Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Outbreak of Rickettsia typhi Infection --- Austin, Texas, 2008

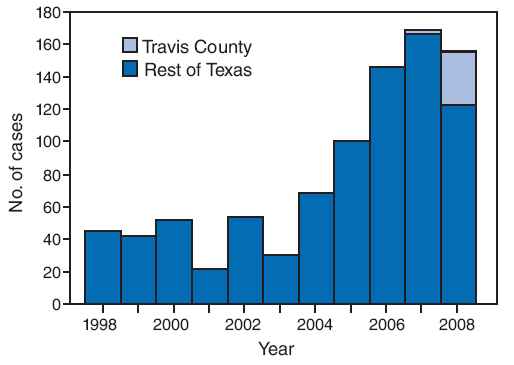

Murine typhus is a fleaborne rickettsial disease caused by the organism Rickettsia typhi. Symptoms include fever, headache, chills, vomiting, nausea, myalgia, and rash. Although murine typhus is endemic in southern Texas, only two cases had been reported during the past 10 years from Austin, located in central Texas (Figure 1). On August 8, 2008, the Austin/Travis County Department of Health and Human Services (ATCDHHS) contacted the Texas Department of State Health Services (TDSHS) concerning a cluster of 14 illnesses with serologic findings indicative of murine typhus. On August 12, 2008, TDSHS initiated an investigation with assistance from CDC to characterize the magnitude of the outbreak and assess potential animal reservoirs and peridomestic factors that might have contributed to disease. This report summarizes the clinical and environmental findings of that investigation. Thirty-three confirmed cases involved illness comparable to that associated with previous outbreaks of murine typhus. Illness ranged from mild to severe, with 73% of patients requiring hospitalization. Delayed diagnosis and administration of no or inappropriate antibiotics might have contributed to illness severity. Environmental investigation suggested that opossums and domestic animals likely played a role in the maintenance and spread of R. typhi; however, their precise role in the outbreak has not been determined. These findings underscore the need to increase awareness of murine typhus and communicate appropriate treatment and prevention measures through the distribution of typhus alerts before and throughout the peak vector season of March--November.

Murine typhus is a reportable condition in Texas, and health-care providers are required to report any suspected cases to the local health department through the National Electronic Disease Surveillance System within 1 week of detection. The first two case reports associated with this outbreak were received in April 2008. Fourteen more reports were received in May and June. Receipt of eight additional case reports in July prompted ATCDHHS to seek assistance from TDSHS. On August 8, CDC was requested to assist in the investigation. An additional 29 cases were reported during the course of the investigation, which concluded on December 1.

A suspected case was defined as illness with fever (≥100.4°F [≥38°C]) and one or more of the following: headache, rash, or myalgia. A confirmed case included 1) a fourfold or greater rise in antibody titer to R. typhi antigens between paired serum specimens taken ≥3 weeks apart, or 2) detection of R. typhi DNA in a clinical specimen by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The clinical and laboratory investigation included reviewing outpatient medical records, hospital charts, and laboratory results, in addition to interviewing all patients with suspected cases. All medical record reviews and interviews were conducted by CDC and ATCDHHS.

Clinical and Laboratory Investigation

Of the 53 cases reported during 2008, 33 (62%) were laboratory confirmed. R. typhi infection was confirmed by PCR and sequence analysis of DNA for one patient. Illness onset dates for confirmed cases ranged from March to November, with the highest number of cases occurring in June (n = 7; 21%). Most confirmed cases occurred during May--August (70%). The median age of patients was 37 years (range: 7--64 years). More males (55%) than females (45%) had confirmed illness. Patients were predominantly white (97%); 3% were black. Because data on ethnicity were not consistently available in the patient charts, ethnicity was not included in the analyses. The most commonly reported symptoms in confirmed cases were fever (100%), malaise (76%), headache (73%), chills (61%), myalgia (61%), anorexia (58%), nausea (52%), rash (46%), vomiting (42%), and diarrhea (36%).

No deaths were attributed to murine typhus; however, 73% of the confirmed patients were hospitalized, and 27% were admitted to intensive-care units. Only 51% (n = 17) of confirmed patients were prescribed antibiotics. Fifteen (88%) patients who received antibiotics received the recommended treatment with doxycycline; two received an antibiotic other than doxycycline. The median time from symptom onset to prescription of antibiotics was 8 days (range: 1--19 days).

Blood chemistry results revealed that 70% of confirmed patients experienced impaired liver function, as indicated by elevated aspartate aminotransferase, alanine transaminase, alkaline phosphate, bilirubin, and/or lactate dehydrogenase levels. Elevated creatinine and/or decreased albumin or serum protein levels indicated impaired kidney function in 21% of patients. Among the 33 patients 24% had low platelet counts, and 24% had anemia. Leukocytosis and leukopenia were each observed in 6% of patients.

Among the 12 confirmed patients whose discharge/outpatient follow-up laboratory results were available during the clinical investigation (August 12--December 1), most laboratory values were normal for leukocytes (80%), bilirubin (77%), and creatinine (92%). However, low albumin and serum protein levels persisted in 58% of cases, and impaired liver function persisted in most cases; aspartate aminotransferase levels remained elevated in 83% of cases, and alanine transaminase levels remained elevated in 92%. No additional follow-up by TDSHS or CDC is anticipated.

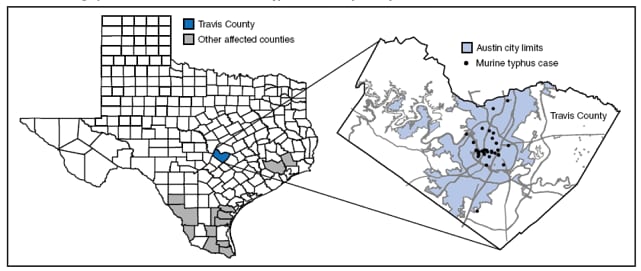

Confirmed patients were clustered in central Austin (Figure 2). Two patients resided north of Austin but worked or engaged in recreational activities in central Austin. Among the 33 confirmed cases, only two patients (6%) noted flea bites or flea exposure during the 2 weeks before illness onset. Recent close exposure to opossums or rats was reported by 18% and 15% of patients, respectively.

Environmental Investigation

During August 12--19, CDC conducted an environmental investigation with assistance from ATCDHHS. Environmental site assessments were conducted at the homes of 20 patients with confirmed cases. Blood and arthropod specimens were collected from 26 domestic pets (cats and dogs), and postmortem blood and tissue specimens were collected from 31 wild animals trapped at patients' home sites. Separate blood samples were obtained from each animal for serologic and PCR testing. On average, five fleas were collected from each opossum, and one or two from each raccoon, cat, and dog. All animal and arthropod specimens were tested for evidence of R. typhi and Rickettsia felis DNA by PCR and for seroreactive antibodies to R. typhi antigen using immunofluorescence assay.

Most patients with confirmed cases (n = 27; 82%) resided in homes with yards bordered by thick vegetation; 79% owned a dog or cat, but only 42% (n = 14) reported regularly administering flea or tick preventatives. Nineteen (95%) of the 20 households assessed had obvious evidence of wildlife or wildlife attractants on the property (e.g., pet food or water dishes outside the home or unsealed outdoor garbage containers). Among the 57 animals assessed, only 33% (n = 19) had evidence of active murine typhus infection by serology, as determined using a 1:32 titer threshold. Antibodies (immunoglobulin G [IgG]) to R. typhi were detected in three feral cats, four domestic dogs, and 12 opossums; none of four wild rats or nine raccoons tested positive (Table). None of the animal tissue (n = 57) or flea specimens (n = 139) tested positive for R. typhi or R. felis DNA by PCR. Seropositive animals were from five different postal code areas. Most seropositive animals (68%) were found in the two contiguous postal code areas where the most human cases (36%) were reported.

In response to this outbreak, ATCDHHS increased public awareness of fleaborne rickettsiosis via alerts posted on its Internet website. The alerts included a definition of murine typhus and its symptoms in addition to descriptions of how the disease is transmitted, treated, and prevented. Recommended prevention and control measures included using dog and cat flea preventatives, exterminating household rodents, eliminating rodent habitats in or near homes, using pesticides to limit flea infestations, avoiding wild animals (including feral cats and opossums), and using insect repellents containing DEET.

Reported by: J Campbell, Austin/Travis County Dept of Health and Human Svcs, Texas. ME Eremeeva, PhD, WL Nicholson, PhD, J McQuiston, DVM, National Center for Zoonotic, Vector-Borne, and Enteric Diseases; S Parks, PhD, J Adjemian, PhD, K McElroy, DVM, EIS officers, CDC.

Editorial Note:

Contemporary reports of murine typhus in the United States are sporadic and usually limited to southern Texas, southern California, and Hawaii, where enzootic foci remain and where the disease is reportable. This cluster of R. typhi cases in Austin during 2008 might represent the emergence of murine typhus in a new area. Alternatively, R. typhi might have been present in this area in reservoir species but at levels below a threshold for transmission and detection. In addition, recent changes in local ecology or transmission dynamics might have caused the emergence of clinical human cases. The low prevalence of active murine typhus infection among the animals assessed versus that in previous studies (33% versus 63%--94%) (1) precludes making conclusions about the reservoir species associated with this outbreak.

Rats are the primary animal reservoir of R. typhi (1); however, other mammals (including opossums and domestic dogs and cats) can maintain the disease, as was observed in this outbreak. Few rats were sampled and evidence of active infection was not found; however, the 67% prevalence of seropositivity among opossums points to their possible role in propagation. Domestic animals also were found to be seropositive; however, further studies would be needed to ascertain whether they played a role in propagation of the outbreak. Although fleas on opossums and cats can be infected with R. typhi, they are more often infected with the related organism Rickettsia felis (2). However, only one case of R. felis has been reported in the United States since 1994 (4). Futhermore, PCR and serologic evidence, in addition to the moderate to severe clinical course for most cases, suggest that R. typhi was the cause of this outbreak. Thus, this outbreak provides documentation of an atypical reservoir and vector in a suburban murine typhus cycle.

Based on patient symptoms and laboratory findings, the severity of illness associated with this outbreak appears comparable to previous murine typhus outbreaks in other areas (5--8). Illness severity ranged from mild to severe, with complications that required hospitalization. The patients described in this report experienced substantial delays in diagnosis, antibiotic initiation (on average 8 days after symptom onset), or lack of antibiotic therapy, which likely contributed to the high rate of hospitalizations and might have contributed to illness severity. Delays in murine typhus treatment can increase duration of symptoms and risk for complications (e.g., seizures, respiratory failure, and persistent frontal and temporal lobe dysfunction) or death (5,6). Elevated liver enzymes and decreased platelet counts in a patient with rash illness should be evaluated for rickettsiosis (5--7). All suspected murine typhus patients should be treated with doxycycline, with a minimum recommended course of 7--10 days or ≥3 days after resolution of fever (9). Health-care providers in emerging or established areas where murine typhus occurs should initiate treatment for suspected murine typhus cases on clinical and epidemiologic considerations without waiting for laboratory confirmation of the diagnosis (9).

Murine typhus might now be established in the Austin and Travis County area and should be considered an ongoing public health threat. As of September 14, 2009, a total of 24 new suspected cases had been reported to ATCDHHS. Illness onsets ranged from April 29 to July 29. The median age of patients (37 years; range: 3--67 years) and symptom profile has been similar to 2008 cases. The rate of hospitalization (54%) has been lower, which might be attributable to increased knowledge of the presentation and appropriate treatment of the disease as a result of notices from Texas Medical Society and ATCDHHS public health education web-based campaigns. Health-care providers should be aware of the potential for travel-associated exposures among visitors to Austin or other endemic areas and notify their local or state health officials of suspected cases of murine typhus.

References

- Azad AF. Epidemiology of murine typhus. Annu Rev Entomol 1990;35:553--69.

- Karpathy SE, Hayes EK, Williams AM, et al. Detection of Rickettsia felis and Rickettsia typhi in areas of California endemic for murine typhus. Clin Microbiol Infect. In press 2009.

- Wiggers RJ, Martin MC, Bouyer D. Rickettsia felis infection rates in an east Texas population. Tex Med 2005;101:56--8.

- Schrieffer ME, Sacci JB Jr, Dumler JS, Bullen MG, Azad AF. Identification of a novel rickettsial infection in a patient diagnosed with murine typhus. J Clin Microbiol 1994;32:949--54.

- Dumler JS, Taylor JP, Walker DH. Clinical and laboratory features of murine typhus in south Texas, 1980 through 1987. JAMA 1991;266:1365--70.

- CDC. Murine typhus---Hawaii, 2002. MMWR 2003;52:1224--6.

- Whiteford SF, Taylor JP, Dumler SJ. Clinical, laboratory, and epidemiologic features of murine typhus in 97 Texas children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;155:396--400.

- Fergie JE, Purcell K, Wanat P, Wanat D. Murine typhus in South Texas children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000;19:535--8.

- Dumler JS, Walker DH. Rickettsia typhi (murine typhus). In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and practices of infectious diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005:2306--9.

|

What is already known on this topic? Although murine typhus, a fleaborne disease often transmitted to humans through contact with rats, is endemic in southern Texas, only two cases had been reported in central Texas during the past 10 years. What is added by this report? Illness associated with this central Texas outbreak of 33 confirmed cases (73% in patients who were subsequently hospitalized) was comparable to previous outbreaks of murine typhus; however, the suspected vector (cat flea) and reservoir (opossum) were atypical for a suburban setting. What are the implications for public health practice? Health-care providers and the public should be aware of the symptoms, appropriate treatment and prevention measures, and the importance of promptly notifying local or state health officials of suspected cases of murine typhus. |

FIGURE 1. Number of confirmed murine typhus cases,* by year --- Travis County and rest of Texas, 1998--2008

* Defined as illness with fever (≥100.4°F[≥38°C]) and one or more of the following: headache, rash, or myalgias, plus laboratory confirmation via 1) a fourfold or greater rise in antibody titer to Rickettsia typhi antigens between paired serum specimens taken ≥3 weeks apart, or 2) detection of R. typhi DNA in a clinical specimen by polymerase chain reaction.

Alternate Text: The figure shows the number of confirmed murine typhus cases by year In Travis County and the rest of Texas from 1998 through 2008. Although murine typhus is endemic in southern Texas, only two cases had been reported during the past 10 years from Austin, located in Travis County in central Texas.

* Defined as illness with fever (≥100.4°F[≥38°C]) and one or more of the following: headache, rash, or myalgias, plus laboratory confirmation via 1) a fourfold or greater rise in antibody titer to Rickettsia typhi antigens between paired serum specimens taken ≥3 weeks apart, or 2) detection of R. typhi DNA in a clinical specimen by polymerase chain reaction.

Alternate Text: The figure shows the geographic location of confirmed murine typhus cases in Texas in 2008 by county. Confirmed patients were clustered in central Austin. Two patients resided north of Austin but worked or engaged in recreational activities in central Austin.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services. |

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Date last reviewed: 11/19/2009