|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Malaria Surveillance --- United States, 2007Sonja Mali, MPH

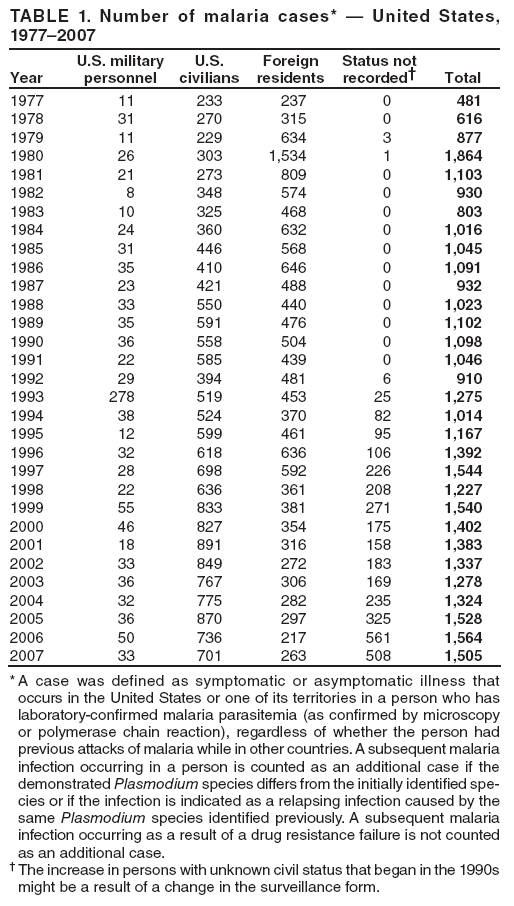

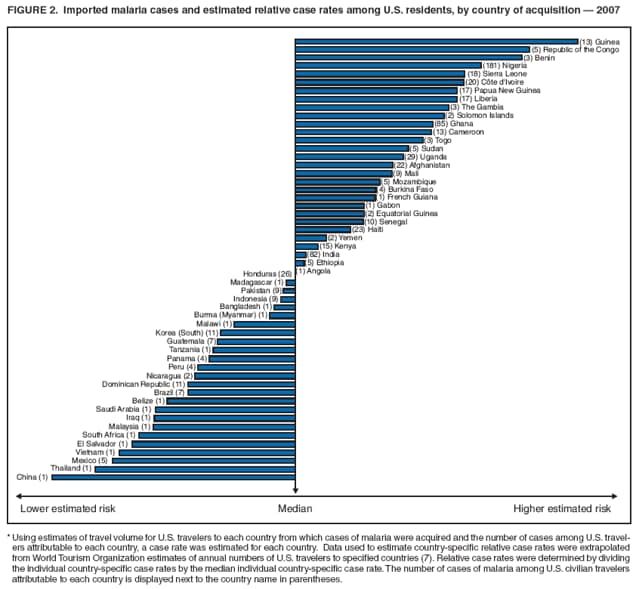

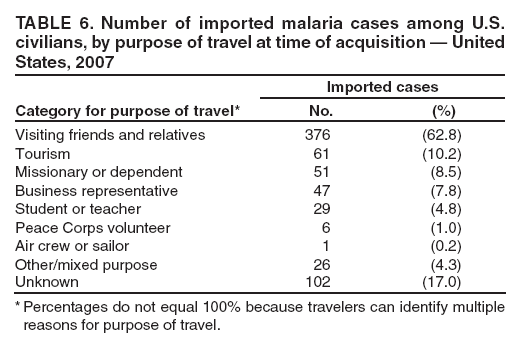

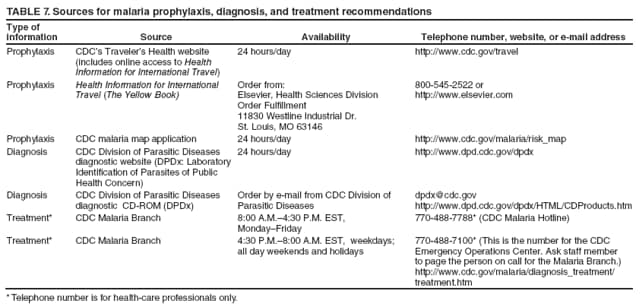

Corresponding author: Sonja Mali, MPH, Division of Parasitic Diseases, National Center for Zoonotic, Vector-Borne, and Enteric Diseases, CDC, 4770 Buford Hwy., N.E., MS F-22, Atlanta, GA 30341. Telephone: 770-488-7757; Fax: 770-488-4465; E-mail: [email protected]. AbstractProblem/Condition: Malaria in humans is caused by intraerythrocytic protozoa of the genus Plasmodium. These parasites are transmitted by the bite of an infective female Anopheles mosquito. The majority of malaria infections in the United States occur among persons who have traveled to areas with ongoing malaria transmission. In the United States, cases can occur through exposure to infected blood products, congenital transmission, or local mosquitoborne transmission. Malaria surveillance is conducted to identify episodes of local transmission and to guide prevention recommendations for travelers. Period Covered: This report summarizes cases in persons with onset of illness in 2007 and summarizes trends during previous years. Description of System: Malaria cases confirmed by blood film, rapid diagnostic tests, or polymerase chain reaction are mandated to be reported to local and state health departments by health-care providers or laboratory staff members. Case investigations are conducted by local and state health departments, and reports are transmitted to CDC through the National Malaria Surveillance System, the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, and direct CDC consultations. Data from these reporting systems are the basis for this report. Results: CDC received reports of 1,505 cases of malaria among persons in the United States, including one transfusion-related case and one fatal case, with onset of symptoms in 2007; 1,564 cases were reported for 2006. P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, and P. ovale were identified in 43.4%, 20.3%, 2.0%, and 3.5% of cases, respectively. Nine patients (0.6%) were infected by two or more species. The infecting species was unreported or undetermined in 30.2% of cases. Based on estimated volume of travel, the highest estimated relative case rates of malaria among travelers occurred among those returning from countries in West Africa. Of 701 U.S. civilians who acquired malaria abroad and for whom chemoprophylaxis information was known, 441 (62.9%) reported that they had not followed a chemoprophylactic drug regimen recommended by CDC for the area to which they had traveled. Twenty-four cases were reported in pregnant women; none had adhered to a complete prevention drug regimen. One death was reported in a person infected with P. vivax. Interpretation: No significant change in the number of malaria cases occurred from 2006 to 2007. No change was observed in the proportion of cases by species causing the infection. U.S. civilians traveling to countries in West Africa had the highest estimated relative case rates. In the majority of reported cases, U.S. civilians who acquired infection abroad had not adhered to a chemoprophylaxis regimen that was appropriate for the country where they acquired malaria. Public Health Actions: Persons at risk for malaria infection should take one of the recommended chemoprophylaxis regimens appropriate for the region of travel and use personal protection measures to prevent mosquito bites. Any person who has been to a malarious area and who subsequently has a fever or influenza-like symptoms should seek medical care immediately and report their travel history to the clinician; investigation should always include blood-film tests for malaria with immediately available results. Malaria infections can be fatal if not diagnosed and treated promptly. Recommendations concerning malaria prevention are available from CDC at http://wwwn.cdc.gov/travel/contentdiseases.aspx#malaria or by calling the CDC Malaria Hotline (telephone: 770-488-7788). Recommendations concerning malaria treatment are available at http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/diagnosis_treatment/treatment.htm or by calling the Malaria Hotline. IntroductionMalaria in humans is caused by infection with one or more of several species of Plasmodium (i.e., P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, and occasionally other Plasmodium species). The infection is transmitted by the bite of an infective female Anopheles species mosquito. P. falciparum and P. vivax species cause the most infections worldwide. P. falciparum is the species that most commonly causes severe, potentially fatal malaria. Worldwide, an estimated 350--500 million clinical cases and approximately 1 million deaths caused by malaria occur annually, primarily among children aged <5 years living in sub-Saharan Africa (1). P. vivax and P. ovale have dormant liver-stage parasites, which can reactivate and cause malaria several months or years after the infecting mosquito bite. P. malariae can result in long-lasting infections that, if untreated, can persist asymptomatically in the human host for years, even a lifetime (1). P. knowlesi, a parasite of Old World monkeys, has been documented as a cause of human infections and some fatalities in Southeast Asia; investigations are ongoing to determine the extent of transmission to humans (2,3). A total of 49% of the world population lives in areas where malaria is transmitted (i.e., 109 countries in parts of Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, Central and South America, Caribbean, and Oceania). Before the 1950s, malaria was endemic throughout the southeastern United States; an estimated 600,000 cases occurred in the United States in 1914 (4). During the late 1940s, a combination of improved housing and socioeconomic conditions, environmental management, vector-control efforts, and case management was successful at interrupting malaria transmission in the United States. Since then, malaria case surveillance has been maintained to detect locally acquired cases that could indicate the reintroduction of transmission and to monitor patterns of resistance to antimalarial drugs. Anopheline mosquitoes remain seasonally present in all states and territories except Hawaii. The majority of reported malaria cases diagnosed each year in the United States are imported from regions where malaria transmission is known to occur, although congenital infections and infections resulting from exposure to blood or blood products are also reported in the United States. In addition, a limited number of cases are occasionally reported that might have been acquired through local mosquitoborne transmission (5). State and local health departments and CDC investigate malaria cases acquired in the United States, and CDC analyzes data from reported cases to detect trends in acquisition. This information is used to guide malaria prevention recommendations for international travelers. The signs and symptoms of malaria illness vary, but the majority of patients have fever. Other common symptoms include headache, back pain, chills, increased sweating, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and cough. The diagnosis of malaria should always be considered for persons with these symptoms who have traveled to an area with known malaria transmission. Malaria also should be considered in the differential diagnosis of persons who have fever of unknown origin, regardless of their travel history. Untreated P. falciparum infections can rapidly progress to coma, renal failure, pulmonary edema, and death. This report summarizes malaria cases reported to CDC among persons with onset of symptoms in 2007. MethodsData Sources Malaria case data are reported to the National Malaria Surveillance System (NMSS) and the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) (6). Although both systems rely on passive reporting, the numbers of reported cases might differ because of differences in collection and transmission of data. A substantial difference between the data collected in these two systems is that NMSS receives more detailed clinical and epidemiologic data regarding each case (e.g., information concerning the area to which the infected person has traveled). Malaria cases can be reported to CDC through NMSS, NNDSS, or a direct consultation with CDC; cases identified through these various paths are compared and compiled, duplicates are eliminated, and cases are analyzed. This report presents data on the aggregate of cases reported to CDC through all reporting systems. Cases of malaria confirmed by blood film, a rapid diagnostic test (RDT), or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) among civilians and military personnel are identified by health-care providers or laboratories.* Each confirmed malaria case is reported to local or state health departments and to CDC on a uniform case-report form that contains clinical, laboratory, and epidemiologic information. CDC reviews all report forms when received and requests additional information from the reporting provider or state if necessary (e.g., when no recent travel to a malarious country is reported). Other cases are reported by telephone to CDC directly by health-care providers, usually when they are seeking assistance with diagnosis or treatment. Information regarding cases reported directly to CDC is shared with relevant state health departments. All cases that have been reported as acquired in the United States are investigated further, including all induced and congenital cases and possible introduced or cryptic cases. Information derived from uniform case report forms is entered into a database and analyzed annually. An estimated case rate for each country was determined using estimates of travel volume for U.S. travelers to each country where cases of malaria were acquired and the number of cases among U.S. travelers attributable to each country. Data used to estimate country-specific relative case rates were extrapolated from World Tourism Organization estimates of annual numbers of U.S. travelers to specified countries (7). Estimated relative case rates were determined by dividing the individual country-specific case rates by the median individual country-specific case rate. DefinitionsThe following definitions are used in this report:

This report also uses terminology derived from the recommendations of the World Health Organization (8). Definitions of the following terms are included for reference:

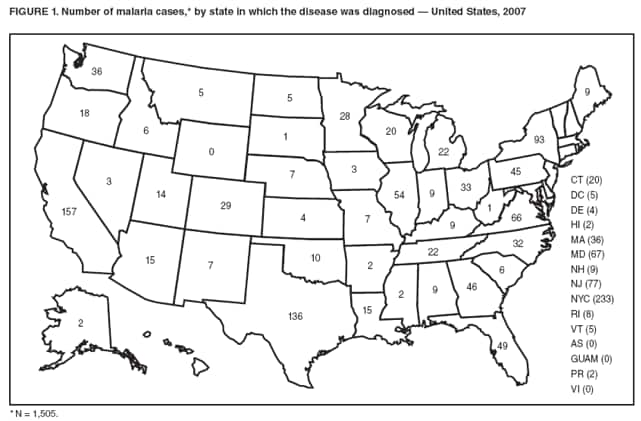

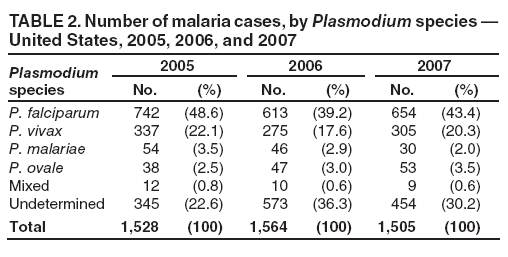

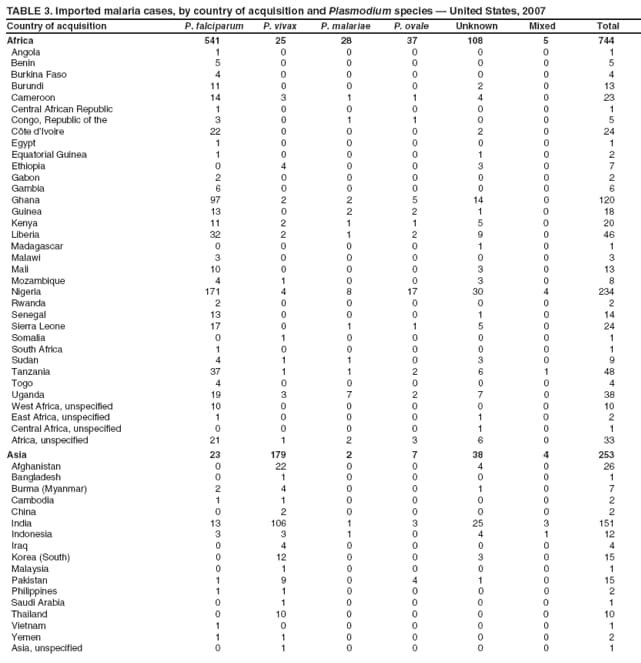

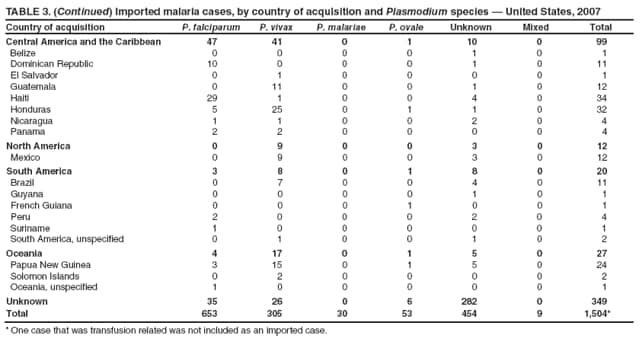

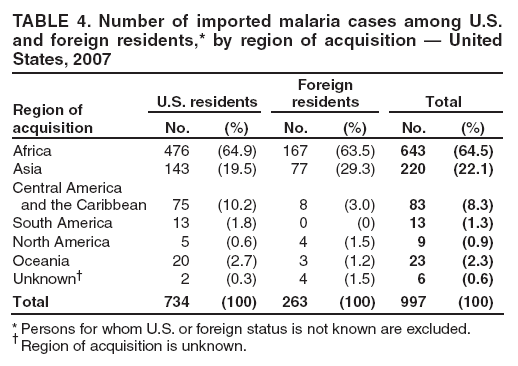

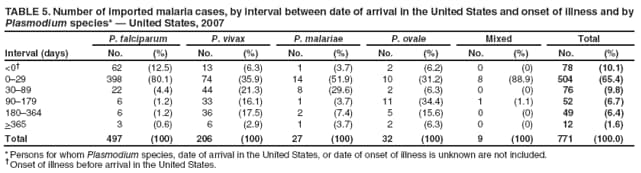

Laboratory Diagnosis of MalariaThe early and prompt diagnosis of malaria requires that physicians obtain a travel history from every febrile patient. Malaria should be included in the differential diagnosis of every febrile patient who has traveled to a malarious area. If malaria is suspected, a Giemsa-stained film of the patient's peripheral blood should be examined for parasites as soon as possible. Thick and thin blood films must be prepared correctly because diagnostic accuracy depends on blood-film quality and examination by experienced laboratory personnel (9). Some reference laboratories and health departments have the capacity to perform PCR diagnosis of malaria, although PCR is generally reserved for cases for which blood-film diagnosis of malaria or species determination is inadequate. PCR results are also often not available quickly enough to be useful in the initial diagnosis of a patient with malaria. An RDT, BinaxNOW Malaria, which detects circulating malaria-specific antigens, became available for use in the United States on June 13, 2007. The test is the first malaria RDT authorized for use in the United States and is only approved for use by hospital and commercial laboratories, not by individual clinicians or the general public. Use of RDTs in the United States can decrease the amount of time required to determine whether a patient is infected with malaria but does not eliminate the need for the standard tests (10). Positive and negative RDTs must be confirmed by microscopy or PCR. RDTs are generally less sensitive than blood films and do not quantify malaria parasites (11). ResultsGeneral Surveillance For 2007, CDC received 1,505 reports of cases of malaria occurring among persons in the United States and its territories. A total of 734 cases occurred among U.S. residents, 263 cases among foreign residents and 508 cases among persons with unknown resident status. Of the 734 cases reported among U.S. residents, 50.1% were among blacks, 27.2% among whites, 10.9% among Asians, and 4% among Hispanics; 67% of the U.S. resident cases were among males. The 1,505 cases reported in 2007 is not significantly different from the 1,564 cases reported in 2006 (9) (Table 1) (chi-square test; p = 0.25). After a significant increase in cases from 2003 to 2004 (chi-square test; p = 0.002), the number of malaria cases appears to have plateaued beginning in 2004; during 2004--2007, no statistically significant change occurred in the number of reported cases (chi-square test; p = 0.21). Plasmodium SpeciesOf the 1,505 cases reported in 2007, the infecting species of Plasmodium was identified and reported in 1,051 (69.8%) cases. P. falciparum and P. vivax accounted for the majority of infections and were identified in 62.2% and 29.0% of infected persons with species identified, respectively. The number of reported cases of P. falciparum and P. vivax remained stable during 2005--2007 (Table 2). Among 983 cases for which both the region of acquisition and the infecting species were known, P. falciparum accounted for 85.1% of infections acquired in Africa, 45.4% in the Americas, 18.2% in Oceania, and 10.7% in Asia (Table 3). Infections attributed to P. vivax accounted for 3.9% acquired in Africa, 52.7% in the Americas, 77.3% in Oceania, and 83.2% in Asia. Region of Acquisition and DiagnosisAll cases were reported as imported cases, except for one transfusion-related case. Of 1,155 imported cases for which the region of acquisition was known, 744 (64.4%) were acquired in Africa, 253 (21.9%) in Asia, 131 (11.3%) in the Americas, and 27 (2.3%) in Oceania. Countries in West Africa accounted for 545 (73.3%) cases acquired in Africa, and India accounted for 151 (59.7%) cases acquired in Asia. In the Americas, 12 (9.2%) cases were acquired in North America, all of which were acquired in Mexico. A combined 99 (78.6%) cases were acquired in Central America and the Caribbean (Belize, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama), of which 66% of the cases were acquired in the Caribbean. Twenty (17.3%) cases were acquired in South America (Brazil, Guyana, French Guiana, Peru, and Suriname). Information regarding region of acquisition was missing for 349 (23.2%) imported cases (Table 3). In the United States, six jurisdictions accounted for 50.7% of the reported cases: New York City (n = 233), California (n = 157), Texas (n = 136), New York (n = 93), New Jersey (n = 77), and Maryland (n = 67) (Figure 1). Compared with 2006, the states and regions with the most significant change in reported malaria burden in 2007 were New York City, Georgia, and Alaska. The number of cases reported in New York City increased from 174 cases in 2006 to 233 cases in 2007. Cases in Georgia decreased by almost half, from 90 in 2006 to 46 in 2007, and Alaska reported a significant decrease from 23 cases (all among military personnel) in 2006 to two cases in 2007. No cases from Alaska among military personnel were documented in 2007. Imported Malaria by Resident StatusOf 997 imported malaria cases among persons with known resident status, 734 (73.6%) occurred among U.S. residents, and 263 (26.4%) occurred among residents of other countries. Of the 734 imported malaria cases among U.S. residents, 476 (64.9%) were acquired in Africa, 143 (19.5%) were acquired in Asia, and 75 (10.2%) were acquired in Central American and Caribbean regions (Table 4). Of the 263 imported cases among foreign residents, 167 (63.5%) were acquired in Africa. Among the 167 foreign residents who acquired malaria in Africa and for whom purpose of travel was known, 114 (68.3%) reported being recent immigrants or refugees, and 21 (12.6%) reported visiting friends and relatives in the United States. A total of 61 cases were in foreign residents who traveled from Tanzania and Burundi to the United States; reason for travel was known for 58 persons, among whom 57 were reported as being recent immigrants or refugees, and one was reported as visiting friends and relatives. In 2006, no foreign cases were reported from Tanzania or Burundi (9). Estimated Relative Case Rates Among U.S. ResidentsUsing estimates of travel volume for U.S. travelers to each country from which cases of malaria were acquired and the number of cases among U.S. travelers attributable to each country, a case rate was estimated for each country. In 2007, the countries with the lowest estimated case rates of malaria among U.S. travelers were China and Thailand (Figure 2). Other countries with low estimated relative case rates included Mexico, Vietnam, and South Africa. In many of these countries, malaria risk areas are localized in small geographic areas of the country. Countries with estimated relative case rates in the middle range included India, Honduras, Angola, and Pakistan, which have more homogenous malaria transmission throughout the country. Estimated relative case rates were highest in West African countries and Oceania, including Republic of the Congo, Benin, Papua New Guinea, and Solomon Islands. These high estimated case rates likely reflect not only widespread transmission areas but also higher transmission intensity (1). Interval Between Arrival in the United States and IllnessBoth the 1) interval between the date of arrival in the United States and onset of illness and 2) infecting Plasmodium species were known for 771 (51.2%) of the imported malaria cases (Table 5). Symptoms began before arrival in the United States in 78 (10.1%) persons and after arrival in 693 (89.9%) persons. Clinical malaria occurred <30 days after arrival in 398 (80.1%) of the 497 of persons with P. falciparum infections and in 74 (35.9%) of the 206 persons with P. vivax infections (Table 5). Six (0.8%) of the 771 persons became ill with a P. vivax infection >1 year after returning to the United States. Imported Malaria Among U.S. Military PersonnelIn 2007, a total of 33 cases of imported malaria were reported among U.S. military personnel. Nineteen persons reported travel to Afghanistan, and 10 reported travel to South Korea; the remaining four persons reported travel to Iraq and two unspecified countries in Africa. Information on infecting species was known for 25 cases; all cases were P. vivax. Of these 25 cases, 15 were among persons who reported having taken the appropriate primary chemoprophylactic drug; four reported taking the recommended primaquine for presumptive antirelapse therapy, and five patients reported adherence to the prescribed drug regimen. These cases were reported by state health departments and do not include all cases reported through malaria surveillance activities conducted by the U.S. Department of Defense. Prophylaxis Use Among U.S. CiviliansInformation concerning chemoprophylaxis use and travel area was known for 646 (92.2%) of the 701 U.S. civilians who had imported malaria. Of these 646 persons, 205 (31.7%) had taken chemoprophylaxis. Of the 205 persons who reported taking malaria chemoprophylaxis, 53 (25.9%) had not taken a CDC-recommended drug for the area visited, and 143 (69.8%) had taken a CDC-recommended medication. Data for the specific drug taken was missing for the remaining nine (4.4%) travelers. A total of 66 (46.2%) patients taking CDC-recommended chemoprophylaxis reported having taken mefloquine, 42 (29.4%) doxycycline, and 27 (18.9%) atovaquone/proguanil; four patients (2.8%) who had traveled only in areas where chloroquine-resistant malaria has not been documented reported having taken chloroquine. Four patients took a combination of two CDC-recommended malaria prophylactics for the specific travel region. Malaria Infection After Recommended Prophylaxis UseA total of 143 U.S. civilians contracted malaria after taking a recommended antimalarial drug for chemoprophylaxis. Of these, 43 (30.1%) reported complete adherence with the drug regimen, and 85 (59.4%) reported nonadherence; adherence was unknown for the remaining 15 (10.5%). Information regarding infecting species was available for 113 (79%) patients who had taken a recommended antimalarial drug and undetermined for the remaining 30 patients. Cases Caused by P. vivax or P. ovaleOf the 143 patients who had malaria diagnosed after recommended chemoprophylaxis use, 39 (27.3%) had cases that were caused by P. vivax, and 12 (8.4%) had cases caused by P. ovale. Of the 51 total cases of P. vivax or P. ovale, 42 (82.3%) occurred >45 days after arrival in the United States. These cases were consistent with relapsing infections and do not indicate primary prophylaxis failures. Information on four cases was insufficient to assess a relapse infection because of missing data regarding symptom onset or return date. A total of five cases occurred <45 days after the patient returned to the United States; all were caused by P. vivax. Four of the five patients did not adhere to their malaria chemoprophylaxis regimen. The patient who contracted malaria but reported adherence to the chemoprophylaxis regimen had traveled to Papua New Guinea and had taken atovaquone/proguanil for malaria chemoprophylaxis. Possible explanations for this case include inappropriate dosing, unreported nonadherence, malabsorption of the drug, an early relapse from hypnozoites established at the start of this trip, or emerging parasite resistance. Cases Caused by P. falciparum or P. malariaeSixty of the 143 patients who had malaria diagnosed after recommended chemoprophylaxis use included 48 cases of P. falciparum and 12 of P. malariae. Of the 48 P. falciparum cases, all except two cases were acquired in Africa; one was acquired in Vietnam and one in India. Forty-two (87.5%) patients reported nonadherence to the antimalarial drug regimen, and three persons had no adherence information available. Three (6.3%) patients who had all contracted malaria and had traveled to Africa reported adherence with antimalarial chemoprophylaxis; one patient took doxycycline, one patient took atovaquone/proguanil, and one took mefloquine. Of the 12 P. malariae cases, 10 were acquired in Africa, and one was acquired in Asia (Indonesia). Six of the patients reported nonadherence to the antimalarial drug regimen, and two had no adherence information available. The remaining four patients reported drug regimen adherence; two took mefloquine, and two took atovaquone-proguanil Cases of Mixed Species InfectionOf the 143 patients who had taken a recommended malaria chemoprophylaxis, two reported a mixed Plasmodium species infection. One patient who traveled to Nigeria acquired a mixed infection of P. falciparum and P. ovale, and one patient who traveled to Indonesia acquired a mixed infection of P. falciparum and P. vivax. Both patients reported taking mefloquine for malaria chemoprophylaxis; however, neither patient adhered completely to the drug regimen. Clinical ComplicationsClinical complications associated with malaria were reported for 358 (23.8%) of the total 1,505 reported cases. One case was fatal. Although patients can have multiple clinical complications associated with malaria, the largest proportion (53.4%) of patients experienced anemia (hemoglobin <11 g/dL or hematocrit <33%). Of the 358 cases with clinical complications, 57 (15.9%) cases were classified as severe malaria, because one or more of the following manifestations were reported: cerebral malaria, renal failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), jaundice, or >5% parasitemia. Severe anemia (hemoglobin <7 g/dL) is also a characteristic of severe malaria (12); however, because data for severe anemia are not collected on the surveillance form, the percentage of severe malaria cases might have been higher.† Of the 57 patients with severe malaria, four (7%) reported taking chemoprophylaxis; however, none reported complete adherence to the drug regimen. Of the 57 patients with severe malaria cases, seven were treated using an investigational new drug protocol for intravenous artesunate; all seven patients recovered after treatment. Purpose of TravelPurpose of travel to areas where malaria is endemic was reported for 599 (85.4%) of the 701 U.S. civilians with imported malaria. Though travelers could report multiple reasons for travel, the largest proportion (62.8%) was persons who had visited friends or relatives in malarious areas; the second and third highest proportions (10.2% and 8.5%) were persons who had traveled as tourists or missionaries, respectively (Table 6). Proportions of various reasons for travel remained stable during 2005--2007. Malaria by AgeAmong the 1,464 cases among patients for whom age was known, 295 (20.2%) cases occurred in persons aged <18 years, 1,115 (76.2%) in persons aged 18--64 years, and 54 (4.6%) in persons aged >65 years. Although the majority of cases occur in persons aged 18--64 years, pediatric cases are of particular interest because the preventive care of most children is controlled by parents or guardians. Of the 295 (20.2%) cases among persons aged <18 years, 100 (33.9%) cases occurred among U.S. civilian children, 105 (35.6%) cases among children of foreign citizenship, and for 90 (30.5%) children, resident status was unknown. Seventy-one (71.0%) of the cases among U.S. civilian children for whom country of exposure was known were attributable to travel to Africa. Of the 100 cases among U.S. civilian children, two (2.0%) children were aged <24 months, 22 (22.0%) were aged 24--59 months, 41 (41.0%) were aged 5--12 years, and 35 (35.0%) were aged 13--17 years. Of the 87 children for whom reason for travel was known, 73 (83.9%) were reported as visiting friends and relatives; the remaining 14 cases were attributed to tourist, missionary, and student travel. Thirty-one (33.3%) of the 93 children for whom chemoprophylaxis information was known were reported as having taken chemoprophylaxis, of whom 28 (90.3%) had taken an appropriate regimen; however, eight (28.6%) reported complete adherence. Malaria During PregnancyA total of 24 cases of malaria were reported among pregnant women in 2007, representing 4.5% of cases among all women. Fourteen (58.3%) of the 24 cases occurred among U.S. civilian pregnant women; 21 of these patients reported travel to Africa, and three reported travel to Central and South American countries. Thirteen women reported visiting friends and relatives, and one reported missionary-related travel. Of the 14 cases of malaria reported among U.S. civilian pregnant women, three (21.4%) women reported taking malaria chemoprophylaxis. One woman reported taking an appropriate medication; however, she did not complete the drug regimen. No information was available on the birth outcomes of these women. Selected Malaria Case ReportsMalaria Associated with Blood Transfusion One case of induced malaria, caused by blood transfusion in the United States, was reported in 2007. A black woman aged 25 years with transfusion-dependent sickle cell disease and no previous travel history was admitted to a Houston, Texas, hospital on August 12, 2007, with complaints of abdominal pain. Treatment was provided for sickle cell crisis. On August 16, 2007, the woman became febrile and was evaluated for causes of fever. On August 20, 2007, P. falciparum malaria with 16% parasitemia was diagnosed, and quinidine and doxycycline were administered. A retrospective review of blood samples obtained on hospital admission revealed that the woman was parasitemic on the date of admission. The patient tolerated quinidine well and by August 24, 2007, her physician reported resolution of parasitemia. However, on August 28, 2007, the patient, who was still hospitalized, developed ARDS and acute renal failure, requiring mechanical ventilation and hemodialysis. After prolonged hospitalization, she recovered and was discharged. During the year before admission, the woman had 66 units of red blood cells transfused; her most recent transfusions had occurred on June 12, 2007, and July 18, 2007. All of the units that she had received during June 12--July 18 had come from the same blood distribution facility. The hospital's transfusion services department was contacted to initiate an investigation of the donors of the units and identify the infected donor, thus preventing additional transfusion-related infections. Serologic testing using indirect immunofluoresence antibody identified one donor with elevated titers of antibodies to malaria consistent with previous malaria infection at an indeterminate time. All other donors' serologic tests were negative. The implicated donor was located and questioned regarding malaria history. The donor reported immigrating to the United States from Nigeria in 2001 and indicated that he had not traveled abroad since that time. The donor reported that in 1988, he was hospitalized for a severe febrile illness that was presumed to be a malaria infection. He did not recall the infecting species or the treatment provided. Investigators explained to the donor that his donated blood was likely to be the source of a malaria infection in another patient. He understood the findings but chose not to undergo any type of malaria therapy because he did not feel ill; however, he understood that he should be alert for any future episodes. The implicated donor was counseled not to donate blood until 3 years after undergoing an appropriate malaria therapy. Imported Malaria Possibly Associated with Organ TransplantationOn January 18, 2007, a man aged 53 years returned to California after a 3-week trip to Pakistan for a kidney transplant; he did not take malaria chemoprophylaxis before his trip. During his stay in Pakistan, the man reported spending most of his time indoors. The transplant surgery was performed on January 7, 2007; the transplanted kidney came from India. During the transplant surgery, no transfusions were administered. On January 25, 2007, the man developed a fever and sought medical attention. Infection with P. vivax was diagnosed. Although the patient might have acquired the infection naturally in Pakistan, the kidney transplant procedure might have been the source. Death Attributed to MalariaOne death attributable to malaria was reported in 2007. A man aged 67 years from India was visiting the United States to attend a wedding. He had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia. On October 17, 2007, the man was admitted to a U.S. hospital with fever, and P. vivax malaria infection was diagnosed. He was treated with quinine sulfate and doxycycline and subsequently had a negative blood smear. However, the man then developed respiratory failure and ARDS, which eventually resulted in severe hypoxia. The man developed oliguric renal failure and multisystem organ failure. He died on November 21, 2007. DiscussionA total of 1,505 cases of malaria were reported to CDC for 2007, which is not significantly different from the number of cases reported in 2006. The number of cases reported with no information regarding residence status or clinical findings decreased from 634 in 2006 to 508 in 2007 (9). Excluding cases with no information on residence status, the percentage of U.S. resident cases during 2000--2007 remained stable. During 2002--2007, the proportion of cases from Asia increased. The number of cases acquired in a specific region can be affected by many factors, including the amount of transmission occurring in the region, adherence to preventive measures (including mosquito avoidance and chemoprophylaxis) by travelers, the style of travel that occurs in that country (e.g., business or adventure travel), and the volume of travel to those countries. Of the 1,504 imported cases, 508 (33.8%) cases did not have information on residential status. In addition, 350 (23.3%) cases did not have information describing travel history. High numbers of cases with no reported residential and clinical information compromises the ability of the data to accurately reflect trends in malaria surveillance in the United States. Continued vigilance is needed by local and state health departments, health-care providers, and other health personnel in providing essential information regarding malaria cases when submitting cases through the various reporting systems to CDC. Malaria cases acquired in Africa continue to account for the largest number of U.S. cases acquired from a specific region. The West African region accounts for almost 74% of the cases acquired in the continent; however, the number of cases acquired in Tanzania and Burundi increased. In 2006, only eight cases were acquired from Tanzania, and no persons with a malaria infection reported travel to or from Burundi (9). In 2007, a combined total of 61 cases were acquired in either Tanzania or Burundi. Among these, 57 persons were identified as resettling refugees or immigrants as their reason for travel to the United States. CDC recommends presumptive treatment of P. falciparum malaria in refugees who are from areas where malaria is endemic before entering the United States to resettle. To ensure adequate presumptive treatment, the treatment regimen must be completed no sooner than 3 days before departure to the United States (13). This strategy decreases risk for symptoms, severe complications, or death associated with a malaria infection that could occur after arriving in the United States. Because refugees might settle in areas where access to health care is difficult to obtain or health-care providers are not familiar with malaria diagnosis or treatment, treating possible malaria infections in refugees before they immigrate to the United States is optimal to prevent ongoing infections from progressing to severe disease after arrival in the United States. Presumptive treatment also can reduce the risk for malaria reintroduction in the United States because the malaria vector, the female Anopheles mosquito, is found throughout the continental United States. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) is an intergovernmental agency that evaluates most refugees bound for the United States and provides treatment for certain infectious diseases. To reduce the incidence of malaria among refugees after they arrive in the United States, IOM administered presumptive malaria treatment against P. falciparum to Burundi refugees resettling from Tanzania. In 2005, CDC recommended artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) as presumptive P. falciparum treatment for refugees resettling to the United States from sub-Saharan Africa (14). However, until July 2007, IOM continued to implement sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) treatment for malaria to refugees before arrival in the United States; P. falciparum infections in sub-Saharan Africa have considerable resistance to SP (15). Therefore, SP resistance is a possible explanation for the increase of cases in Burundi refugees who immigrated to the United States in 2007. In response to such cases, IOM is now implementing ACT treatment as presumptive P. falciparum treatment for refugees resettling in the United States (14). A total of 7,545 Burundian refugees from Tanzania resettled to the United States during 2007--2008 (16). Health-care providers in the United States caring for refugees resettling from malaria-endemic regions should remain aware of the possibility of malaria in this population, regardless of previous treatment. One reason malaria surveillance is conducted is to monitor for prophylaxis failures that might indicate emergence of drug resistance. However, approximately 82% of imported malaria cases among U.S. residents for whom prophylaxis use was known occurred among persons who were not taking prophylaxis, were taking prophylaxis but not the regimen recommended for the region to which they were traveling, or were taking a recommended prophylactic regimen incorrectly. The majority of patients for whom appropriate prophylaxis was reported and who did not have a relapsing infection reported nonadherence with the recommended regimen or provided insufficient information to determine whether they adhered to an appropriate antimalarial chemoprophylaxis regimen. In the small subset of patients who reported choosing and adhering to the recommended prophylactic drug regimen, subsequent malaria might have been a result of malabsorption of the antimalarial drug or emerging drug resistance. Because CDC does not routinely evaluate blood drug levels among patients with malaria who report adherence with a recommended regimen, determining whether adherence reporting is inaccurate, the antimalarial drug was malabsorbed, or the patient was experiencing emerging drug resistance is not possible. No conclusive evidence exists to indicate a single national or regional source of infection among this group of patients or the failure of a particular chemoprophylactic regimen. Health-care providers who suspect chemoprophylaxis failure should contact CDC quickly, which will enable CDC to measure patient antimalarial blood drug levels and assess the parasite in vitro for genetic resistance characteristics to evaluate for possible drug resistance. Severe malaria is characterized by one or more of the following clinical complications: prostration, impaired consciousness or coma, respiratory distress, seizures, shock, ARDS, jaundice, severe anemia, acute renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, acidosis, hemoglobinuria, and >5% parasitemia (17). Intravenous quinidine gluconate, principally used as an antiarrhythmic medicine, also has antimalarial properties and is the only parenteral drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of severe malaria that is available in the United States. However, quinidine has cardiotoxic effects and has become less available in U.S. hospitals with the advent of newer antiarrhythmic drugs (18,19). Since 2000, the World Health Organization has recommended artemisinins such as artesunate rather than quinidine for treatment of severe malaria; artesunate has been used outside the United States for many years (17). On June 21, 2007, CDC's investigational new drug (IND) protocol for intravenous artesunate became effective, allowing the use of intravenous artesunate for the treatment of severe malaria. The medication is stocked at eight quarantine stations around the United States and can be shipped quickly when needed. Precise guidelines must be followed and eligibility requirements must be met to enroll a patient in the treatment protocol. Artesunate is provided free of charge to hospitals on request and on an emergency basis by the CDC Drug Service or by one of the CDC quarantine stations. Physicians who administer the drug to patients must notify CDC of any resulting adverse effects and comply with the IND protocol (20). To enroll a patient with severe malaria in this treatment protocol, health-care providers should call CDC's Malaria Hotline (Table 7). As in previous years, the majority of malaria cases in 2007 were among persons who traveled to visit friends and relatives. Foreign-born U.S. civilians need to be aware that acquired immunity wanes quickly when exposure to malaria is interrupted and that they should take prophylaxis when returning to malarious areas. In addition, children of foreign-born U.S. civilians who are born in the United States have no immunity to malaria and are vulnerable to infection (21). In this report, approximately three fourths of the children who were visiting friends and relatives and contracted malaria had not been taking any chemoprophylaxis or had been taking an incorrect medication for chemoprophylaxis. Twenty-four cases were reported in pregnant women, which is a 41% increase from 2006. Among the 14 U.S. civilian women who were pregnant and contracted malaria, three (21.4%) women reported taking chemoprophylaxis, and none of these three completely adhered to the drug regimen. The proportion of pregnant women taking chemoprophylaxis is lower than the percentage of total U.S. civilians with malaria who took chemoprophylaxis. Malaria during pregnancy poses a high risk for both maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality (22). Pregnant women should be counseled to avoid travel to malarious areas. If deferral of travel is impossible, pregnant women should be informed that the risks for malaria greatly outweigh those associated with prophylaxis, and chemoprophylaxis should be used. Information for pregnant women is available at http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/travel/drugs_pregnant_public.htm. Appropriate chemoprophylaxis, promptly seeking medical care if symptoms develop, and consideration of malaria in the differential diagnosis of fever in a traveler who has returned to the United States will help ensure malaria is properly managed and controlled in the United States. In addition, because induced malaria infections are possible, health professionals and blood donation and collection staff members must be attentive and thorough in their blood deferment protocols. FDA screening guidelines indicate that residents of countries where malaria is not endemic who then travel to areas where malaria is endemic should not be accepted as blood donors until 1 year after their departure from the malarious area. Former residents of areas where malaria is endemic should be deferred from blood donation until 3 years after their departure from the malarious area. Persons who receive a diagnosis of malaria should not donate blood until 3 years after treatment, during which time they must have remained asymptomatic (23). Signs and symptoms of malaria are often nonspecific, but fever usually is present. Other symptoms include headache, chills, increased sweating, back pain, myalgia, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and cough. Prompt diagnosis requires that malaria be included in the differential diagnosis of illness in a febrile person with a history of travel to a malarious area. Clinicians should ask all febrile patients for a travel history, including international visitors, immigrants, refugees, migrant laborers, and other international travelers. Prompt treatment of suspected malaria is essential because persons with P. falciparum infection are at risk for experiencing life-threatening complications soon after onset of illness. Ideally, therapy for malaria should be initiated immediately after the diagnosis has been made. Treatment should be determined on the basis of the infecting Plasmodium species, the probable geographic origin of the parasite, the parasite density, and the patient's clinical status (22). If a diagnosis of malaria is suspected and cannot be confirmed, or if a diagnosis of malaria is confirmed but species determination is not possible, antimalarial treatment should be initiated that is effective against P. falciparum. Resistance of P. falciparum to chloroquine is worldwide, with the exception of a limited number of geographic regions (e.g., Mexico and Central America); therefore, therapy for presumed P. falciparum malaria should include a drug effective against such resistant strains (24). Health-care providers should be familiar with prevention, recognition, and treatment of malaria and are encouraged to consult appropriate sources for malaria prevention and treatment recommendations (Table 7). Physicians seeking assistance with the diagnosis or treatment of patients with suspected or confirmed malaria should call CDC's Malaria Hotline (Table 7) during regular business hours; during evenings, weekends, and holidays, physicians should call CDC's Emergency Operations Center (Table 7) and ask the staff member to page the person on call for the Malaria Branch. These resources are intended for use by health-care providers only. Detailed recommendations for preventing malaria are available to the general public online at http://www.cdc.gov/travel/diseases.htm/malaria. In addition, CDC biannually publishes recommendations in Health Information for International Travel (commonly referred to as The Yellow Book) (1), which is available for purchase from Elsevier (http://www.elsevierhealth.com or telephone: 800-545-2522); the publication is also available and updated more frequently on the CDC Travelers' Health site at http://wwwn.cdc.gov/travel. Additional information on malaria prevention recommendations is available through the online CDC malaria map application (http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/risk_map). The application is an interactive map that provides information on malaria risk throughout the world. Users can search for or browse through countries, cities, and place names and obtain information about malaria and recommended malaria prevention medications in particular locations. The malaria map application complements resources currently available on the CDC Travelers' Health website. CDC provides assistance for diagnostic parasitology through DPDx, CDC's Division of Parasitic Diseases diagnostic website. DPDx (available at http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx) provides free Internet-based laboratory diagnostic assistance (i.e., telediagnosis) to laboratorians and pathologists who are investigating suspected parasitic disease cases, such as malaria. Digital images captured from diagnostic specimens can be submitted by e-mail for consultation. Telediagnosis assistance from CDC is available during regular business hours (Monday--Friday, 8 a.m.--4:30 p.m. EST). Because laboratories can transmit images to CDC and obtain a rapid response (average time: minutes to several hours) to their inquiries, DPDx allows efficient diagnosis of challenging cases and rapid dissemination of information. As of January 2007, approximately 49 public health laboratories in 46 states and Puerto Rico had the ability to perform telediagnosis. Implementation of telediagnosis at public health laboratories is supported by CDC, including training of personnel in digital imaging techniques and diagnostic identification of parasites. The DPDx Internet site is CDC's reference for the telediagnosis of parasitic diseases and also serves as an online guide for diagnostic parasitology. The DPDx website contains reference material with images, text, and videos on approximately 100 different species of parasites, covering information on laboratory diagnosis, geographic distribution, clinical features, treatment, and life cycles. Acknowledgments The authors acknowledge the state, territorial, and local health departments; health-care providers; and laboratories for reporting this information to CDC. References

* To confirm malaria diagnosed by blood films from questionable cases and to obtain appropriate treatment recommendations, contact either the state or local health department or CDC's Malaria Hotline (telephone: 770-488-7788).

† Data on severe anemia (hemoglobin <7 mg/dL) will be reported in subsequent malaria surveillance summaries. Table 1  Return to top. Figure 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top. Figure 2  Return to top. Table 3

Return to top. Table 4  Return to top. Table 5  Return to top. Table 6  Return to top. Table 7  Return to top.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Date last reviewed: 4/2/2009 |

|||||||||

|