetes, that might put them at risk for severe disease. Eight (47%) reported having traveled to Southeast Asia during their lifetimes. Thirteen (77%) reported high-risk activities, including four (24%) who reported sniffing an open B. pseudomallei culture plate because of the distinctive "earthy" odor. Sixteen workers completed a 3-week regimen of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and one completed a 3-week regimen of doxycycline. Antibiotics were begun at a median of 2 days' postexposure (range: 0--4 days). None of the exposed laboratory workers had symptoms consistent with melioidosis during 5 months after exposure. Two laboratory workers had titers of <20 for B. pseudomallei on the first serum drawn. Both workers were born in the United States, and neither demonstrated an increase in titer 6 weeks after exposure. The first (no. 17) reported sniffing a B. pseudomallei culture plate. The worker recalled previous travel to Hawaii, Europe, Mexico, and Jamaica but reported no previous illnesses consistent with melioidosis. The second worker (no. 1) reported low-risk activities. The worker reported previous travel to the Philippines and Singapore and was hospitalized in 2001 for pneumonia with pleural effusions requiring thoracenteses; no pathogen was identified. Although the occurrence of potentially high-risk work activities performed outside a BSC were documented, no laboratory workers in this investigation were infected with B. pseudomallei. In response to this incident, laboratory safety recommendations for B. pseudomallei were reviewed; the laboratory had existing policies against sniffing all culture plates and continued to prohibit this and other unsafe laboratory practices. Reported by: BJ Currie, MD, Royal Darwin Hospital and Menzies School of Health Research, Darwin; TJ Inglis, MD, Western Australian Centre for Pathology and Medical Research (PathCentre), Nedlands, Australia. AM Vannier, MD, SM Novak-Weekley, PhD, Southern California Permanente Medical Group, Regional Reference Laboratories, Los Angeles; J Ruskin, MD, Kaiser Permanente Medical Center, Los Angeles; L Mascola, MD, E Bancroft, MD, L Borenstein, PhD, S Harvey, PhD, Los Angeles County Dept of Health Svcs, California. N Rosenstein, MD, TA Clark, MD, Div of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases; DM Nguyen, MD, EIS Officer, CDC. Editorial Note:This report describes the investigation into the exposure of 17 laboratory workers to the gram-negative bacillus B. pseudomallei, which causes melioidosis infection. The majority of infections with B. pseudomallei are asymptomatic (1). Symptomatic disease can be in localized or septicemic forms. Foci of infection include lung, skin, and genitourinary tract. Although infection can occur in healthy persons, B. pseudomallei is an opportunistic pathogen. Underlying immunosuppressing conditions, including diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, and alcohol abuse, are risk factors for septicemic melioidosis. Hypotension, absence of fever, leucopenia, and abnormal renal and hepatic function are poor prognostic features (2). B. pseudomallei is endemic to Southeast Asia and northern Australia, but sporadic cases have been reported from other tropical and subtropical areas between 20º north and south latitudes, including El Salvador (3). The primary route of infection is thought to be inoculation; however, infection might occur through inhalation, aspiration, and ingestion. The environmental reservoirs for B. pseudomallei are surface water and soil (4). The median incubation period of melioidosis is 9 days (range: 1--21 days), although reactivation of previously asymptomatic disease can occur after months or years (5). Two laboratory-acquired infections have been reported previously (6,7). A case of pneumonia, epididymo-orchitis, and a leg abscess occurred in a previously healthy laboratory worker. These conditions were associated with open-flask sonication of a suspension of organisms outside of a BSC, presumably resulting in inhalational exposure. In addition, a previously healthy bacteriologist had tender right axillary lymphadenopathy and pneumonia after cleaning a leaking centrifuge tube without wearing gloves. The worker reported having an ulcerative lesion on one finger at the time of the incident, suggesting that infection occurred via inoculation. After appropriate treatment, both patients recovered without adverse sequelae. Biosafety level (BSL) 2 practices, equipment, and containment are recommended for working with known or potentially infectious body fluids, tissue specimens, or cultures. However, a review of work in a clinical laboratory in an area in which melioidosis is endemic indicated low risk to laboratory workers (8). The laboratory described in that report followed BSL-2 precautions, with aerosol-generating procedures performed in a Class II or higher BSC, whereas new or ongoing cultures were examined on the open bench; sniff testing of opened culture plates was prohibited. Serologic follow-up of 60 laboratory workers over 15 years identified three workers with titers suggestive of subclinical infection, consistent with the background seroprevalence in the local community. These data suggest that infection is not easily acquired from routine, open-bench laboratory work with B. pseudomallei. In the current investigation, the low titers of workers no. 1 and 17 are not considered evidence of infection with B. pseudomallei among persons residing in areas where disease is not endemic (B. Currie, M.D., Royal Darwin Hospital and Menzies School of Health Research, personal communication, 2004). Recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or doxycycline for 3 weeks were based on in vitro and animal data; no published data for humans are available. Current treatment recommendations for melioidosis comprise an initial, intensive phase followed by eradication therapy (Box) (4). As the findings in this report indicate, potentially unsafe laboratory practices such as sniffing opened culture plates can occur before isolates are identified. Such practices should be prohibited, especially given that B. pseudomallei can be misidentified by biochemical substrate utilization tests (9). Because infection with B. pseudomallei can be severe, PEP with doxycycline (2 mg/kg up to 100 mg orally, twice daily) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (8 + 40 mg/kg up to 320 + 1,600 mg orally, twice daily) can be considered if cultures of the organism are inadvertently manipulated outside of BSL-2 conditions. Animal data suggest that 5 days of PEP might be insufficient to prevent infection (10). Because the incubation period of melioidosis can last up to 21 days, 3 weeks of PEP might be necessary. PEP should be recommended for laboratory manipulations or incidents that result in exposure to aerosols or droplets or contact with nonintact skin and for persons with risk factors for septicemic disease. CDC requests that incidents involving unsafe laboratory exposure to B. pseudomallei be reported to the Meningitis and Special Pathogens Branch, National Center for Infectious Diseases, telephone 404-639-3158. Acknowledgments The findings in this report are based, in part, on contributions by the Div of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, PathCentre, Nedlands, Australia. Epidemic Investigations Laboratory, CDC. References

Table  Return to top. Box  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 10/28/2004 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 10/28/2004

|