|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

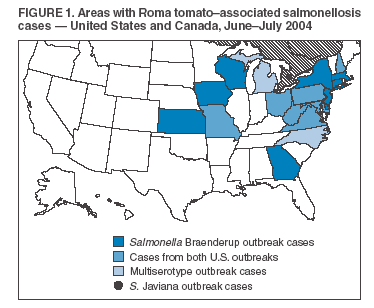

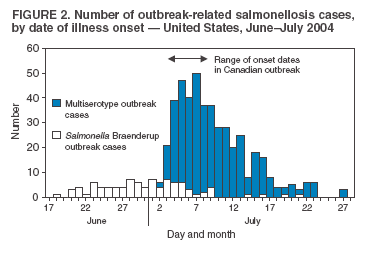

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Outbreaks of Salmonella Infections Associated with Eating Roma Tomatoes ---United States and Canada, 2004Three outbreaks of Salmonella infections associated with eating Roma tomatoes were detected in the United States and Canada in the summer of 2004. In one multistate U.S. outbreak during June 25--July 18, multiple Salmonella serotypes were isolated, and cases were associated with exposure to Roma tomatoes from multiple locations of a chain delicatessen. Each of the other two outbreaks was characterized by a single Salmonella serotype: Braenderup in one multistate outbreak and Javiana in an outbreak in Canada. In the three outbreaks, 561 outbreak-related illnesses from 18 states (Figure 1) and one province in Canada were identified. This report describes the subsequent investigations by public health and food safety agencies. Although a single tomato-packing house in Florida was common to all three outbreaks, other growers or packers also might have supplied contaminated Roma tomatoes that resulted in some of the illnesses. Environmental investigations are continuing. Because current knowledge of mechanisms of tomato contamination and methods of eradication of Salmonella in fruit is inadequate to ensure produce safety, further research should be a priority for the agricultural industry, food safety agencies, and the public health community. Multiserotype Salmonella Outbreak --- MultistateIn July 2004, a total of 429 culture-confirmed, outbreak-associated salmonellosis cases were identified in nine states (Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, New Hampshire, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia); these cases occurred among persons eating at delicatessen chain A sites, with symptom onset during July 2--27(Figure 2). The median age of patients was 35 years (range: 1--81 years); 52% were male. No deaths occurred, but 30% of patients were hospitalized. These cases yielded Salmonella serotypes Javiana (383), Typhimurium (27), Anatum (five), Thompson (four), Muenchen (four), and Group D untypable (six). State and local health departments, in collaboration with CDC, conducted a case-control study, which included 53 case-patients and 53 well meal-companion controls. Of the 53 case-patients, 47 (90%) ate Roma tomatoes, compared with 24 (48%) of the controls. Multivariate analysis data demonstrated a strong association with consumption of Roma tomatoes (adjusted odds ratio = 7.1; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.5--34). Delicatessen chain A had purchased presliced Roma tomatoes from a single processor for all of its 302 stores in five states. S. Anatum, with a pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) pattern indistinguishable from that of five cases in four states, was isolated from presliced Roma tomatoes sampled at a delicatessen chain A site on July 13. Roma tomatoes were removed from all delicatessen chain A sites on July 14. A total of 22 (5%) patients reported illness onset after July 19, outside the incubation period for Salmonella. These illnesses might be explained by factors such as continued Roma tomato use, poor recall, low infectious dose, food saved and eaten later, or secondary transmission. S. Braenderup Outbreak --- MultistateIn the summer of 2004, a total of 125 confirmed cases of S. Braenderup infection with an indistinguishable PFGE pattern were identified from 16 states (Delaware, Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wisconsin); patients had illness onset during June 18--July 21. The median age of patients was 30 years (range: 0--84 years); 66% were female. No deaths occurred, but 20% of patients were hospitalized. State and local health departments, in collaboration with CDC, conducted a case-control study among persons aged 15--60 years. A case was defined as infection with S. Braenderup yielding the outbreak PFGE pattern, with illness onset after June 15. Controls were enrolled through sequential-digit telephone dialing by using patients' area codes. A total of 38 case-patients and 79 controls were included. Patients were more likely than controls to have eaten out multiple times during the 5 days preceding illness onset (53% versus 34%) (odds ratio [OR] = 2.1; CI = 1.0--4.7). A higher proportion of patients than controls ate cheese, lettuce, and tomatoes outside the home, but these differences were not statistically significant. Using meal information from 27 case-patients and 29 controls, restaurant managers were asked about specific types of cheese, lettuce, and tomatoes used in dishes eaten by customers. Roma tomatoes, which were eaten by 41% of case-patients but only 14% of controls (OR = 4.1; CI = 1.1--15.3), were the only exposure significantly associated with illness. These restaurants purchased whole Roma tomatoes from tomato distributors. S. Javiana Outbreak --- CanadaSeven confirmed cases of S. Javiana infections with indistinguishable PFGE patterns, but with patterns distinct from the multiserotype Salmonella outbreak, were identified from one Canadian province, Ontario; illness onset occurred during July 4--8, 2004. The median age of ill persons was 28 years (range: 23--36 years). No deaths were reported, but 14% of persons were hospitalized. All patients ate at the same restaurant. Although a case-control study was not conducted, Roma tomatoes were the suspected outbreak vehicle because Roma tomatoes were the only common food exposure among all patients. Traceback and Environmental InvestigationThe Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in conjunction with state and provincial food regulatory agencies and state health departments, conducted traceback investigations of the Roma tomatoes eaten by patients in all three outbreaks. For each outbreak, Roma tomatoes were traced from restaurants back to distributors, packers, or growers in the United States. Traceback investigation of tomatoes from the multiserotype outbreak identified one field-packing operation and three packing houses from three states as possible sources. Of these four sources, Florida packing house A was also identified as a possible source for the two other concurrent Roma tomato--associated salmonellosis outbreaks (i.e., the S. Braenderup and S. Javiana outbreaks). Quality-control procedures at the tomato-slicing facility associated with the multiserotype Salmonella outbreak were inspected while the facility was in active operation; no source of contamination was identified. In addition, S. Javiana is typically associated with the coastal Southeast, whereas the slicing facility is located in the Northeast. Environmental investigation of four packers and five associated farms in Florida and South Carolina during August--November 2004 did not reveal a clear source of contamination, and the packing houses appeared to be following food-safety guidance. However, of these nine facilities, only Florida packing house A and one associated farm were in active operation at the time of inspection. Investigations will continue during the corresponding 2005 growing season. Reported by: R Corby, V Lanni, Brant County Health Unit, Ontario, Canada. V Kistler, MEd, Allentown Health Bur; V Dato, MD, A Weltman, MD, C Yozviak, K Waller, MD, K Nalluswami, MD, M Moll, MD, Pennsylvania Dept of Health. Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition; Office of Crisis Management, Food and Drug Admin. J Lockett, S Montgomery, DVM, M Lynch, MD, C Braden, MD, Div of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases; SK Gupta, MD, A DuBois, MD, EIS officers, CDC. Editorial Note:Tomatoes originated in South America, were introduced into Europe in the 16th century, and are now a popular food worldwide. The Roma tomato was developed in the mid-1950s as a firmer and more disease-resistant variety (1). Uncooked tomatoes have become an integral and nutritious component of the daily diet. Approximately 5 billion pounds of fresh market tomatoes are eaten annually in the United States, and thus the potential for large outbreaks of Salmonella infections is a concern. This report describes three outbreaks in the United States and Canada in which Roma tomatoes were implicated; as a result of these outbreaks, 2004 had the highest number of recorded annual tomato-associated Salmonella infections. In the eastern United States, tomatoes are grown in natural habitats for many known Salmonella reservoirs, including birds, amphibians, and reptiles. Salmonella infections have been linked to tomatoes since 1990, when S. Javiana caused 176 illnesses in four midwestern states (2). Those tomatoes, and those implicated in a subsequent outbreak in 1993, were traced to a South Carolina packing house. Cross-contamination might have occurred at the packing house, where substantial numbers of tomatoes passed through a common wash tank (2). In 1994 and 1995, a Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points program was implemented at this packing house and disseminated to the tomato industry (3). The key critical-control point implemented was maintenance of water quality, specifically monitoring chlorine levels, pH, and water temperature in the wash tank. Of seven subsequent tomato-associated Salmonella outbreaks, six have been traced to other packing houses in the southeastern United States (4,5). Although produce packing houses are specifically exempt from the requirements of Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs), FDA guidance (6) to the produce industry encourages GMP controls for water used in packing houses. However, the extent to which FDA guidance has been adopted by the industry is unknown. Tomato-associated Salmonella outbreaks reported to CDC have increased in frequency and magnitude in recent years and caused 1,616 reported illnesses in nine outbreaks during 1990--2004, representing approximately 60,000 illnesses when accounting for the estimated proportion (97.5%) of unreported illness (7). Salmonella can enter tomato plants through roots or flowers (8) and can enter the tomato fruit through small cracks in the skin, the stem scar, or the plant itself (9). However, whether Salmonella can travel from roots to the fruit, or if seeds can contaminate subsequent generations of tomato plants, is unknown. Understanding the mechanism of contamination and amplification of contamination of large volumes of tomatoes is critical to prevent large-scale, tomato-associated outbreaks. Contamination might occur during multiple steps from the tomato seed nursery to the final kitchen. Eradication of Salmonella from the interior of the tomato is difficult without cooking, even if treated with highly concentrated chlorine solution (10). Public health professionals should be aware of tomatoes as a possible vehicle when investigating Salmonella outbreaks. Current knowledge of mechanisms of tomato contamination and methods of eradication of Salmonella in fruit are inadequate to fully define interventions that will ensure produce safety. Studies into these concerns should be a priority for the agricultural industry, food safety agencies, and the public health community. Acknowledgments The findings in this report are based, in part, on contributions by state public health departments in Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. M Hoekstra, M Balasegaram, M Perch, C Snider, Div of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases; D Burmeister, EIS Officer, CDC. References

Figure 1  Return to top. Figure 2  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 4/7/2005 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 4/7/2005

|