Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Hurricane Ike Rapid Needs Assessment --- Houston, Texas, September 2008

On the morning of September 13, 2008, Hurricane Ike made landfall on the upper Texas Gulf coast at Galveston Island as a category 2 storm, with hurricane force winds extending 125 miles from its center (1). As the storm continued through nearby Houston and surrounding areas, it caused power blackouts for more than 3 million households. In Houston, city services were disrupted for weeks, officials declared nightly curfews, and supplies of bottled water, ice, electrical generators, and gasoline became scarce. At least five deaths were associated with carbon monoxide asphyxiation from improper use of generators in homes (2). During September 18--19, 2008, the Houston Department of Health and Human Services conducted a rapid needs assessment to gauge the prevalence of injuries and health complaints, determine immediate needs for health-care and medical supplies, and provide assessment information to those responsible for postdisaster response management and intervention. This report describes the assessment, which found that services to residents were disrupted longer and more extensively than anticipated, and that the greatest need among surveyed households was for assistance obtaining food (26.8%). The results suggest the need to prepare communities at risk for hurricanes for longer than the commonly anticipated 3--5 day recovery period. These findings also highlight the importance of rapid assessments of health and basic needs in such areas, even when communities sustain little structural loss and few injuries. Responders should prepare to support such areas that might experience health-related effects exacerbated by protracted recovery periods.

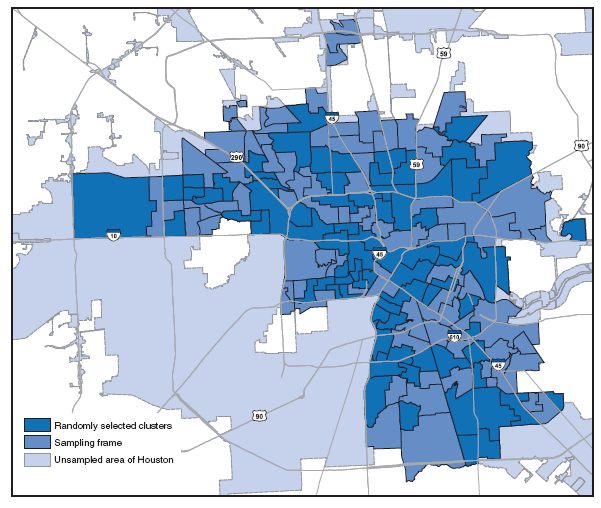

To conduct the assessment, the health department used a cluster sampling technique modified from that developed by the World Health Organization for its Expanded Programme on Immunizations (3). Because official damage assessment data to guide health assessment efforts were unavailable, initial observational reports of damage recorded by various city department employees and the local media were used to define a broad study area of 262 square miles, bound by the City of Houston Solid Waste Management department's official debris collection zones.* The study area included a sampling frame of 340,370 households and excluded sections of Houston that extended into well-publicized evacuation zones (4), from which residents had been ordered to evacuate on September 11, 2008. The study area also excluded large sections of the city for which no reports of damage were available up to the date of the assessment (Figure).

Geographic information system (GIS) software was used to divide the selected debris collection zones into 159 clusters (aggregations of census block groups) of roughly 2,000 households each, from which a simple random sample of 75 clusters was selected for assessment. Approximately 100 health department staff members and volunteers, organized into 20 teams, were trained and deployed to the field with maps of the assigned clusters. From random starting points, teams systematically sampled seven households per cluster, following the random walk method, with a specially-devised protocol for decision making at corners and intersections using a coin toss. Teams interviewed one convenient adult representative at each selected household for household-level needs and health information.

A 26-item assessment tool, adapted from that used in Houston following Tropical Storm Allison (5), was developed and designed for scanning using optical mark recognition software. Data collection was completed in 68 of 75 clusters, and responses were weighted for probability of household selection within clusters to adjust for variations in sampling during the 2-day field period. Weighted proportions and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using statistical software.

Mapping, training, conducting the field work, analysis, and report writing were completed in 8 days, and a total of 440 household-level interviews were conducted. All interviews were conducted on September 18 and 19, the 5th and 6th days after the hurricane made landfall. Among the households, 18.9%† reported having experienced flooding in their residences, (Table 1).§ Although none of the households included in the survey was in an official hurricane evacuation zone, 24.7% of households reported having evacuated the home for at least 1 day because of the storm. Only 3.9% of households indicated a current need for assistance in obtaining emergency shelter.¶ However, 23.2% of households reported that they were sheltering members of other households in their residence,** and 13.8% of households reported that some of their own family members had not returned to the residence 5--6 days after the storm had passed.†† More than half (52.3%) of all households had at least one resident belonging to one of three groups that had been previously designated by the health department as vulnerable groups of concern: children aged <2 years, pregnant women, and adults aged >60 years. Households with older adults represented the largest portion (36.1%) of households with vulnerable members.

At the time of the survey, utility services remained disrupted (Table 1). Among all households surveyed, approximately 55% reported that they had lost electricity and were still without power; 9.5% reported using gasoline-powered generators to restore limited electrical power to their homes and 29.1% reported using charcoal grills and camp stoves for cooking. Among surveyed households, 6.4% reported having no functioning toilet, and 18.3% reported no garbage pickup. More than one in four households (26.8%) reported that they needed assistance in obtaining food.§§ Other reported needs included clothing (13.1%), prescription medication (11.1%), access to medical care (11.1%), and transportation (11.1%).

Since the start of the storm, the most commonly reported new health complaints were sleep disturbances (25.2%), headache (17.1%), diarrhea (15.6%), and respiratory complaints (13.2%) (Table 2).¶¶ Household reports of new injuries since the start of the storm were relatively rare and included puncture wounds (1.9%), cuts needing stitches (1.3%), and animal bites (1.1%).

Survey results provided guidance for local hurricane disaster mitigation activities. The health department used the information to anticipate immediate needs of households affected by the storm, arrange for various referral services, and establish six comfort stations at sites across the city, from which ready-to-eat-meals, bottled water, ice, and boxed food supplies were distributed. The health department also used the results to estimate demand for emergency shelters in the aftermath of the storm and then provided support to two temporary shelters in Houston.

Reported by: M Perry, MPH, D Banerjee, PhD, M Slentz, R Stephen, MS, L Liu, MD, D Tran, MD, S Mukkavilli, MPH, RR Arafat, MD, City of Houston Dept of Health and Human Svcs, Houston, Texas.

Editorial Note:

The rapid community assessment described in this report provided information to the City of Houston Office of Emergency Management and other city officials regarding basic needs of residents across large sections of the city in the aftermath of Hurricane Ike. The health department and its many partners among community-based, faith-based, mental health, and health-care organizations used the assessment information to locate and provide health service referrals, outreach, and recovery assistance to affected households.

The findings from the assessment suggest that by the 5th and 6th day after the storm, the days when the interviews were conducted, the primary effects of Hurricane Ike upon the health of residents in the study area were related to disruption of utilities and regular access to food, medication, and health-care services. These findings are consistent with those of needs assessments conducted in other areas surrounding Galveston after Hurricane Ike (6), and after weather-related disasters such as Tropical Storm Allison and Hurricane Katrina (5,7).

Residents primarily relied on televised reports (70.4%) and radio reports (15.0%) to prepare for the storm.*** Some residents relied on neighbors, friends, or family (2.9%) as their primary source of information, or other sources (3.5%), which included communications at their workplace. Very few relied on print media as their primary information resource to prepare themselves (0.2%). The relatively high percentage of households reporting a need for assistance in obtaining food (26.8%) so soon after the hurricane suggests that many Houston residents had not prepared themselves to be without essential supplies for more than a few days, and that recommendations commonly promoted in the news media to prepare for a 3--5 day recovery period might have been inadequate or not heeded by residents. Prehurricane preparedness messages advising residents to store up to a 7-day supply of nonperishable foods and medicines were promoted by the health department through community- and faith-based organizations, by way of presentations, pamphlets, and evacuation registration guidance targeted largely at households with vulnerable population groups. Such messages might not have reached a large proportion of Houston residents, or many households might have lacked resources to amass and maintain the recommended food stores. The Hurricane Ike experience suggests that longer recovery periods should be incorporated into public health messages, using a variety of media to reach the broadest population possible. The demand for food, ice, medication, medical supplies and care indicated to emergency planners that the potential public health effects associated with protracted power outages in the area warranted new and special consideration for future disaster preparedness planning and management (6).

The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, given the urgency of collecting rapid assessment data from a large geographic area, some safeguards against selection bias were ignored, such as the requirement to revisit targeted households at which no one was present at the time of the field visit. However, other research has found that this bias might have limited impact upon estimates (8). Second, exclusion of large areas of the city from assessment prevented the results from being generalizable to the city of Houston as a whole. Third, variability in the number and constancy of trained team membership over the course of the survey might have reduced the reliability of results. Many field staff were unavailable for the entire survey period, and their replacements, when available, required repeated, and increasingly brief "just-in-time" training. The variability in trained staffing contributed to the collection of a number of incomplete or unusable returned questionnaires. Finally, the survey questions did not uniformly distinguish preexisting needs from those specifically arising from effects of the storm, particularly in terms of needs for assistance with access to medical and health-care services, clothing, and food. This made it difficult to quantify and interpret the magnitude of these and other effects of the storm, and especially their effects among households with vulnerable populations.

Efficient coordination of information between agencies responsible for postdisaster response is necessary to facilitate rapid assessment. The destructive effects of Hurricane Ike in Houston were widespread, such that preliminary damage assessment data useful for a geographically targeted assessment were not available until several months after the storm. When planning for future emergency weather events of this magnitude, local health departments should anticipate that official damage reports might not be available immediately and should therefore conduct their assessment broadly, efficiently, and as soon as possible.

Acknowledgments

The findings in this report are based, in part, on the contributions of volunteer field staff and supervisors of the Houston Department of Health and Human Services, and students from the University of Texas School of Public Health, Houston, Texas.

References

- Federal Emergency Management Authority. Hurricane Ike impact report. 2008. Available at http://www.fema.gov/pdf/hazard/hurricane/2008/ike/impact_report.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2009.

- Sanchez, LA. 2008 Hurricane Ike related cases; September 25, 2008. Houston, TX: Harris County Medical Examiner's Office; 2008. Available at http://www.hctx.net/cmpdocuments/21/hurricanes/ike02.pdf.

- Malilay J, Flanders WD, Brogan D. A modified cluster-sampling method for post-disaster rapid assessment of needs. Bull World Health Organ 1996;74:399--405.

- City of Houston Office of Emergency Management. Houston area evacuation map. Available at http://www.houstonoem.net/go/doc/1855/247859/. Accessed June 16, 2009.

- Waring SC, Reynolds KM, D'Souza GA, Arafat RR. Tropical Storm Allison rapid needs assessment---Houston, Texas, June 2001. MMWR 2002;51:365--9.

- US Department of Homeland Security. Hurricane Ike impact report: special needs populations impact assessment source document. October 2008. Available at www.disabilitypreparedness.gov/pdf/ike_snp.pdf.

- CDC. Rapid community needs assessment after Hurricane Katrina---Hancock County, Mississippi, September 14--15, 2005. MMWR 2006;55:234--6.

- Milligan P, Njie A, Bennett S. Comparison of two cluster sampling methods for health surveys in developing countries. Intl J Epidemiol 2004;33:469--76.

* The debris collection zones are a part of the Houston's overall Emergency Management Plan (Annex W), and are based on the number of homes and the estimated amount of debris that would be collected following a category 4 hurricane.

† All percentages have been weighted.

§ The term "flooded" was not specifically defined by the survey, and all evidence of it was self-reported. Residents were asked the yes-no question, "Was your home flooded?" If the response was yes, a follow-up question, "How long was it flooded?" was asked, with an open-ended response.

¶ In response to the yes-no question, "Please report whether anyone in your household needs assistance with obtaining emergency shelter."

** In response to the yes-no question, "Are you sheltering people from other households at your residence because of the storm?"

†† In response to the yes-no question, "Are household members residing someplace other than this house, today?" This was a follow-up question posed to those households that reported that they had evacuated their homes for at least one day specifically because of the storm.

§§ In response to the yes-no question, "Please report whether anyone in your household needs assistance with obtaining food."

¶¶ The question asked was "How many people staying in this house had the condition since the start of the storm?" and listed a set of conditions (A. stomachache/nausea/vomiting/diarrhea? B. respiratory/cold? C. severe headache? D. dizziness? E. sleep disturbance? F. nightmare?). Injuries were similarly assessed with the question, "Has anyone living in this house been injured since the start of the storm?" with types of injuries being listed (A. cuts needing stitches? B. puncture wounds? C. crush injury? D. animal bites? E. broken bone? F. blunt head injury? G. deaths?).

*** In response to the question, "What source did you rely on most to prepare yourself for the storm?" Only one response was expected, and the choices were television, radio, Internet, neighbor/friend/family, newspaper, and other.