|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

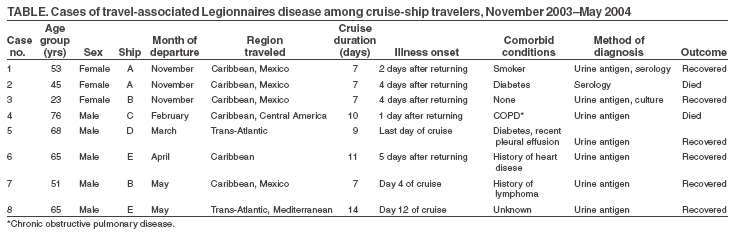

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Cruise-Ship--Associated Legionnaires Disease, November 2003--May 2004More than 9.4 million passengers traveled on pleasure cruises departing from North American ports in 2004, an increase of 13% since 2003 and 41% since 2001 (1). Cruise ships typically transport closed populations of thousands of persons, often from diverse parts of the world. Travelers are at risk for becoming ill while on board, most commonly from person-to-person spread of viral gastrointestinal illnesses. Certain environmental organisms, such as Legionella spp., pose a risk to vulnerable passengers. During November 2003--May 2004, eight cases of Legionnaires disease (LD) among persons who had recently traveled on cruise ships were reported to CDC. This report describes these cases to raise clinician awareness of the potential for cruise-ship--associated LD and to emphasize the need for identification and reporting of cases to facilitate investigation. LD is a severe community-- or health-care--associated pneumonia caused by Legionella spp., most commonly L. pneumophila. LD can result from inhalation or aspiration of warm (25°C--42°C), aerosolized water containing Legionella. Symptoms typically begin 2--10 days after exposure. Person-to-person transmission does not occur. Because symptoms of LD (e.g., fever, cough, or chest pain) are nonspecific, LD cannot be reliably distinguished from other forms of pneumonia on the basis of clinical presentation alone. In the United States, LD can be reported to CDC through two surveillance systems. The National Electronic Telecommunications System for Surveillance collects information on all reportable diseases from state and territorial health departments but does not collect information on travel history. In contrast, the paper-based Legionnaires Disease Reporting System collects details of any recent travel from LD patients but receives data on only a fraction of the total cases estimated to occur. The cases described in this report were initially relayed to CDC by direct communication from state health departments, cruise lines, and the European Working Group for Legionella Infections (EWGLI), which operates a surveillance scheme (EWGLINET) for LD among European travelers (http://www.ewgli.org). Cases were defined as laboratory-confirmed LD in a person with cruise-ship travel during the 10 days before symptom onset. Exposure history was collected by the state and local health departments, and environmental samples, when obtained, were tested by contractors hired by the cruise lines. The eight cases were among passengers who had been aboard five different cruise ships and associated with seven different voyages (Table). Two of the eight cases occurred on the same voyage. The mean age of the patients was 55.8 years (range: 23--76 years). Five (63%) were male; seven (88%) were U.S. residents. The sole case in a foreign traveler occurred in a Dutch woman aged 23 years who had onset of fever and cough 4 days after returning from a cruise in the Caribbean. Two (25%) cases were fatal. Of the seven patients with known medical histories, six (86%) had comorbidities or risk behaviors known to be risk factors for LD (e.g., diabetes, history of heart disease, or smoking) (Table). The mean time from cruise-ship boarding to onset of symptoms was 10.4 days (range: 4--16 days). Although two passengers had symptoms before the end of their respective cruises, only one had LD diagnosed while still aboard the ship. Seven (88%) were diagnosed by urinary antigen testing for Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 (Lp1). The only person with LD diagnosed by a fourfold increase in anti-Legionella spp. serology had a negative Legionella urinary antigen test. Only the Dutch traveler had a culture for Legionella obtained at the onset of illness. The culture was positive for Lp1; a urinary antigen test also was positive. Two cases occurred on each of three cruise ships. Two patients were aboard the same ship during the same period but had been friends preceding the cruise and therefore had other exposures in common. A definite source of exposure could not be identified for any of the cases because of the limited number of cases. In addition, all but one patient lacked a clinical isolate, limiting the ability to link clinical and environmental isolates. For the Dutch passenger, the sole patient with a clinical isolate, environmental sampling was performed, but no matching environmental isolate was identified. Additional case-finding measures included review of infirmary records by cruise lines and CDC, passive surveillance by cruise lines, public health alerts via the Epidemic Information Exchange (Epi-X), and notifications to EWGLI in the event vacationing European travelers had become ill. Despite these activities, no other cases were identified. Reported by: C Joseph, DrPH, EWGLINET, London, England. J van Wijngaarden, MD, Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport. P Mshar, MPH, Connecticut Dept of Health. C Oravetz, Flagler County Health Dept, Bunnell, Florida; AM Fix, MPH, Florida Dept of Health. CA Genese, MBA, New Jersey Dept of Health and Senior Svcs. GS Johnson, M Kacica, MD, New York State Dept of Health. B Weant, Guilford County Dept of Public Health, Greensboro, North Carolina; P Jenkins, EdD, North Carolina Dept of Health and Human Svcs. N Baker, MPH, Philadelphia Dept of Health. D Forney, J Ames, MPH, G Vaughan, MPH, Jon Schnoor, Vessel Sanitation Program, National Center for Environmental Health; D Kim, MD, M Guerra, DVM, Div of Global Migration and Quarantine; B Fields, PhD, M Moore, MD, Div of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases; C Newbern, PhD, M Thigpen, MD, EIS officers, CDC. Editorial Note:During 1980--1998, CDC received an average of 360 paper-based reports of LD annually, primarily during summer months (2). However, previous research using population-based active surveillance estimated that 8,000--18,000 cases of Legionella spp. infection requiring hospitalization occur in the United States annually, suggesting that legionellosis is underdiagnosed and/or underreported (3). Since the first recognized outbreak of LD occurred in 1976 among persons attending the American Legion convention in Philadelphia, travel has been identified as a risk factor for both outbreak-associated (4) and sporadic infection (5). However, for multiple reasons, outbreaks of travel-associated legionellosis are difficult to detect and investigate (6,7). First, trends toward empirical use of antimicrobial agents have led to declines in diagnostic testing for etiologic agents of community-acquired pneumonia (8). Second, the incubation period of 2--10 days allows travelers to return home before they have symptoms, making it unlikely for a medical provider to see more than a single case. Third, because LD can be diagnosed within hours of specimen collection by urine antigen testing, diagnosis by culture, which requires several days, has declined substantially in recent years (2). The lack of clinical isolates hinders epidemiologic investigations and prevention strategies. Legionella spp. can be identified by culture in up to 40% of freshwater environmental samples and in up to 80% of environmental samples by polymerase chain reaction (9). Although Lp1 causes approximately 70% of cases, at least 22 species of Legionella have been associated with disease in humans (9). To determine which of many potential environmental Legionella spp. is the causative organism, a clinical isolate from a respiratory culture must be matched to the environmental isolate by monoclonal antibody subtyping or by molecular methods. For these reasons, when evaluating a patient with suspected LD, clinicians should obtain a travel history and collect respiratory secretions for culture, in addition to collecting urine for antigen testing. Reporting of LD is mandatory in every state. However, dispersion of travelers to multiple states after an exposure might result in a health department receiving only one report in association with a particular ship or hotel. Cruise-ship-- associated travel poses additional difficulties for notification and investigation of LD cases. For cruise ships that sail in international waters, patients might be hospitalized in other countries, delaying or precluding reporting to authorities in the patients' home countries. Because travelers often stay in hotels before or after cruise-ship travel and often disembark at various international ports of call during a cruise, numerous potential sources exist for authorities to investigate. In certain instances, cruise-ship travel might be of insufficient duration (e.g., a single day or overnight trip) to be inclusive of the 2--10-day incubation period of LD. In addition, the limited number of reported cases associated with cruises limits the ability of traditional epidemiologic methods to identify a source. Thus, the task of identifying a source often relies on matching a clinical isolate to an environmental isolate. However, few cases have been reported for which an environmental isolate identified from a cruise ship (most often from a whirlpool spa) was identical to a clinical isolate from an ill passenger (6,7). Obtaining a clinical isolate from a patient with travel-associated LD is essential to identifying the source of infection. Public health programs have focused on reducing the risk for LD among cruise-ship passengers. In 1994, CDC investigated an LD outbreak on board a cruise ship and subsequently issued recommendations to reduce transmission of Legionella spp. from shipboard whirlpool spas. (10). In addition, CDC's Vessel Sanitation Program regularly conducts inspections of these spas and other environmental sources. Given the difficulties in confirming cases of LD, cooperation of clinicians and local, national, and international public health agencies is essential to foster diagnosis and prevention. Because a single case of LD in a traveler might indicate an outbreak, prompt recognition and direct reporting to local, state, and federal officials can prevent additional cases of travel-associated illness. References

Table  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Date last reviewed: 11/17/2005 |

|||||||||

|