|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

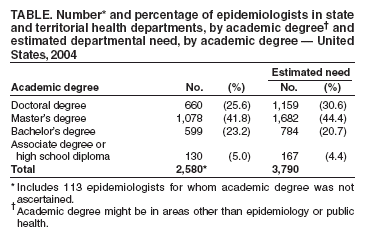

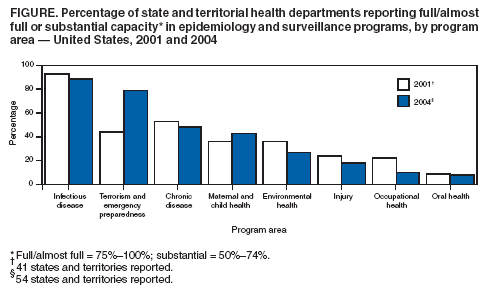

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Assessment of Epidemiologic Capacity in State and Territorial Health Departments --- United States, 2004In November 2001, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) conducted a survey of state and territorial health departments to assess their core epidemiologic capacity (1,2). The survey was completed just before distribution of approximately $1 billion in terrorism preparedness and emergency response funds in fiscal year 2002, intended to improve the U.S. public health infrastructure (3). Results of the 2001 survey, published in 2003, indicated inadequate capacity in six of eight key epidemiology program areas (all except infectious disease and chronic disease) to fully perform the essential public health services most dependent on epidemiology (1,4). In 2004, CSTE conducted a follow-up survey that assessed epidemiologic capacity in the United States and its territories in the same eight program areas, estimated the number of additional epidemiologists needed for full performance, and identified education and training needs (5). This report summarizes the results of that 2004 follow-up survey, which indicated a 26.9% increase* from 2001 in the overall number of epidemiologists working in state and territorial health departments, increased capacity in two program areas (i.e., terrorism preparedness and emergency response; maternal and child health) and decreased capacity in six other program areas (i.e., infectious disease, chronic disease, environmental health, injury, occupational health, and oral health) (2). Results also revealed that 28.5% of epidemiologists lacked any formal training or academic coursework in epidemiology. Creation of a strong public health infrastructure fully capable of performing essential services will require additional trained epidemiologists in state and territorial health departments. The CSTE survey was pilot tested in five states (Florida, Michigan, New York, North Carolina, and Tennessee) during April--May 2004 and made available online to all state and territorial health departments during May--September 2004. State epidemiologists or their designees provided information for the survey. Participants included representatives of all 50 states, three of eight territories (37.5%), and the District of Columbia, for an overall response rate of 91.5%. The definition of epidemiologist was unchanged from the 2001 survey, although further clarification was provided regarding who should be counted as an epidemiologist in a state or territorial health department in the 2004 assessment†. If epidemiologists divided their time between two program areas, increments of 0.5 full-time equivalent were allocated to each program area. In 2004, a total of 2,580 epidemiologists were reported working in state and territorial health departments; survey participants estimated that a total of 3,790 epidemiologists (an increase of 47%) were needed to fully address the essential services of public health most dependent on epidemiology (Table). Participants reported that more epidemiologists were needed in all eight key program areas. The number of epidemiologists in each program area, the estimated number of additional epidemiologists needed to fully serve each program area, and the percentage increase needed were as follows: infectious disease (926 epidemiologists, 325 additional needed, 35.1% increase); chronic disease (390, 183, 46.9%); environmental health (324, 164, 50.6%), terrorism and emergency preparedness (424, 192, 45.3%), maternal and child health (239, 155, 64.9%), injury (74, 131, 177.0%), occupational health (51, 102, 200.0%), and oral health (39, 71, 182.1%). Participants were asked to assess epidemiologic and surveillance capacity in eight key program areas by using a six-point scale, which was converted to the four-point scale§ used in the 2001 assessment to enable comparison. Participants reported increased capacity from 2001 to 2004 in two program areas (i.e., terrorism preparedness and emergency response and maternal and child health) and decreased capacity in six other program areas (i.e., infectious disease, chronic disease, environmental health, injury, occupational health, and oral health) (Figure). The majority of state and territorial health departments reported full, almost full, or substantial capacity in only two program areas, infectious disease and terrorism preparedness and emergency response. In addition, respondents were asked to self-assess their abilities to provide the essential public health services most dependent on epidemiology (1,4). Among the 50 states, 31 (62.0%) reported having substantial-to-full capacity to monitor health status and solve community health problems, and 29 (58.0%) reported substantial-to-full capacity in diagnosing and investigating health problems and health hazards in the community. In contrast, 11 states (22.0%) reported having substantial-to-full capacity in evaluating effectiveness, accessibility, and quality of personal and population-based health services, and six states (12.0%) reported substantial-to-full capacity in researching for new insights and innovative solutions to health problems. The largest percentage of epidemiologists working in state and territorial health departments had master's degrees (41.8%), followed by doctoral degrees (25.6%), bachelor's degrees (23.2%), and associate degrees or high school diplomas (5.0%) (Table). Information on epidemiology training was obtained for 1,897 (73.5%) of the 2,580 epidemiologists. Of these 1,897, a total of 986 (51.9%) had degrees in epidemiology, and 369 (19.4%) had completed other formal training or academic coursework in epidemiology; 541 (28.5%) had no formal training or academic coursework in epidemiology. During the 12 months preceding the assessment, 48 of 51 (94.1%) respondents reported providing or funding training or education to enhance the competence of epidemiologists. Adequate training in epidemiology varied among state and territorial health departments. For example, 17 of 49 participants (34.7%) reported providing adequate training in evaluation of public health interventions, and 38 of 48 (79.2%) provided adequate training in outbreak investigation methodology. Needs for additional training were most often cited in the following areas: evaluation of public health interventions (42 of 45 [93.3%], designing epidemiologic studies (39 of 47 [83.0%]), leadership and management training (37 of 46 [80.4%]), analyzing and characterizing epidemiologic data with statistical software (36 of 45 [80.0%]), designing and evaluating surveillance systems (37 of 47 [78.7%]), and designing data collection tools to address a health problem (37 of 47 [78.7%]). Reported by: ML Boulton, MD, Univ of Michigan School of Public Health. J Abellera, MPH, J Lemmings, MPH, L Robinson, MPH, Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, Atlanta, Georgia. Editorial Note:The influx of approximately $1 billion in terrorism preparedness and emergency response funds substantially strengthened the epidemiologic capabilities of the public health structure in the United States. However, despite this increased funding, state and territorial health departments report that a 47% increase in the number of epidemiologists is needed to fully perform the nation's essential public health services most dependent on epidemiology. In 2003, CSTE recommended that 80% of the state and territorial epidemiology workforce should have formal training in epidemiology. However, in 2004, 48.0% of epidemiologists in state and territorial health departments had no academic degree in epidemiology, and 28.5% had no formal training or academic coursework in epidemiology. Further attention to recruitment and training are needed to increase the number of trained epidemiologists and improve the public health infrastructure in the United States. The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, 38 states participated in the 2001 survey, compared with 50 in the 2004 survey, affecting comparability of results. Second, methods used by respondents to estimate the number of epidemiologists needed for their departments to perform essential public health services and to estimate epidemiologic capacity likely varied. In 1988, and again in 2002, the Institute of Medicine recommended that every public health department regularly and systematically collect, assemble, analyze, and make available information regarding the health of the community, including statistics on health status, community health needs, and epidemiologic and other studies of health problems (7,8). The threat of terrorism renewed calls for strengthening the public health infrastructure. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has emphasized the need for a closely linked, nationwide public health network of local, regional, and state health resources (4). Epidemiologists in state and territorial health departments are essential to the monitoring of chronic conditions and diseases and the rapid detection and reporting of infectious disease outbreaks, whether or not related to terrorism. New and better means for estimating the epidemiologic capacity needs and measuring the performance of state and territorial health departments should continue to be created. CDC and CSTE are in the process of defining core competencies for epidemiologists, which should facilitate staffing and development of training. In the meantime, the findings from the 2004 epidemiologic capacity survey, with the limitations noted, can serve as a useful baseline for future epidemiologic assessments. References

* The 2004 CSTE epidemiology capacity assessment determined that 2,580 epidemiologists were working in state and territorial health departments compared with 1,366 in 2001, an increase of 89%. However, the number and percentage of states and territories responding to the 2004 survey were substantially higher than in 2001 (54 [91.5%] versus 44 [78.6%]) (1). Comparing only the District of Columbia and 38 states that participated in both surveys, the increase in epidemiologists was 343 (26.9%). † The definition of epidemiologist was from A Dictionary of Epidemiology (6). For the 2004 CSTE survey, epidemiologists in state and territorial health departments were defined as any persons who performed functions consistent with this definition, regardless of job title. § The six-point scale was as follows: Full = 100%, almost full = 75%--99%, substantial = 50%--74%, partial = 25%--49%, minimal = <25%, and none = 0. The four-point scale was as follows: Full/almost full = 75%--100%, substantial = 50%--74%, partial = 25%--49%, and minimal or no capacity = <25%. Table Return to top. Figure  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Date last reviewed: 5/12/2005 |

|||||||||

|