Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Outbreak of Erythema Nodosum of Unknown Cause --- New Mexico, November 2007--January 2008

Erythema nodosum (EN) is a form of panniculitis, which has been associated with several infectious and noninfectious etiologies (1,2). EN clusters have been associated with outbreaks of Coccidioides immitis (3), Histoplasma capsulatum (4), and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infections (5). In December 2007, a physician in a rural New Mexico community of approximately 10,000 persons reported to the New Mexico Department of Health (NMDOH) that 13 patients had been diagnosed with EN since mid-November. No EN outbreak had ever been detected in this community, and since 2006, only one diagnosis of EN had been made at the local health-care facility. NMDOH initiated an investigation to confirm the existence of the outbreak, determine the underlying etiology, and implement control measures. This report describes the results of that investigation. Twenty-five EN cases were identified. Seventeen of 20 patients who answered a standard questionnaire reported being at a construction site with crowded and dusty conditions before EN onset. Nine of 15 chest radiographs were abnormal. Serologic test results were interpreted as negative for mycotic agents and inconclusive for Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. No etiology of the outbreak could be found. During an EN outbreak, timely (acute and convalescent) specimen collection (ideally from case-patients and control subjects to determine baseline seropositivity) and sensitive tests (e.g., polymerase chain reaction [PCR]) are essential to differentiate among possible causes of EN.

The rural community where the EN outbreak was identified is served by a single inpatient and outpatient health-care facility. Patients from this community do not have local access to dermatology or infectious disease specialty care. During mid-November to mid-December 2007, the town had been preparing for a festival, including construction of buildings where festivities would be held. Activities at the construction sites included building, digging, cooking (both inside and outside), and handling sheep. Among the initial 13 patients diagnosed with EN, nine complained of nodules on the extremities and five of cough.* Because of the clinical presentations, reported exposure to dirt, and published literature on EN outbreaks, the physicians and investigators hypothesized initially that this EN outbreak was caused by a mycotic agent (e.g., C. immitis or H. capsulatum), although these agents were not known to be endemic in this region (C. immitis is found to the south and west, and H. capsulatum to the east of the region where this EN outbreak occurred).

NMDOH initiated an investigation on December 20, 2007. A case was defined as physician-diagnosed EN in a person examined at the health care-facility during September 1, 2007--March 7, 2008. International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes were used to identify patients with EN in the facility's electronic database. Medical record reviews were conducted by physician-investigators to confirm each diagnosis. Additionally, investigators visited all patients who had illness meeting the case definition to complete a standardized in-person questionnaire about signs, symptoms, and previous activities, including time spent outdoors, occupation, dust exposure, travel, animal contacts, attendance at public events, residential proximity to any construction, and participation in construction activities. Beginning on December 20, 2007, all patients with newly diagnosed EN were recommended to undergo acute sera testing, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) testing, chest radiograph, tuberculin skin test (TST), and testing for group A streptococcus (GAS) infection (via antistreptolysin O titer [ASO] and throat swab for GAS rapid antigen detection test [RADT]). ASO titers were performed by a reference laboratory; titers >200 for adults and >150 for children were considered positive. No convalescent ASO titers were performed.

CDC tested all sera for the thermally dimorphic fungi C. immitis, H. capsulatum, Blastomycosis dermatitidis, and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis by using complement fixation and immunodiffusion. Cryptococcus neoformans antigen and Sporothrix schenckii antibody tests were performed using the latex agglutination method. Detection of antibody to C. neoformans was performed using the tube agglutination method. Convalescent sera were drawn 4--12 weeks after symptom onset to allow a significant (fourfold or greater) rise in antibodies against fungal antigens (if any), given the relatively long time needed for seroconversion (M. Lindsley, CDC, personal communication, 2008). CDC also tested sera for M. pneumoniae by using the nonquantitative immunoglobulin M (IgM)-specific Mycoplasma ImmunoCard (Meridian Bioscience, Cincinnati, Ohio). This test only provides qualitative results, so assessing changes in titer was not possible. The analysis included patients who provided at least one serum sample or completed the questionnaire.

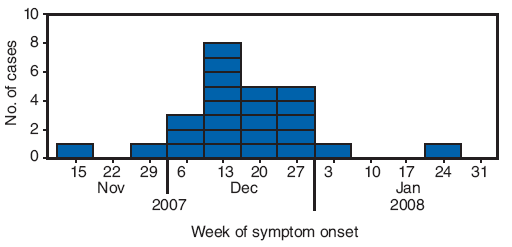

A total of 25 patients met the case definition. All patients were from the community served by the health-care clinic, and some were from the same family or extended family. Illness onsets occurred during November 15, 2007--January 22, 2008 (Figure 1). The median age of patients was 42 years (range: 4−68 years), and 17 patients (68%) were female. Twenty-four patients (96%) had nodules on the lower extremities and 13 (52%) on the upper extremities. Ten of 19 patients had a temperature ≥100.4°F (≥38°C) (range: 98.4−102.7°F [36.9--39.3°C]), and 11 of 22 patients reported cough. Five patients had cough and a temperature ≥100.4°F (≥38°C) (Table), one patient had a diagnosis of pharyngitis. None of the 25 patients were hospitalized.

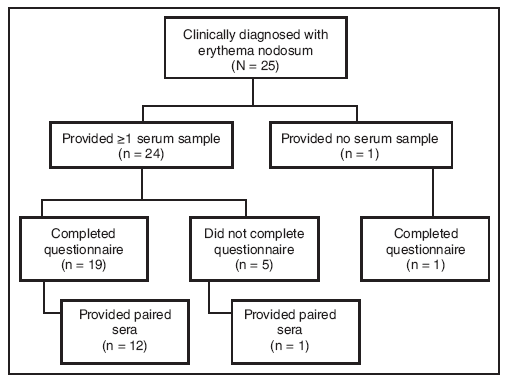

Twenty patients completed the questionnaire (Figure 2). After nodules, the most commonly self-reported symptoms were joint pain and fatigue (80%), muscle pain (70%), fever (65%), and cough (60%) (Table). Five patients (20%) reported one or more comorbid conditions, including lung disease and latent tuberculosis (one patient), kidney disease (one), and diabetes (four). Seventeen of 20 (85%) patients participated in the construction of one building to be used during the festival.

A total of 15 patients had a chest radiograph. Nine radiographs were abnormal; three showed unilateral findings and six bilateral findings (Table). Five of the nine radiographs were interpreted as suggestive for pneumonia. All four ESR tests performed were elevated, and all 12 TST results were negative. Of 20 patients tested for GAS, 12 were tested by RADT and acute ASO titers, two by RADT only, and six by acute ASO titers only. Two patients of 14 had a positive RADT, and six of 18 patients had positive acute ASO titers (Table). The patient diagnosed with pharyngitis had positive GAS results.

Twenty-four patients provided at least one serum sample; of these, 13 provided paired sera (Figure 1). Twelve paired sera were tested for antibodies to possible fungal pathogens (Table). Although certain sera displayed elevated titers to the thermally dimorphic fungi, no significant (fourfold or greater) increase in antibody titer was observed when comparing complement fixation titers for C. immitis, H. capsulatum, P. brasiliensis, and B. dermatitidis (Table). Subsequent testing of acute sera for cryptococcal antigen and paired sera from 12 patients for C. neoformans and S. schenckii antibody was uniformly negative. Fifty percent (11 of 22) of patients tested for IgM against M. pneumoniae had at least one positive sample (Table). No patients received a diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection, but eight patients had clinical or radiologic signs compatible with M. pneumoniae infection (temperature ≥100.4ºF [≥38.0ºC] and cough, or clinical or radiologic diagnosis of pneumonia) (7). Of these eight patients, only four had a positive M. pneumoniae serology.

The absence of disease severity did not justify collection of more invasive specimens (e.g., via bronchoalveolar lavage or lung biopsy). No nodule biopsies were performed. Most patients received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to treat symptoms and pain associated with EN. Six patients with respiratory signs, including three with diagnosis of pneumonia and four with positive RADT results received antibiotics.

Patients with EN were encouraged to be evaluated further at the local health-care facility to rule out any serious underlying conditions. In the absence of an identified etiology, specific recommendations for control measures could not be provided. Nonetheless, close follow-up for patients with pulmonary signs and abnormal chest radiographs was recommended. EN signs and symptoms resolved in all patients. No long-term complications among patients with EN have been reported. Construction activities were suspended at the site during the investigative period.

Reported by: CM Sewell, DrPH, MG Landen, MD, JP Baumbach, MD, ES Hatton, New Mexico Dept of Health; BA Redd, MD, X-Ray Associates of New Mexico, Albuquerque. JT Redd, MD, JE Cheek MD, B Reilley, MPH, Div of Epidemiology and Disease Prevention, Indian Health Svc. BJ Park, MD, M Lindsley, PhD, Div of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center For Zoonotic, Vector-Borne, and Enteric Diseases; JM Winchell, PhD, Div of Viral Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases; T Naimi, MD, Div of Adult and Community Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; C Dubray, MD, AM Wendelboe, PhD, EIS officers, CDC.

Editorial Note:

This investigation confirmed an EN outbreak in a rural community in New Mexico during the winter of 2007−2008. Despite extensive assessment for known etiologies and associated illnesses, no etiology for the outbreak could be found. Serology for mycotic pathogens did not support the initial hypothesis that the outbreak was caused by a mycotic agent. Most patients were exposed to dust, similar to previous outbreaks involving C. immitis (3) and H. capsulatum (8). However, these agents are not known to be endemic in the region where this outbreak occurred, and all C. immitis and H. capsulatum serologic results were negative. Other reported causes of EN were considered systematically, including those not previously known to be associated with clusters and those not associated with dust exposure (1). Investigators hypothesized that M. pneumoniae might be the etiologic agent because of respiratory signs and symptoms among patients and similarity to previous descriptions of community outbreaks of M. pneumoniae infection (9). Eleven (50%) cases had positive serology for M. pneumoniae. However, the general population can have a high positive serologic baseline for M. pneumoniae (10), and commercially available serologic tests have poor specificity (7). Also, diagnoses of M. pneumoniae infection in the community did not increase during the outbreak period, and of eight patients with a clinical presentation compatible with M. pneumoniae infection, only four had a positive serology. For these reasons, investigators concluded that M. pneumoniae likely was not the cause of this outbreak.

The estimated national EN incidence is one to five cases per 100,000 population annually (6). When associated with GAS infection, upper respiratory symptoms can precede EN by approximately 2--3 weeks. When associated with C. immitis infection, EN is preceded by upper respiratory symptoms, and its onset tends to occur before IgM antibody serology becomes positive (6). In this investigation, the negative TST results almost certainly ruled out M. tuberculosis infection. Likewise, GAS likely was not the etiologic agent. Only one patient with EN was diagnosed with acute pharyngitis, and the majority of tests for GAS were negative. Other known causes of EN outbreaks, such as Y. pseudotuberculosis infection, were unlikely (5).

This is the first reported EN cluster with unknown cause. Carrots contaminated with Y. pseudotuberculosis were the cause of a point-source outbreak of gastrointestinal illness and EN among school children (5). In a large outbreak of H. capsulatum in Indianapolis, 4.1% of patients initially had EN, with the majority of them having respiratory signs (4).

These findings are subject to at least three limitations. First, the size of the outbreak likely was larger than reported because only patients receiving EN diagnosis at the clinic were included. Second, PCR assays for M. pneumonia, which are particularly sensitive during the 21 days after symptom onset (9), were not used in combination with serologic test because M. pneumoniae infection was not considered in the differential diagnosis when patients were acutely ill. Finally, an analytic investigation (e.g., case-control study), which might have helped identify the etiology of the cluster and determine baseline seropositivity levels in controls, could not be conducted.

This report highlights the difficulties of defining an EN outbreak etiology when multiple possible infectious causes are possible. If a similar EN outbreak occurred in a community, appropriate (nasopharyngeal and/or oropharyngeal) and timely specimen collection for PCR assays and serologic tests (acute and convalescent) should be used to confirm the cause of the outbreak.

Acknowledgments

This report is based, in part, on contributions by the public health nurses, laboratory personnel, and other health-care workers involved in this investigation.

References

- Requena L, Sanchez Yus E. Erythema nodosum. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2007;26:114--25.

- Cribier B, Caille A, Heid E, Grosshans E. Erythema nodosum and associated diseases: a study of 129 cases. Int J Dermatol 1998;37:667--72.

- Cairns L, Blythe D, Kao A, et al. Outbreak of coccidioidomycosis in Washington state residents returning from Mexico. Clin Infect Dis 2000;30:61−4.

- Ozols II, Wheat LJ. Erythema nodosum in an epidemic of histoplasmosis in Indianapolis. Arch Dermatol 1981;117:709--12.

- Jalava K, Hakkinen M, Valkonen M, et al. An outbreak of gastrointestinal illness and erythema nodosum from grated carrots contaminated with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. J Infect Dis 2006;194:1209--16.

- Schwartz RA, Nervi SJ. Erythema nodosum: a sign of systemic disease. Am Fam Physician 2007;75:695--700.

- Thurman KA, Walter ND, Schwartz SB, et al. Comparison of laboratory diagnostic procedures for detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in community outbreaks. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48:1244--9.

- Huhn GD, Austin C, Carr M, et al. Two outbreaks of occupationally acquired histoplasmosis: more than workers at risk. Environ Health Perspect 2005;113:585--9.

- CDC. Outbreak of community-acquired pneumonia caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae---Colorado, 2000. MMWR 2001;50:227--30.

- Nir-Paz R, Michael-Gayego A, Ron M, Block C. Evaluation of eight commercial tests for Mycoplasma pneumoniae antibodies in the absence of acute infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006;12:685--8.

* The diagnosis of EN is clinical (i.e., the sudden eruption of erythematous tender nodules and plaques located predominantly on the lower extremities). Nodules are self-limited, typically resolving in 6 weeks. In doubtful cases, a punch biopsy may be performed to confirm the diagnosis (6).

|

What is already known on this topic? Clusters of erythema nodosum (EN), a form of panniculitis, have been associated with outbreaks of Coccidioides immitis, Histoplasma capsulatum, and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infections. What is added by this report? Investigation of an outbreak of 25 cases of EN in a rural community in New Mexico did not identify an etiology despite an extensive search for known causative agents. What are the implications for public health practice? During an EN outbreak, timely specimen collection and sensitive tests (e.g., polymerase chain reaction) are essential to differentiate among possible causes of EN. |

FIGURE 1. Number of erythema nodosum cases* (N = 25), by week of symptom onset --- New Mexico, 2007--2008

* Defined as physician-diagnosed erythema nodosum in a person examined at one New Mexico health-care facility during September 1, 2007--March 7, 2008.

Alternate Text: The figure above shows the number of erythema nodosum cases (N = 25), by week of symptom onset in New Mexico from Nov. 2007 to Jan. 2008. In December 2007, a physician in a rural New Mexico community of approximately 10,000 persons reported to the New Mexico Department of Health that 13 patients had been diagnosed with EN since mid-November. The rural community where the EN outbreak was identified is served by a single inpatient and outpatient health-care facility. Beginning on December 20, 2007, all patients newly diagnosed with EN were recommended to undergo acute sera testing, erythrocyte sedimentation rate testing, chest radiograph, tuberculin skin test, and testing for group A streptococcus (GAS) infection (via anti-streptolysin O titer and throat swab for GAS rapid antigen detection test). A total of 25 patients met the case definition. All patients were from the community served by the health-care clinic, and some were from the same family or extended family. Illness onsets occurred during November 15, 2007-January 22, 2008.

FIGURE 2. Number of patients with erythema nodosum* (N = 25) who provided sera (single or paired) and/or completed a standardized questionnaire ---- New Mexico, 2007--2008

* Defined as physician-diagnosed erythema nodosum in a person examined at one New Mexico health-care facility during September 1, 2007--March 7, 2008.

Alternate Text: The figure above shows the number of patients with erythema nodosum (N = 25) who provided sera (single or paired) and/or completed the standardized questionnaire in New Mexico during an outbreak of erythema nodosum which occurred during November 2007-January 2008. Twenty patients completed the questionnaire.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services. |

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Date last reviewed: 12/9/2009