|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

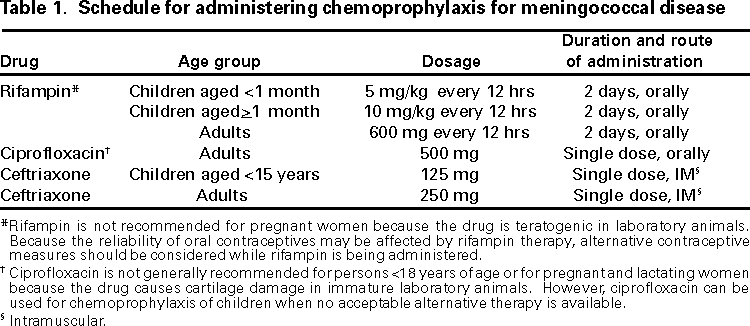

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Prevention and Control of Meningococcal DiseaseRecommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)SummaryThis report summarizes and updates an earlier published statement issued by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices concerning the control and prevention of meningococcal disease (MMWR 1997:46[No. RR-5]:1--21) and provides updated recommendations regarding the use of meningococcal vaccine. INTRODUCTIONEach year, 2,400--3,000 cases of meningococcal disease occur in the United States, resulting in a rate of 0.8--1.3 per 100,000 population (1--3). The case-fatality ratio for meningococcal disease is 10% (2), despite the continued sensitivity of meningococcus to many antibiotics, including penicillin (4). Meningococcal disease also causes substantial morbidity: 11%--9% of survivors have sequelae (e.g., neurologic disability, limb loss, and hearing loss [5,6]). During 1991--1998, the highest rate of meningococcal disease occurred among infants aged <1 year; however, the rate for persons aged 1823 years was also higher than that for the general population (1.4 per 100,000) (CDC, National Electronic Telecommunications System for Surveillance, unpublished data). BACKGOUNDIn the United States, 95%--97% of cases of meningococcal disease are sporadic; however, since 1991, the frequency of localized outbreaks has increased (7--8). Most of these outbreaks have been caused by serogroup C. However, in the past 3 years, localized outbreaks caused by serogroup Y and B organisms have also been reported (8). The proportion of sporadic meningococcal cases caused by serogroup Y also increased from 2% during 1989--991 to 30% during 1992--1996 (2,9). The proportion of cases caused by each serogroup varies by age group; more than half of cases among infants aged <1 year are caused by serogroup B, for which no vaccine is licensed or available in the United States (2,10). Persons who have certain medical conditions are at increased risk for developing meningococcal disease, particularly persons who have deficiencies in the terminal common complement pathway (C3, C5-9) (11). Antecedent viral infection, household crowding, chronic underlying illness, and both active and passive smoking also are associated with increased risk for meningococcal disease (12--19). During outbreaks, bar or nightclub patronage and alcohol use have also been associated with higher risk for disease (20--22). In the United States, blacks and persons of low socioeconomic status have been consistently at higher risk for meningococcal disease (2,3,12,18). However, race and low socioeconomic status are likely risk markers, rather than risk factors, for this disease. A recent multi-state, case-control study, in which controls were matched to case-patients by age group, revealed that in a multivariable analysis (controlling for sex and education), active and passive smoking, recent respiratory illness, corticosteroid use, new residence, new school, Medicaid insurance, and household crowding were all associated with increased risk for meningococcal disease (13). Income and race were not associated with increased risk. Additional research is needed to identify groups at risk that could benefit from prevention efforts. MENINGOCOCCAL POLYSACCHARIDE VACCINESThe quadrivalent A, C, Y, W-135 vaccine (Menomune®-A,C,Y,W-135, manufactured by Aventis Pasteur) is the formulation currently available in the United States (23). Each dose consists of 50 µg of the four purified bacterial capsular polysaccharides. Menomune® is available in single-dose and 10-dose vials. (Fifty-dose vials are no longer available.) Primary VaccinationFor both adults and children, vaccine is administered subcutaneously as a single, 0.5-ml dose. The vaccine can be administered at the same time as other vaccines but should be given at a different anatomic site. Protective levels of antibody are usually achieved within 7--10 days of vaccination. Vaccine Immunogenicity and EfficacyThe immunogenicity and clinical efficacy of the serogroups A and C meningococcal vaccines have been well established. The serogroup A polysaccharide induces antibody in some children as young as 3 months of age, although a response comparable with that occurring in adults is not achieved until age 4--5 years. The serogroup C component is poorly immunogenic in recipients aged <18--24 months (24,25). The serogroups A and C vaccines have demonstrated estimated clinical efficacies of >85% in school-aged children and adults and are useful in controlling outbreaks (26--29). Serogroups Y and W-135 polysaccharides are safe and immunogenic in adults and in children aged >2 years (30--32); although clinical protection has not been documented, vaccination with these polysaccharides induces bactericidal antibody. The antibody responses to each of the four polysaccharides in the quadrivalent vaccine are serogroup-specific and independent. Reduced clinical efficacy has not been demonstrated among persons who have received multiple doses of vaccine. However, recent serologic studies have suggested that multiple doses of serogroup C polysaccharide may cause immunologic tolerance to the group C polysaccharide (33,34). Duration of ProtectionIn infants and children aged <5 years, measurable levels of antibodies against the group A and C polysaccharides decrease substantially during the first 3 years following a single dose of vaccine; in healthy adults, antibody levels also decrease, but antibodies are still detectable up to 10 years after vaccine administration (25,35--38). Similarly, although vaccine-induced clinical protection likely persists in school-aged children and adults for at least 3 years, the efficacy of the group A vaccine in children aged <5 years may decrease markedly within this period. In one study, efficacy declined from >90% to <10% 3 years after vaccination among children who were aged <4 years when vaccinated; efficacy was 67% among children who were >4 years of age at vaccination (39).

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR USE OF MENINGOCOCCAL VACCINECurrent Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) guidelines (1) suggest that routine vaccination of civilians with the quadrivalent meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine is not recommended because of its relative ineffectiveness in children aged <2 years (the age group with the highest risk for sporadic disease) and because of its relatively short duration of protection. However, the vaccine is recommended for use in control of serogroup C meningococcal outbreaks. An outbreak is defined by the occurrence of three or more confirmed or probable cases of serogroup C meningococcal disease during a period of <3 months, with a resulting primary attack rate of at least 10 cases per 100,000 population. For calculation of this threshold, population-based rates are used and not age-specific attack rates, as have been calculated for college students. These recommendations are based on experience with serogroup C meningococcal outbreaks, but these principles may be applicable to outbreaks caused by the other vaccine-preventable meningococcal serogroups, including Y, W-135, and A. College freshmen, particularly those living in dormitories or residence halls, are at modestly increased risk for meningococcal disease compared with persons the same age who are not attending college. Therefore, ACIP has developed recommendations that address educating students and their parents about the risk for disease and about the vaccine so they can make individualized, informed decisions regarding vaccination. (See MMWR Vol. 49, RR-7, which can be referenced in the pages following this report.) Routine vaccination with the quadrivalent vaccine is also recommended for certain high-risk groups, including persons who have terminal complement component deficiencies and those who have anatomic or functional asplenia. Research, industrial, and clinical laboratory personnel who are exposed routinely to Neisseria meningitidis in solutions that may be aerosolized also should be considered for vaccination (1). Vaccination with the quadrivalent vaccine may benefit travelers to and U.S. citizens residing in countries in which N. meningitidis is hyperendemic or epidemic, particularly if contact with the local population will be prolonged. Epidemics of meningococcal disease are recurrent in that part of sub-Saharan Africa known as the "meningitis belt," which extends from Senegal in the West to Ethiopia in the East (40). Epidemics in the meningitis belt usually occur during the dry season (i.e., from December to June); thus, vaccination is recommended for travelers visiting this region during that time. Information concerning geographic areas for which vaccination is recommended can be obtained from international health clinics for travelers, state health departments, and CDC (telephone [404] 332-4559; internet http://www.cdc.gov/travel/). RevaccinationRevaccination may be indicated for persons at high risk for infection (e.g., persons residing in areas in which disease is epidemic), particularly for children who were first vaccinated when they were <4 years of age; such children should be considered for revaccination after 2--3 years if they remain at high risk. Although the need for revaccination of older children and adults has not been determined, antibody levels rapidly decline over 2--3 years, and if indications still exist for vaccination, revaccination may be considered 3--5 years after receipt of the initial dose (1). Precautions and ContraindicationsPolysaccharide meningococcal vaccines (both A/C and A/C/Y/W-135) have been extensively used in mass vaccination programs as well as in the military and among international travelers. Adverse reactions to polysaccharide meningococcal vaccines are generally mild; the most frequent reaction is pain and redness at the injection site, lasting for 1--2 days. Estimates of the incidence of such local reactions have varied, ranging from 4% to 56% (41,42). Transient fever occurred in up to 5% of vaccinees in some studies and occurs more commonly in infants (24,43). Severe reactions to polysaccharide meningococcal vaccine are uncommon (24,32,41--48) (R. Ball, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, personal communication). Most studies report the rate of systemic allergic reactions (e.g., urticaria, wheezing, and rash) as 0.0--0.1 per 100,000 vaccine doses (24,48). Anaphylaxis has been documented in <0.1 per 100,000 vaccine doses (23,47). Neurological reactions (e.g., seizures, anesthesias, and paresthesias) are also infrequently observed (42,47). The Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) is a passive surveillance system that detects adverse events that are temporally (but not necessarily causally) associated with vaccination, including adverse events that occur in military personnel. During 1991--1998, a total of 4,568,572 doses of polysaccharide meningococcal vaccine were distributed; 222 adverse events were reported for a rate of 49 adverse events per million doses. In 1999, 42 reports of adverse events were received, but the total number of vaccine doses distributed in 1999 is not yet available (R. Ball, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, personal communication). In the United States from July 1990 through October 1999, a total of 264 adverse events (and no deaths) were reported. Of these adverse events, 226 were categorized as "less serious," with fever, headache, dizziness, and injection-site reactions most commonly reported. Thirty-eight serious adverse events (i.e., those that require hospitalization, are life-threatening, or result in permanent disability) that were temporally associated with vaccination were reported. Serious injection site reactions were reported in eight patients and allergic reactions in three patients. Four cases of Guillain-Barré Syndrome were reported in adults 7--16 days after receiving multiple vaccinations simultaneously, and one case of Guillain-Barré Syndrome was reported in a 9-year-old boy 32 days after receiving meningococcal vaccine alone. An additional seven patients reported serious nervous system abnormalities (e.g., convulsions, paresthesias, diploplia, and optic neuritis); all of these patients received multiple vaccinations simultaneously, making assessment of the role of meningococcal vaccine difficult. Of the 15 miscelleneous adverse events, only three occurred after meningococcal vaccine was administered alone. The minimal number of serious adverse events coupled with the substantial amount of vaccine distributed (>4 million doses) indicate that the vaccine can be considered safe (R. Ball, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, personal communication). Studies of vaccination during pregnancy have not documented adverse effects among either pregnant women or newborns (4951). Based on data from studies involving the use of meningococcal vaccines and other polysaccharide vaccines during pregnancy, altering meningococcal vaccination recommendations during pregnancy is unnecessary. ANTIMICROBIAL CHEMOPROPHYLAXISIn the United States, the primary means for prevention of sporadic meningococcal disease is antimicrobial chemoprophylaxis of close contacts of infected persons (Table 1). Close contacts include a) household members, b) day care center contacts, and c) anyone directly exposed to the patient's oral secretions (e.g., through kissing, mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, endotracheal intubation, or endotracheal tube management). The attack rate for household contacts exposed to patients who have sporadic meningococcal disease is an estimated four cases per 1,000 persons exposed, which is 500-800 times greater than for the total population (52). Because the rate of secondary disease for close contacts is highest during the first few days after onset of disease in the index patient, antimicrobial chemoprophylaxis should be administered as soon as possible (ideally within 24 hours after identification of the index patient). Conversely, chemoprophylaxis administered >14 days after onset of illness in the index patient is probably of limited or no value. Oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal cultures are not helpful in determining the need for chemoprophylaxis and may unnecessarily delay institution of this preventive measure. Rifampin, ciprofloxacin, and ceftriaxone are all 90%--95% effective in reducing nasopharyngeal carriage of N. meningitidis and are all acceptable alternatives for chemoprophylaxis (53--56). Systemic antimicrobial therapy of meningococcal disease with agents other than ceftriaxone or other third-generation cephalosporins may not reliably eradicate nasopharyngeal carriage of N. meningitidis. If other agents have been used for treatment, the index patient should receive chemoprophylactic antibiotics for eradication of nasopharyngeal carriage before being discharged from the hospital (57). PROSPECTS FOR IMPROVED MENINGOCOCCAL VACCINESSerogroup A, C, Y, and W-135 meningococcal polysaccharides have been chemically conjugated to protein carriers. These meningococcal conjugate vaccines provoke a T-cell-dependent response that induces a stronger immune response in infants, primes immunologic memory, and leads to booster response to subsequent doses. These vaccines are expected to provide a longer duration of immunity than polysaccharides, even when administered in an infant series, and may provide herd immunity through protection from nasopharyngeal carriage. Clinical trials evaluating these vaccines are ongoing (58--60). When compared with polysaccharide vaccine, conjugated A and C meningococcal vaccines in infants and toddlers have resulted in similar side effects but improved immune response. Prior vaccination with group C polysaccharide likely does not prevent induction of memory by a subsequent dose of conjugate vaccine (61). In late 1999, conjugate C meningococcal vaccines were introduced in the United Kingdom, where rates of meningococcal disease are approximately 2 per 100,000 population, and 30%--40% of cases are caused by serogroup C (62). In phase I of this program, infants are being vaccinated at 2, 3, and 4 months concurrently with DTP, Hib, and polio vaccines. Children aged 4--13 months are receiving "catch-up" vaccinations. Children aged 15--17 years are receiving one dose of conjugate C vaccine, and entering college students are receiving one dose of bivalent A/C polysaccharide vaccine. In phase II, scheduled to start in June 2000, a dose of conjugate vaccine will be administered to children aged 14 months--14 years and to persons aged 18--20 years who are not enrolled in college (62). Conjugate meningococcal vaccines should be available in the United States within the next 2--4 years. In the interim, the polysaccharide vaccine should not be incorporated into the routine childhood immunization schedule, because the currently available meningococcal polysaccharide vaccines provide limited efficacy of short duration in young children (39), in whom the risk for disease is highest (2,3). Because the group B polysaccharide is not immunogenic in humans, immunization strategies have focused primarily on noncapsular antigens (10,63). Several of these vaccines, developed from specific strains of serogroup B meningococci, have been safe, immunogenic, and efficacious among children and adults and have been used to control outbreaks in South America and Scandinavia (64--68). Strain-specific differences in outer-membrane proteins suggest that these vaccines may not provide protection against all serogroup B meningococci (69). No serogroup B vaccine is currently licensed or available in the United States. CONCLUSIONSN. meningitidis is a leading cause of bacterial meningitis and sepsis in older children and young adults in the United States. Antimicrobial chemoprophylaxis of close contacts of persons who have sporadic meningococcal disease is the primary means for prevention of meningococcal disease in the United States. The quadrivalent polysaccharide meningococcal vaccine (which protects against serogroups A, C, Y, and W-135) is recommended for control of serogroup C meningococcal disease outbreaks and for use among persons in certain high-risk groups. Travelers to countries in which disease is hyperendemic or epidemic may benefit from vaccination. In addition, college freshmen, especially those who live in dormitories, should be educated about meningococcal disease and the vaccine so that they can make an educated decision about vaccination. Conjugate C meningococcal vaccines were recently introduced into routine childhood immunization schedules in the United Kingdom. These vaccines should be available in the United States within 2--4 years, offering a better tool for control and prevention of meningococcal disease. References

Table 1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 6/27/2000 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|