|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Prevention and Control of InfluenzaRecommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)An erratum has been published for this article. To view the erratum, please click here. Prepared by The material in this report was prepared for publication by the National Center for Infectious Diseases, James M. Hughes, M.D., Director; Division of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, James W. LeDuc, Ph.D., Acting Director; the National Immunization Program, Walter A. Orenstein, M.D., Director; and the Epidemiology and Surveillance Division, Melinda Wharton, M.D., Director. SummaryThis report updates the 2001 recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) regarding the use of influenza vaccine and antiviral agents (MMWR 2001;50[No. RR-4]:1--44). The 2002 recommendations include new or updated information regarding 1) the timing of influenza vaccination by risk group; 2) influenza vaccine for children aged 6--23 months; 3) the 2002--2003 trivalent vaccine virus strains: A/Moscow/10/99 (H3N2)-like, A/New Caledonia/20/99 (H1N1)-like, and B/Hong Kong/330/2001-like strains; and 4) availability of certain influenza vaccine doses with reduced thimerosal content. A link to this report and other information related to influenza can be accessed at the website for the Influenza Branch, Division of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, CDC, at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/flu/fluvirus.htm. IntroductionEpidemics of influenza typically occur during the winter months and are responsible for an average of approximately 20,000 deaths/year in the United States (1,2). Influenza viruses also can cause pandemics, during which rates of illness and death from influenza-related complications can increase dramatically worldwide. Influenza viruses cause disease among all age groups (3--5). Rates of infection are highest among children, but rates of serious illness and death are highest among persons aged >65 years and persons of any age who have medical conditions that place them at increased risk for complications from influenza (3,6--8). Influenza vaccination is the primary method for preventing influenza and its severe complications. In this report from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the primary target groups recommended for annual vaccination are 1) groups who are at increased risk for influenza-related complications (e.g., persons aged >65 years and persons of any age with certain chronic medical conditions); 2) persons aged 50--64 years, because this group has an elevated prevalence of certain chronic medical conditions; and 3) persons who live with or care for persons at high risk (e.g., health-care workers and household members who have frequent contact with persons at high risk and can transmit influenza to persons at high risk). Vaccination is associated with reductions in influenza-related respiratory illness and physician visits among all age groups, hospitalization and death among persons at high risk, otitis media among children, and work absenteeism among adults (9--18). Although influenza vaccination levels increased substantially during the 1990s, further improvements in vaccine coverage levels are needed, chiefly among persons aged <65 years at high risk. The ACIP recommends using strategies to improve vaccination levels, including using reminder/recall systems and standing orders programs (19,20). Although influenza vaccination remains the cornerstone for the control and treatment of influenza, information is also presented regarding antiviral medications, because these agents are an adjunct to vaccine. Primary Changes and Updates in the RecommendationsThe 2002 recommendations include five principal changes or updates, as follows:

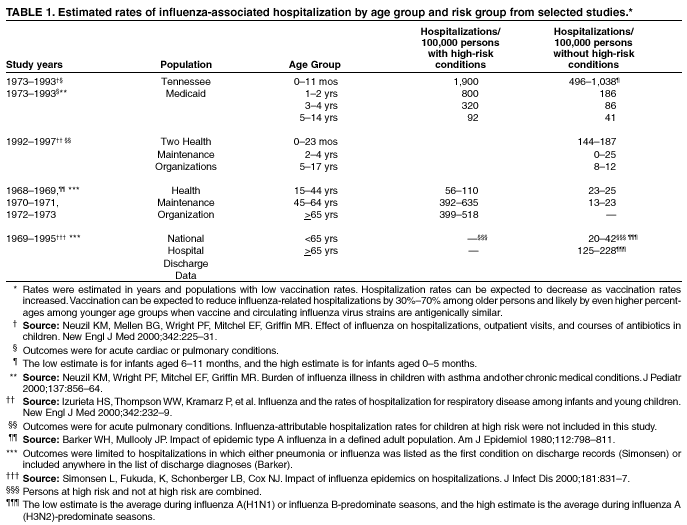

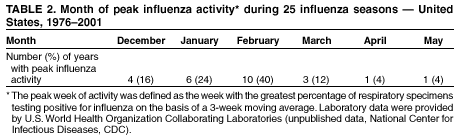

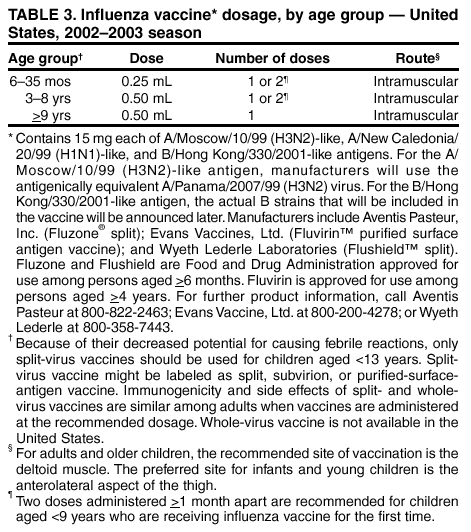

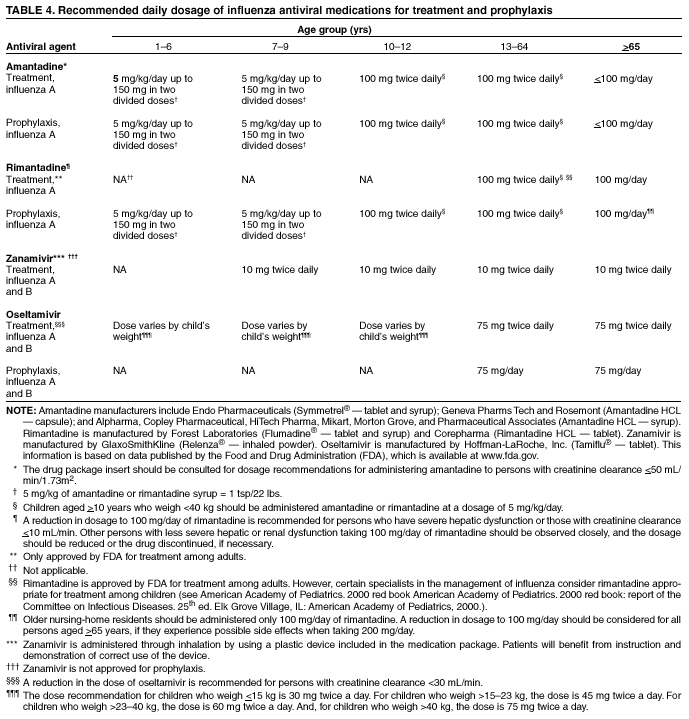

Influenza and Its BurdenBiology of Influenza Influenza A and B are the two types of influenza viruses that cause epidemic human disease (21). Influenza A viruses are further categorized into subtypes on the basis of two surface antigens: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). Influenza B viruses are not categorized into subtypes. Since 1977, influenza A (H1N1) viruses, influenza A (H3N2) viruses, and influenza B viruses have been in global circulation. Influenza A (H1N2) viruses that probably emerged after genetic reassortment between human A (H3N2) and A (H1N1) viruses have been detected recently in many countries. Both influenza A and B viruses are further separated into groups on the basis of antigenic characteristics. New influenza virus variants result from frequent antigenic change (i.e., antigenic drift) resulting from point mutations that occur during viral replication. Influenza B viruses undergo antigenic drift less rapidly than influenza A viruses. A person's immunity to the surface antigens, especially hemagglutinin, reduces the likelihood of infection and severity of disease if infection occurs (22). Antibody against one influenza virus type or subtype confers limited or no protection against another. Furthermore, antibody to one antigenic variant of influenza virus might not protect against a new antigenic variant of the same type or subtype (23). Frequent development of antigenic variants through antigenic drift is the virologic basis for seasonal epidemics and the reason for the incorporation of >1 new strains in each year's influenza vaccine. Clinical Signs and Symptoms of Influenza Influenza viruses are spread from person-to-person primarily through the coughing and sneezing of infected persons (21). The incubation period for influenza is 1--4 days, with an average of 2 days (24). Adults and children typically are infectious from the day before symptoms begin until approximately 5 days after illness onset. Children can be infectious for a longer period, and very young children can shed virus for <6 days before their illness onset. Severely immunocompromised persons can shed virus for weeks (25--27). Uncomplicated influenza illness is characterized by the abrupt onset of constitutional and respiratory signs and symptoms (e.g., fever, myalgia, headache, severe malaise, nonproductive cough, sore throat, and rhinitis) (28). Respiratory illness caused by influenza is difficult to distinguish from illness caused by other respiratory pathogens on the basis of symptoms alone (see Role of Laboratory Diagnosis). Reported sensitivities and specificities of clinical definitions for influenza-like illness that include fever and cough have ranged from 63% to 78% and 55% to 71%, respectively, compared with viral culture (29,30). Sensitivity and predictive value of clinical definitions can vary, depending on the degree of co-circulation of other respiratory pathogens and the level of influenza activity (31). Influenza illness typically resolves after a limited number of days for the majority of persons, although cough and malaise can persist for >2 weeks. Among certain persons, influenza can exacerbate underlying medical conditions (e.g., pulmonary or cardiac disease), lead to secondary bacterial pneumonia or primary influenza viral pneumonia, or occur as part of a coinfection with other viral or bacterial pathogens (32). Influenza infection has also been associated with encephalopathy, transverse myelitis, Reye syndrome, myositis, myocarditis, and pericarditis (32). Hospitalizations and Deaths from Influenza The risks for complications, hospitalizations, and deaths from influenza are higher among persons aged >65 years, very young children, and persons of any age with certain under-lying health conditions than among healthy older children and younger adults (1,2,7,9,33--35). Estimated rates of influenza-associated hospitalizations have varied substantially by age group in studies conducted during different influenza epidemics (Table 1). Among children aged 0--4 years, hospitalization rates have ranged from approximately 500/100,000 population for those with high-risk conditions to 100/100,000 population for those without high-risk conditions (36--39). Within the 0--4 age group, hospitalization rates are highest among children aged 0--1 years and are comparable to rates found among persons aged >65 years (38,39) (Table 1). During influenza epidemics from 1969--1970 through 1994--1995, the estimated overall number of influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States ranged from approximately 16,000 to 220,000/epidemic. An average of approximately 114,000 influenza-related excess hospitalizations occurred per year, with 57% of all hospitalizations occurring among persons aged <65 years. Since the 1968 influenza A (H3N2) virus pandemic, the greatest numbers of influenza-associated hospitalizations have occurred during epidemics caused by type A (H3N2) viruses, with an estimated average of 142,000 influenza-associated hospitalizations per year (40). Influenza-related deaths can result from pneumonia as well as from exacerbations of cardiopulmonary conditions and other chronic diseases. In studies of influenza epidemics occurring from 1972--1973 through 1994--1995, excess deaths (i.e., the number of influenza-related deaths above a projected baseline of expected deaths) occurred during 19 of 23 influenza epidemics (41) (unpublished data, Influenza Branch, Division of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases [DVRD], National Center for Infectious Diseases [NCID], CDC, 1998). During those 19 influenza seasons, estimated rates of influenza-associated deaths ranged from approximately 30 to >150 deaths/100,000 persons aged >65 years (unpublished data, Influenza Branch, DVRD, NCID, CDC, 1998). Older adults account for >90% of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (42). From 1972--1973 through 1994--1995, >20,000 influenza-associated deaths were estimated to occur during each of 11 different U.S. epidemics, and >40,000 influenza-associated deaths were estimated for each of 6 of these 11 epidemics (41) (unpublished data, Influenza Branch, DVRD, NCID, CDC, 1998). In the United States, pneumonia and influenza deaths might be increasing in part because the number of older persons is increasing (43). Options for Controlling InfluenzaIn the United States, the main option for reducing the impact of influenza is immunoprophylaxis with inactivated (i.e., killed virus) vaccine (see Recommendations for Using Influenza Vaccine). Vaccinating persons at high risk for complications each year before seasonal increases in influenza virus circulation is the most effective means of reducing the impact of influenza. Vaccination coverage can be increased by administering vaccine to persons during hospitalizations or routine health-care visits before the influenza season, rendering special visits to physicians' offices or clinics unnecessary. When vaccine and epidemic strains are well-matched, achieving increased vaccination rates among persons living in closed settings (e.g., nursing homes and other chronic-care facilities) and among staff can reduce the risk for outbreaks by inducing herd immunity (14). Vaccination of health-care workers and other persons in close contact with persons in groups at high risk can also reduce transmission of influenza and subsequent influenza-related complications. Using influenza-specific antiviral drugs for chemoprophylaxis or treatment of influenza is a key adjunct to vaccine (see Recommendations for Using Antiviral Agents for Influenza). However, antiviral medications are not a substitute for vaccination. Influenza vaccines are standardized to contain the hemagglutinins of strains (i.e., typically two type A and one type B), representing the influenza viruses likely to circulate in the United States in the upcoming winter. The vaccine is made from highly purified, egg-grown viruses that have been made noninfectious (i.e., inactivated) (44). Subvirion and purified surface-antigen preparations are available. Because the vaccine viruses are initially grown in embryonated hens' eggs, the vaccine might contain limited amounts of residual egg protein. Manufacturing processes differ by manufacturer. Manufacturers might use different compounds to inactivate influenza viruses and add antibiotics to prevent bacterial contamination. Package inserts should be consulted for additional information. Influenza vaccine distributed in the United States might also contain thimerosal, a mercury-containing compound, as the preservative (45). Thimerosal has been used as a preservative in vaccines since the 1930s. Although no evidence of harm caused by low levels of thimerosal in vaccines has been reported, in 1999, the U.S. Public Health Service and other organizations recommended that efforts be made to reduce the thimerosal content in vaccines to decrease total mercury exposure, chiefly among infants and pregnant woman (45,46). Since mid-2001, routinely administered, noninfluenza childhood vaccines for the U.S. market have been manufactured either without or with only trace amounts of thimerosal to provide a substantial reduction in the total mercury exposure from vaccines for children (47). For the 2002--2003 influenza season, a limited number of individually packaged doses (i.e., single-dose syringes) of reduced thimerosal-content influenza vaccine (<1 mcg thimerosal/0.5 mL-dose) will be available. Thus far, reduced thimerosal content vaccine is available from one manufacturer, Evans Vaccines. This manufacturer's vaccine is approved for use in persons aged >4 years (see Vaccine Use for Young Children, By Manufacturer). Multidose vials and single-dose syringes of influenza vaccine containing approximately 25 mcg thimerosal/0.5 mL-dose are also available as they have been in past years. Because of the known risks for severe illness from influenza infection and the benefits of vaccination, and because a substantial safety margin has been incorporated into the health guidance values for organic mercury exposure, the benefit of influenza vaccine with reduced or standard thimerosal content outweighs the theoretical risk, if any, from thimerosal (45,48). The removal of thimerosal from other vaccines further reduces the theoretical risk from thimerosal in influenza vaccines. The trivalent influenza vaccine recommended for the 2002--2003 season includes A/Moscow/10/99 (H3N2)-like, A/New Caledonia/20/99 (H1N1)-like, and B/Hong Kong/330/2001-like antigens. For the A/Moscow/10/99 (H3N2)-like antigen, manufacturers will use the antigenically equivalent A/Panama/2007/99 (H3N2) virus. For the B/Hong Kong/330/2001-like antigen, the actual B strains that will be included in the vaccine will be announced later. These viruses will be used because of their growth properties and because they are representative of influenza viruses likely to circulate in the United States during the 2002--2003 influenza season. Because circulating influenza A (H1N2) viruses are a reasortant of influenza A (H1N1) and (H3N2) viruses, antibody directed against influenza A (H1N1) and influenza (H3N2) vaccine strains will provide protection against circulating influenza A (H1N2) viruses. Effectiveness of Inactivated Influenza Vaccine The effectiveness of influenza vaccine depends primarily on the age and immunocompetence of the vaccine recipient and the degree of similarity between the viruses in the vaccine and those in circulation. The majority of vaccinated children and young adults develop high postvaccination hemagglutination-inhibition antibody titers (49--51). These antibody titers are protective against illness caused by strains similar to those in the vaccine (50--53). When the vaccine and circulating viruses are antigenically similar, influenza vaccine prevents influenza illness among approximately 70%--90% of healthy adults aged <65 years (10,13,54,55). Vaccination of healthy adults also has resulted in decreased work absenteeism and decreased use of health-care resources, including use of antibiotics, when the vaccine and circulating viruses are well-matched (10--13,55,56). Children as young as age 6 months can develop protective levels of antibody after influenza vaccination (49,50,57--60), although the antibody response among children at high risk might be lower than among healthy children (61,62). In a randomized study among children aged 1--15 years, inactivated influenza vaccine was 77%--91% effective against influenza respiratory illness and was 44%--49%, 74%--76%, and 70%--81% effective against influenza seroconversion among children aged 1--5, 6--10, and 11--15 years, respectively (51). One study (63) reported a vaccine efficacy of 56% against influenza illness among healthy children aged 3--9 years, and another study (64) found vaccine efficacy of 22%--54% and 60%--78% among children with asthma aged 2--6 years and 7--14 years, respectively. A 2-year randomized study of children aged 6--24 months determined that >89% of children seroconverted to all three vaccine strains during both years; vaccine efficacy was 66% (95% confidence intervals [CI] = 34% and 82%) against culture-confirmed influenza during year 1 among 411 children and was --7% (95% CI = --247% and 67%) during year 2 among 375 children. However, no overall reduction in otitis media was reported (65). Other studies report that using trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine decreases the incidence of influenza-associated otitis media among young children by approximately 30% (17,18). Older persons and persons with certain chronic diseases might develop lower postvaccination antibody titers than healthy young adults and thus can remain susceptible to influenza-related upper respiratory tract infection (66--68). A randomized trial among noninstitutionalized persons aged >60 years reported a vaccine efficacy of 58% against influenza respiratory illness, but indicated that efficacy might be lower among those aged >70 years (69). The vaccine can also be effective in preventing secondary complications and reducing the risk for influenza-related hospitalization and death (14--16,70). Among elderly persons living outside nursing homes or similar chronic-care facilities, influenza vaccine is 30%--70% effective in preventing hospitalization for pneumonia and influenza (16,71). Among elderly persons residing in nursing homes, influenza vaccine is most effective in preventing severe illness, secondary complications, and deaths. Among this population, the vaccine can be 50%--60% effective in preventing hospitalization or pneumonia and 80% effective in preventing death, although the effectiveness in preventing influenza illness often ranges from 30% to 40% (72,73). Cost-Effectiveness of Influenza Vaccine Influenza vaccination can reduce both health-care costs and productivity losses associated with influenza illness. Economic studies of influenza vaccination of persons aged >65 years conducted in the United States have reported overall societal cost-savings and substantial reductions in hospitalization and death (16,71,74). Studies of adults aged <65 years have reported that vaccination can reduce both direct medical costs and indirect costs from work absenteeism (9,11--13,55). Reductions of 34%--44% in physician visits, 32%--45% in lost workdays (11,13), and 25% in antibiotic use for influenza-associated illnesses have been reported (13). One cost-effectiveness analysis estimated a cost of approximately $60--$4,000/illness averted among healthy persons aged 18--64 years, depending on the cost of vaccination, the influenza attack rate, and vaccine effectiveness against influenza-like illness (55). Another cost-benefit economic model estimated an average annual savings of $13.66/person vaccinated (75). In the second study, 78% of all costs prevented were costs from lost work productivity, whereas the first study did not include productivity losses from influenza illness. Economic studies specifically evaluating the cost-effectiveness of vaccinating persons aged 50--64 years are not available, and the number of studies that examine the economics of routinely vaccinating children are limited (9,76--78). However, in a study that included all age groups, cost-utility improved with increasing age and among those with chronic medical conditions (9). Among persons aged >65 years, vaccination resulted in a net savings per quality-adjusted-life-year (QALY) gained and resulted in costs of $23--$256/QALY among younger age groups. Additional studies of the relative cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of influenza vaccination among children and among adults aged <65 years are needed and should be designed to account for year-to-year variations in influenza attack rates, illness severity, and vaccine efficacy when evaluating the long-term costs and benefits of annual vaccination. Vaccination Coverage Levels Among persons aged >65 years, influenza vaccination levels increased from 33% in 1989 (79) to 66% in 1999 (80), surpassing the Healthy People 2000 goal of 60% (81). Although 1999 influenza vaccination coverage reached the highest levels recorded among black, Hispanic, and white populations, vaccination levels among blacks and Hispanics continue to lag behind those among whites (80,82). In 1999, the influenza vaccination rates among persons aged >65 years were 68% among non-Hispanic whites, 50% among non-Hispanic blacks, and 55% among Hispanics (80). Possible reasons for the increase in influenza vaccination levels among persons aged >65 years through 1999 include greater acceptance of preventive medical services by practitioners, increased delivery and administration of vaccine by health-care providers and sources other than physicians, new information regarding influenza vaccine effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and safety, and the initiation of Medicare reimbursement for influenza vaccination in 1993 (9,15,16,72,73,83,84). Influenza vaccination levels among persons interviewed during 2000 were not substantially different from 1999 levels among persons aged >65 years (64% in 2000 versus 66% in 1999) and persons aged 50--64 years (35% in 2000 versus 34% in 1999) (80). The percentage of adults interviewed during the first quarter of 2001 who reported influenza vaccination during the past 12 months was lower than the percentage reported by adults interviewed during the first quarter of 2000 (63% versus 68% among those aged >65 years; 32% versus 37% among those aged 50--64 years). Delays in influenza vaccine supply during fall 2000 probably contributed to these declines in vaccination levels (see Vaccine Supply). Continued annual monitoring is needed to determine the effects of vaccine supply delays and other factors on vaccination coverage among persons aged >50 years. The Healthy People 2010 objective is to achieve vaccination coverage for 90% of persons aged >65 years (85). Additional strategies are needed to achieve this Healthy People 2010 objective in all segments of the population and to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in vaccine coverage. In 1997 and 1998, vaccination rate estimates among nursing home residents were 64%--82% and 83%, respectively (86,87). The Healthy People 2010 goal is to achieve influenza vaccination of 90% of nursing home residents, an increase from the Healthy People 2000 goal of 80% (81,85). In 2000, the overall vaccination rate for adults aged 18--64 years with high-risk conditions was 32%, far short of the Healthy People 2000 goal of 60% (unpublished data, National Immunization Program [NIP], CDC, 2000) (81). Among persons aged 50--64 years, 44% of those with chronic medical conditions and 31% of those without chronic medical conditions received influenza vaccine. Only 25% of adults aged <50 years with high-risk conditions were vaccinated. Reported vaccination rates of children at high risk are low. One study conducted among patients in health maintenance organizations reported influenza vaccination rates ranging from 9% to 10% among children with asthma (88), and a rate of 25% was reported among children with severe-to-moderate asthma who attended an allergy and immunology clinic (89). However, a study conducted in a pediatric clinic demonstrated an increase in the vaccination rate of children with asthma or reactive airways disease of 5%--32% after implementing a reminder/recall system (90). Increasing vaccination coverage among persons who have high-risk conditions and are aged <65 years, including children at high risk, is the highest priority for expanding influenza vaccine use. Annual vaccination is recommended for health-care workers. Nonetheless, the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) indicated vaccination rates of only 34% and 38% among health-care workers in the 1997 and 2000 surveys, respectively (91) (unpublished NHIS data, NIP, CDC, 2002). Vaccination of health-care workers has been associated with reduced work absenteeism (10) and fewer deaths among nursing home patients (92,93). Limited information is available regarding the use of influenza vaccine among pregnant women. Among women aged 18--44 years without diabetes responding to the 1999 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, those reporting they were pregnant were less likely to report influenza vaccination during the past 12 months (9.6%) than those not pregnant (15.7%). Vaccination coverage among pregnant women did not substantially change during 1997--1999, whereas coverage among nonpregnant women increased from 14.4% in 1997. Similar results were determined by using the 1997--2000 NHIS data, excluding pregnant women who reported diabetes, heart disease, lung disease, and other selected high-risk conditions (unpublished NHIS data, NIP, CDC, 2002). Although not directly measuring influenza vaccination among women who were past the second trimester of pregnancy during influenza season, these data indicate low compliance with the ACIP recommendations for pregnant women (94). In a study of influenza vaccine acceptance by pregnant women, 71% who were offered the vaccine chose to be vaccinated (95). However, a 1999 survey of obstetricians and gynecologists determined that only 39% gave influenza vaccine to obstetric patients, although 86% agree that pregnant women's risk for influenza-related morbidity and mortality increases during the last two trimesters (96). Recommendations for Using Influenza VaccineInfluenza vaccine is strongly recommended for any person aged >6 months who is at increased risk for complications from influenza. In addition, health-care workers and other persons (including household members) in close contact with persons at high risk should be vaccinated to decrease the risk for transmitting influenza to persons at high risk. Influenza vaccine also can be administered to any person aged >6 months to reduce the probability of becoming infected with influenza. Target Groups for VaccinationPersons at Increased Risk for Complications Vaccination is recommended for the following groups of persons who are at increased risk for complications from influenza:

Approximately 35 million persons in the United States are aged >65 years; an additional 10--14 million adults aged 50--64 years, 15--18 million adults aged 18--49 years, and 8 million children aged 6 months--17 years have >1 medical conditions that are associated with an increased risk for influenza-related complications (unpublished data, NIP, CDC, 2002). Persons Aged 50--64 Years Vaccination is recommended for persons aged 50--64 years because this group has an increased prevalence of persons with high-risk conditions. Approximately 43 million persons in the United States are aged 50--64 years, and 10--14 million (24%--32%) have >1 high-risk medical conditions (unpublished data, NIP, CDC, 2002). Influenza vaccine has been recommended for this entire age group to increase the low vaccination rates among persons in this age group with high-risk conditions. Age-based strategies are more successful in increasing vaccine coverage than patient-selection strategies based on medical conditions. Persons aged 50--64 years without high-risk conditions also receive benefit from vaccination in the form of decreased rates of influenza illness, decreased work absenteeism, and decreased need for medical visits and medication, including antibiotics (10--13). Further, 50 years is an age when other preventive services begin and when routine assessment of vaccination and other preventive services has been recommended (97,98). Persons Who Can Transmit Influenza to Those at High Risk Persons who are clinically or subclinically infected can transmit influenza virus to persons at high risk for complications from influenza. Decreasing transmission of influenza from caregivers to persons at high risk might reduce influenza-related deaths among persons at high risk. Evidence from two studies indicates that vaccination of health-care workers is associated with decreased deaths among nursing home patients (92,93). Vaccination of health-care workers and others in close contact with persons at high risk, including household members, is recommended. The following groups should be vaccinated:

In addition, because children aged 0--23 months are at increased risk for influenza-related hospitalization (37--39), vaccination is encouraged for their household contacts and out-of-home caretakers, particularly for contacts of children aged 0--5 months because influenza vaccines have not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use among children aged <6 months (see Healthy Young Children). Additional Information Regarding Vaccination of Specific PopulationsPregnant Women Influenza-associated excess deaths among pregnant women were documented during the pandemics of 1918--1919 and 1957--1958 (99--102). Case reports and limited studies also indicate that pregnancy can increase the risk for serious medical complications of influenza as a result of increases in heart rate, stroke volume, and oxygen consumption; decreases in lung capacity; and changes in immunologic function (103--106). A study of the impact of influenza during 17 interpandemic influenza seasons demonstrated that the relative risk for hospitalization for selected cardiorespiratory conditions among pregnant women enrolled in Medicaid increased from 1.4 during weeks 14--20 of gestation to 4.7 during weeks 37--42 in comparison with women who were 1--6 months postpartum (107). Women in their third trimester of pregnancy were hospitalized at a rate (i.e., 250/100,000 pregnant women) comparable with that of nonpregnant women who had high-risk medical conditions. By using data from this study, researchers estimated that an average of 1--2 hospitalizations could be prevented for every 1,000 pregnant women vaccinated. Because of the increased risk for influenza-related complications, women who will be beyond the first trimester of pregnancy (>14 weeks of gestation) during the influenza season should be vaccinated. Certain providers prefer to administer influenza vaccine during the second trimester to avoid a coincidental association with spontaneous abortion, which is common in the first trimester, and because exposures to vaccines traditionally have been avoided during the first trimester (108). Pregnant women who have medical conditions that increase their risk for complications from influenza should be vaccinated before the influenza season, regardless of the stage of pregnancy. A study of influenza vaccination of >2,000 pregnant women demonstrated no adverse fetal effects associated with influenza vaccine (109). However, additional data are needed to confirm the safety of vaccination during pregnancy. The majority of influenza vaccine distributed in the United States contains thimerosal, a mercury-containing compound, as a preservative, but influenza vaccine with reduced thimerosal content might be available in limited quantities (see Influenza Vaccine Composition). Thimerosal has been used in U.S. vaccines since the 1930s. No data or evidence exists of any harm caused by the level of mercury exposure that might occur from influenza vaccination. Because pregnant women are at increased risk for influenza-related complications and because a substantial safety margin has been incorporated into the health guidance values for organic mercury exposure, the benefit of influenza vaccine with reduced or standard thimerosal content outweighs the potential risk, if any, for thimerosal (45,48). Persons Infected with HIV Limited information is available regarding the frequency and severity of influenza illness or the benefits of influenza vaccination among persons with HIV infection (110,111). However, a retrospective study of young and middle-aged women enrolled in Tennessee's Medicaid program found that the attributable-risk for cardiopulmonary hospitalizations among women with HIV infection was higher during influenza seasons than during the peri-influenza periods. The risk for hospitalization was higher for HIV-infected women than for women with other well-recognized high-risk conditions, including chronic heart and lung diseases (112). Another study estimated that the risk for influenza-related death was 9.4--14.6/10,000 persons with AIDS, compared with rates of 0.09--0.10/10,000 among all persons aged 25--54 years and 6.4--7.0/10,000 among persons aged >65 years (113). Other reports demonstrate that influenza symptoms might be prolonged and the risk for complications from influenza increased for certain HIV-infected persons (114--116). Influenza vaccination has been demonstrated to produce substantial antibody titers against influenza among vaccinated HIV-infected persons who have minimal acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related symptoms and high CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell counts (117--120). A limited, randomized, placebo-controlled trial determined that influenza vaccine was highly effective in preventing symptomatic, laboratory-confirmed influenza infection among HIV-infected persons with a mean of 400 CD4+ T-lymphocyte cells/mm3; a limited number of persons with CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell counts of <200 were included in that study (111). A nonrandomized study among HIV-infected persons determined that influenza vaccination was most effective among persons with >100 CD4+ cells and among those with <30,000 viral copies of HIV type 1/mL (116). Among patients who have advanced HIV disease and low CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell counts, influenza vaccine might not induce protective antibody titers (119,120); a second dose of vaccine does not improve the immune response in these persons (120,121). One study reported that HIV RNA levels increased transiently in one HIV-infected patient after influenza infection (122). Studies have demonstrated a transient (i.e., 2--4-week) increase in replication of HIV-1 in the plasma or peripheral blood mononuclear cells of HIV-infected persons after vaccine administration (119,123). Other studies using similar laboratory techniques have not documented a substantial increase in the replication of HIV (124--126). Deterioration of CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell counts or progression of HIV disease have not been demonstrated among HIV-infected persons after influenza vaccination compared with unvaccinated persons (120,127). Limited information is available concerning the effect of antiretroviral therapy on increases in HIV RNA levels after either natural influenza infection or influenza vaccination (110,128). Because influenza can result in serious illness and because influenza vaccination can result in the production of protective antibody titers, vaccination will benefit HIV-infected patients, including HIV-infected pregnant women. Breast-Feeding Mothers Influenza vaccine does not affect the safety of mothers who are breast-feeding or their infants. Breast-feeding does not adversely affect the immune response and is not a contraindication for vaccination. The risk for exposure to influenza during travel depends on the time of year and destination. In the tropics, influenza can occur throughout the year. In the temperate regions of the Southern Hemisphere, the majority of influenza activity occurs during April--September. In temperate climate zones of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, travelers also can be exposed to influenza during the summer, especially when traveling as part of organized tourist groups that include persons from areas of the world where influenza viruses are circulating. Persons at high risk for complications of influenza who were not vaccinated with influenza vaccine during the preceding fall or winter should consider receiving influenza vaccine before travel if they plan to