Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Pediatric Bacterial Meningitis Surveillance --- African Region, 2002--2008

Sub-Saharan Africa has one of the world's greatest disease burdens of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Neisseria meningitidis infections. In 2000, Hib and S. pneumoniae infections accounted for approximately 500,000 deaths in the region (1); during the past 10 years, N. meningitidis has been responsible for recurring epidemics resulting in approximately 700,000 cases of meningitis.* Introduction of vaccines against bacterial pathogens in Africa has been constrained by competing public health priorities, limited availability of Hib and S. pneumoniae vaccines, suboptimal N. meningitidis vaccine, inadequate funding, and limited information regarding the disease burden associated with these infections (2,3). The World Health Organization (WHO) and CDC analyzed data for 2002--2008 from the Pediatric Bacterial Meningitis (PBM) Surveillance Network, which collects information on laboratory-confirmed bacterial meningitis cases among children aged <5 years at sentinel hospitals in countries throughout the WHO African Region. The results of that analysis determined that, during 2002--2008, a total of 74,515 suspected cases of meningitis were reported. Among the 69,208 suspected cases with known laboratory results, 4,674 (7%) samples were culture-positive for the three bacterial infections under surveillance: 2,192 (47%) were positive for S. pneumoniae, 1,575 (34%) for Haemophilus influenzae, and 907 (19%) for N. meningitidis. The majority of the remaining culture results were negative. These and other PBM network findings will help guide strategies for strengthening laboratory and data management capacity at existing sentinel hospitals and for planning future network expansion in the WHO African Region.

PBM Surveillance Network

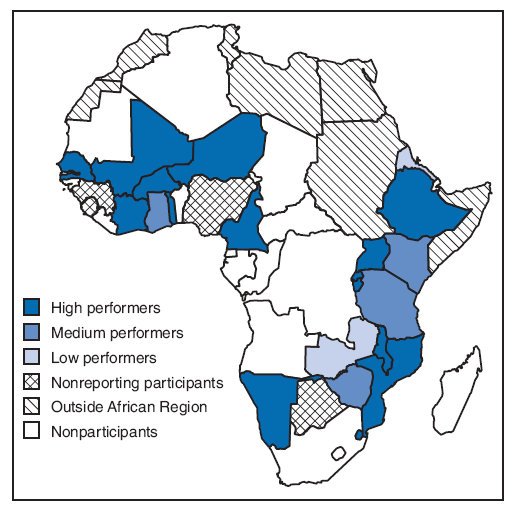

WHO and global immunization partners launched the PBM network in the WHO African Region in 2001. During 2001--2002, clinical, laboratory, and data management staffs in 26 of the 46 countries in the African Region were trained to conduct hospital-based PBM sentinel surveillance. In 2008, 22 countries continued to participate in the network (Figure). Initial country involvement was determined according to ministry of health interest in new vaccine introduction and commitment for conducting disease surveillance, eligibility for financial support from the GAVI Alliance,† and lack of resource conflicts (e.g., with polio eradication activities). Standardized surveillance guidelines were developed for identifying suspected meningitis cases, laboratory confirmation, and data reporting.§

Of the 22 countries reporting data in 2008, 18 had one sentinel site, and four had two or more sites. In 2003, Kenya, Uganda, and the United Republic of Tanzania expanded their national programs to include additional sentinel sites with support from the Network for Surveillance of Pneumococcal Disease in the East African Region (netSPEAR).¶ Including sites from netSPEAR, a total of 26 sentinel hospitals participated in the PBM network in 2008. Twenty-two (85%) of the sentinel sites were located at national referral or teaching pediatric hospitals in major urban centers with on-site laboratory capacity to identify bacterial pathogens.

The coordination and implementation of surveillance activities are conducted at the country level collaboratively by the ministry of health and WHO staff and at the regional level by WHO. Sentinel hospital teams include clinical, laboratory, and data management staff members. At each site, all children aged 0--59 months with an illness meeting the standardized case definition for meningitis** are reported as suspected cases, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) specimens are collected and cultured for bacterial infection. H. influenzae isolates are not serotyped routinely and are assumed to be type b based on previous evidence suggesting that >90% of H. influenzae isolates before vaccine introduction are type b (4). Case data are analyzed locally and then forwarded to ministries of health and country and regional WHO offices.

Surveillance Performance

Four clinical and laboratory indicators were developed to assess the performance of the network in each country.†† In 2001, the number of participating countries reporting was 26; in 2003 the number was 24, and in 2008, 22. In 2002, the first full year after training, three (14%) of the 23 participating countries were high performers (meeting three or more indicators), four (18%) were medium performers (meeting two or more indicators), and 16 (70%) were low performers (meeting one or fewer indicators). In 2008, of the 22 countries reporting to the network, 14 (64%) were high performers, six (27%) were medium performers, and two (9%) were poor performers.

Network Findings

During 2002--2008, a total of 74,515 cases of suspected bacterial meningitis were reported to the PBM network (Table). Of these, 72,111 (97%) had a lumbar puncture performed, and 69,208 (96%) had CSF results logged into the database. Of those with known CSF results, 4,674 (7%) were culture-positive for the three bacterial infections under surveillance: 2,192 (47%) for S. pneumoniae, 1,575 (34%) for H. influenzae, and 907 (19%) for N. meningitidis. The majority of the remaining 64,534 CSF results logged into the database were culture-negative, including 5,453 (54%) of the 10,127 purulent specimens (i.e., those with turbid appearance or ≥100 white blood cells/mm3) (5).

Integration with Rotavirus Surveillance

Of the 14 countries in the African Region conducting sentinel site surveillance for rotavirus diarrhea, nine (64%) have integrated rotavirus diarrhea surveillance activities with PBM surveillance. Areas of integration include 1) case identification through shared hospital sentinel site staffing, 2) data reporting (integrated data management tools) and feedback mechanisms from WHO regional office to country and sentinel site staff, and 3) use of laboratory equipment and technicians for performing diagnostic procedures.

Reported by: B Mhlanga, MD, R Katsande, Dept of Immunization, Vaccines, and Biologicals, African Regional Office, Harare, Zimbabwe; CM Toscano, MD, PhD, T Cherian, MD, Dept of Immunization, Vaccines, and Biologicals, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. R O'Loughlin, PhD, London School of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. J Rainey, PhD, T Hyde, MD, Global Immunization Div, AL Cohen, MD, Div of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC.

Editorial Note:

The PBM Network was launched to provide participating countries with local data that might aid in decisions regarding introduction of new vaccines against bacterial infections. Gambia introduced Hib vaccine in 1993; 18 other countries with staffs trained to conduct PBM surveillance in the African Region introduced Hib vaccine by the end of 2008§§ (2). PBM network countries will be considering introduction of pneumococcal vaccine with support from the GAVI Alliance during the next few years¶¶ (3); countries in the meningococcal epidemic-prone regions of Sub-Saharan Africa also will be considering the new serogroup A conjugate meningococcal vaccine when available.*** Although reporting quality varied during 2002--2008, the network generated data on the epidemiology of H. influenzae that was useful in some countries for making decisions regarding the introduction and sustained use of Hib vaccine. In these countries, data provided information on trends in H. influenzae and purulent meningitis and the effectiveness of Hib vaccine against bacterial meningitis (6--8; Agence de Medecine Preventive, unpublished data, 2008). High performing countries might be capable of producing similar data for S. pneumoniae and N. meningitidis infections, but the majority of PBM network countries will require additional support and training before PBM data can be fully utilized for interpreting disease trends and assessing the impact of Hib, pneumococcal, and meningococcal vaccines.

This analysis identified a number of current limitations with the interpretations of the PBM surveillance data, some of which are related to country performance. Poor performance among network countries was most frequently related to reporting <8 months of surveillance data per year and a lower than expected number of culture-positive meningitis cases, two of the four performance indictors. Failure to attain these indicators can be attributed to high staff turnover, inconsistent adherence to standardized operating guidelines, and a diminishing prioritization for surveillance in some countries after successful Hib vaccine introduction. Many of the PBM sentinel hospitals lacked necessary laboratory reagents, and patients often received antibiotics before arriving at the sentinel hospital, greatly diminishing the sensitivity of CSF cultures and likely contributing to the low culture yields for the three bacterial infections under surveillance and the high percentage of purulent but culture-negative CSF specimens.

Conducting sentinel surveillance only in pediatric referral hospitals has additional limitations, including the possibility of failing to detect disease because of 1) referral practices, 2) pretreatment with antibiotics, 3) being unable to identify epidemic diseases such as meningococcal disease that might occur in rural communities located far from the PBM sentinel hospital sites. Furthermore, sentinel surveillance frequently is unable to generate disease burden estimate or provide national or regional serotype distribution of bacterial infections under surveillance.

To improve surveillance quality, especially rates of pathogen isolation, an accreditation system tailored for network laboratories is needed. Reference laboratories in each of the three African subregions will be required to ensure high quality surveillance data for confirmation and serotyping of bacterial pathogens, especially following pneumococcal vaccine introduction. These reference laboratories can complement the External Quality Assurance program††† initially introduced for the region's Public Health Laboratories and now expanded to include the PBM network. Efforts to establish a procurement system for supplying standardized laboratory supplies and reagents for PBM surveillance activities are likely to improve pathogen isolation rates at all sites. Introduction of polymerase chain reaction assays and other laboratory procedures also might increase the yield. Staffs in high performing countries also will require training in culturing blood specimens to better define the importance of S. pneumoniae pneumonia and sepsis-related disease in the region.

To obtain accurate information on disease burden, WHO's African Office is considering the feasibility of conducting active, population-based surveillance at a few sentinel sites. These sites will have pediatric population data for children served by the sentinel hospitals, and therefore, will be able to generate disease incidence for the three bacterial infections under surveillance. Additionally, WHO's African Regional Office is working with ministry of health staffs to identify prospective sentinel sites in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria. These two countries account for approximately 783 million persons, or 26% of the population in the African Region. Two or three participating sentinel hospitals in each of these countries will collect disease information from large pediatric populations that will contribute to understanding the epidemiology of meningitis in the region. Network expansion efforts should continue to identify and take advantage of linkages for integration in supporting surveillance for diseases prevented by other new vaccines such as rotavirus (9).

In launching PBM surveillance, the WHO African Regional Office in collaboration with global immunization partners has developed and promoted standardized guidelines, case definitions, laboratory protocols, and a uniform reporting mechanism; these are critical components for realizing a coordinated and long-term strategy for surveillance and immunization policy against invasive bacterial infections. Strengthening laboratory and data management capacity will be critical to ensure quality surveillance data in the future. Ultimately, the network's usefulness will depend on increasing local ownership of PBM surveillance, facilitating data use by ministries of health, and incorporating surveillance activities into national fiscal and program plans.

Acknowledgments

This report is based, in part, on the contributions of staff members of the Pediatric Bacterial Meningitis Surveillance Network and ministries of health in Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, Swaziland, Togo, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

References

- Peltola H. Worldwide Haemophilus influenzae type b disease at the beginning of the 21st century: global analysis of the disease burden 25 years after the use of the polysaccharide vaccine and a decade after the advent of conjugates. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000;13:302--17.

- CDC. Progress toward introduction of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine in low-income countries---worldwide, 2004--2007. MMWR 2008;57:148--51.

- CDC. Progress in introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine---worldwide, 2000--2008. MMWR 2008;57:1148--51.

- World Health Organization. Global literature review of Haemophilus influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae invasive disease among children less than five years of age 1980--2005. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2009/who_ivb_09.02_eng.pdf.

- Bennett JV, Platonov AE, Slack M, Mala P, Burton AH, Robertson SE. Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) meningitis in the pre-vaccine era: a global review of incidence, age distributions, and case-fatality rates. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Vaccines and Biologicals, World Health Organization; 2002. Available at http://www.who.int/vaccines-documents.

- Lewis RF, Kisakye A, Gessner B, et al. Action for child survival: elimination of Haemophilus influenzae type B meningitis in Uganda. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:292--301.

- Daza P, Banda R, Misoya K, et al. The impact of routine infant immunization with Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine in Malawi,

a country with high immunodeficiency virus prevalence. Vaccine 2006;24:

6232--9. - Muganga N, Uwimana J, Fidele N, at al. Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine impact against purulent meningitis in Rwanda. Vaccine 2007;25:7001--5.

- World Health Organization. Global framework for immunization monitoring and surveillance (GFIMS). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007.

* Additional information available at http://www.who.int/csr/disease/meningococcal/en/index.html.

† GAVI Alliance provides funding to support immunization activities and vaccine purchase in countries with annual gross national income per capita of <$1000. In 2008, 36 (78%) of 46 countries in the African Region were GAVI eligible.

§ Information available at http://afro.who.int/hib/manual/index.html.

¶ Information available at http://www.netspear.org.

** A child with sudden onset of fever and one or more of the following clinical symptoms or signs of meningitis: seizures other than febrile seizures, neck stiffness, bulging fontanel (in children aged <12 months), poor sucking, altered consciousness, irritability, other meningeal signs, toxic appearance, or petechial or purpuric rash.

†† 1) percentage of patients in clinically suspected cases who received a lumbar puncture (target: 80%), 2) percentage of lumbar punctures performed for which results were recorded in the database (target: 90%), 3) percentage of specimens of purulent cerebrospinal fluid that showed bacterial growth (target: 20%), and 4) number of months for which reports were made each year (target: ≥8 months); meeting this indicator is required to obtain a medium or high performance level. High performers met three or more indicators, medium performers met two indicators, and poor performers met one or fewer indicators.

§§ In addition to Gambia, countries that introduced Hib vaccine before the end of 2008 were Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

¶¶ Among the PBM network countries, Rwanda introduced pneumococcal vaccine in early 2009, Gambia is scheduled to introduce the vaccine in mid-2009, and Kenya has been approved by GAVI for introduction in 2010.

*** Epidemic-prone countries will be considering introduction of serogroup A conjugate meningococcal vaccine initially for use in mass vaccination campaigns in Africa. This vaccine has the advantage of inducing 1) immunity in young children, 2) long-term immunity, and 3) herd immunity. Information available at http://www.meningvax.org.

††† Information available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2007/who_cds_epr_lyo_2007.3_eng.pdf.

FIGURE. Countries trained to conduct surveillance for the Pediatric Bacterial Meningitis Surveillance Network, by performance level* --- World Health Organization African Region, 2008

* Based on four clinical and laboratory indicators: 1) percentage of patients in clinically suspected cases who received a lumbar puncture (target: 80%), 2) percentage of lumbar punctures performed for which results were recorded in the database (target: 90%), 3) percentage of specimens of purulent cerebrospinal fluid that showed bacterial growth (target: 20%), and 4) number of months for which reports were made each year (target: ≥8 months); meeting this indicator is required to obtain a medium or high performance level. High performers met three or more indicators, medium performers met two indicators, and poor performers met one or fewer indicators. High performers were Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Malawi, Mali, Namibia, Niger, Rwanda, Swaziland, Senegal, Togo, and Uganda. Medium performers were Kenya, Ghana, the United Republic of Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. Low performers were Eritrea, Gambia, and Zambia. Participating countries that did not report during 2008 were Benin, Botswana, Guinea, and Sierra Leone.

Alternative Text: The figure above shows countries trained to conduct surveillance for the Pediatric Bacterial Meningitis Surveillance Network, by performance level. During 2001-2002, clinical, laboratory, and data management staffs in 26 of the 46 countries in the African Region were trained to conduct hospital-based PBM sentinel surveillance. In 2008, 22 countries continued to participate in the network.

|

TABLE. Number and percentage of suspected* and confirmed cases of Haemophilus influenzae,† Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Neisseria meningitidis infections --- Pediatric Bacterial Meningitis Surveillance Network, World Health Organization African Region, 2002--2008 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

No. countries reporting |

No. suspected meningitis cases |

No. (%) suspected cases with lumbar puncture performed |

No. (%) suspected cases with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) result in database |

No. (%) CSF specimens purulent§ |

No. (%) CSF specimens culture-positive for H. influenzae, S. pneumoniae, or N. meningitidis |

No. (%)¶ CSF specimens culture-positive for S. pneumoniae |

No. (%)¶ CSF specimens culture-positive for H. influenzae |

No. (%)¶ CSF specimens culture-positive for N. meningitidis |

|

2002 |

23 |

6,715 |

6,380 (95) |

5,650 (89) |

1,151 (20) |

738 (13) |

336 (6) |

281 (5) |

121 (2) |

|

2003 |

24 |

12,397 |

12,043 (97) |

10,898 (90) |

1,880 (17) |

873 (8) |

440 (4) |

344 (3) |

89 (1) |

|

2004 |

23 |

12,341 |

11,762 (95) |

11,417 (97) |

1,733 (15) |

800 (7) |

392 (3) |

260 (2) |

148 (1) |

|

2005 |

24 |

14,583 |

14,089 (97) |

13,666 (97) |

1,942 (14) |

718 (5) |

346 (3) |

270 (2) |

102 (1) |

|

2006 |

23 |

10,780 |

10,533 (98) |

10,429 (99) |

1,320 (13) |

601 (6) |

295 (3) |

162 (2) |

144 (1) |

|

2007 |

23 |

8,847 |

8,721 (99) |

8,637 (99) |

1,075 (12) |

446 (5) |

204 (2) |

120 (1) |

122 (1) |

|

2008 |

22 |

8,852 |

8,583 (97) |

8,511 (99) |

1,026 (12) |

498 (6) |

179 (2) |

138 (2) |

181 (2) |

|

Total |

24 |

74,515 |

72,111 (97) |

69,208 (96) |

10,127 (15) |

4,674 (7) |

2,192 (3) |

1,575 (2) |

907 (1) |

|

* All children aged 0--59 months with an illness meeting the standardized case definition for meningitis were reported as suspected cases. Meningitis was defined as sudden onset of fever and one or more of the following clinical symptoms or signs of meningitis: seizures other than febrile seizures, neck stiffness, bulging fontanel (in children aged <12 months), poor sucking, altered consciousness, irritability, other meningeal signs, toxic appearance, or petechial or purpuric rash. † H. influenzae isolates were not routinely serotyped and are assumed to be type b based on previous evidence suggesting that >90% of H. influenzae isolates before vaccine introduction are type b. (World Health Organization. Global literature review of Haemophilus influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae invasive disease among children less than five years of age 1980--2005. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Vaccines and Biologicals, World Health Organization; 2009. Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2009/who_ivb_09.02_eng.pdf.) § Specimens classified as purulent if they had turbid appearance or a white blood cell count ≥100 cells/mm3. ¶ Percentage represents culture-positive specimens among all suspected cases with CSF results entered in the database. The majority of culture results were negative for pathogens other than the three under surveillance. |

|||||||||

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services. |

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Date last reviewed: 5/14/2009