|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Law and Public Health at CDCRichard A. Goodman, MD, JD,1 A. Moulton,

PhD,1 G. Matthews, JD,2 F. Shaw, MD,

JD,1 P. Kocher, JD,3 G. Mensah,

MD,4 S. Zaza, MD,5 R. Besser,

MD5

Corresponding author: Richard A. Goodman, MD, JD, Public Health Law Program, CDC, MS D-30, Atlanta, GA 30333. Telephone: 404-639-4625; Fax: 404-639-7121; E-mail: [email protected].

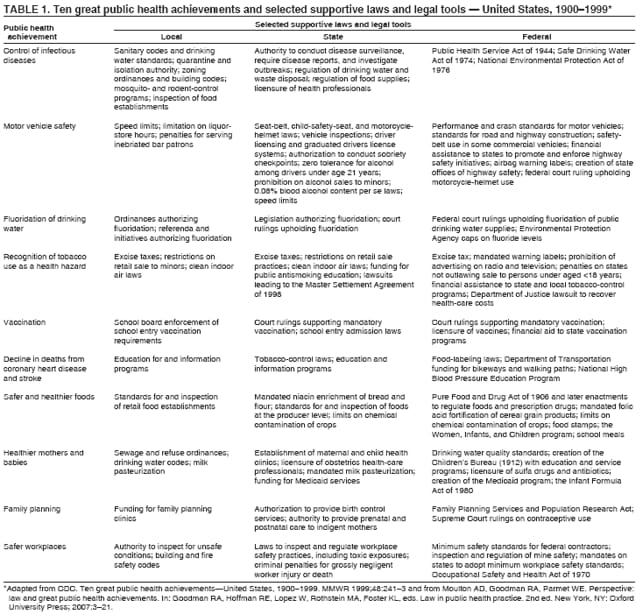

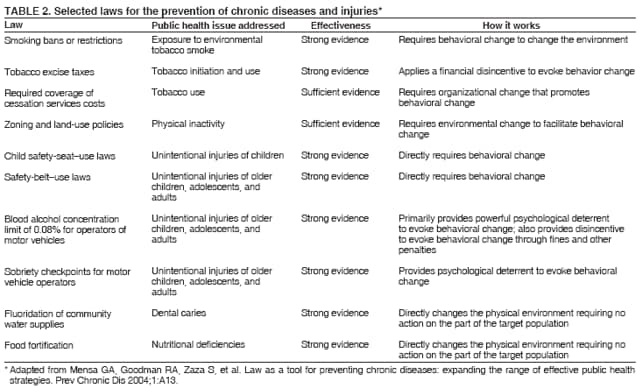

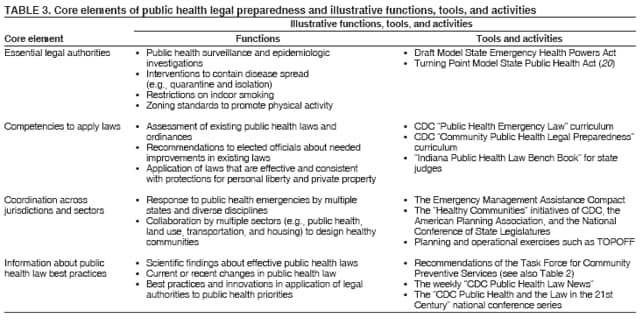

Health officers must be familiar not only with the extent of their powers and duties, but also with the limitations imposed upon them by law. With such knowledge available and widely applied by health authorities, public health will not remain static, but will progress. ---James A. Tobey, 1947 (1) IntroductionPublic health law is an emerging field in U.S. public health practice. The 20th century proved the indispensability of law to public health, as demonstrated by the contribution of law to each of the century's 10 great public health achievements (Table 1) (2,3). Former CDC Director Dr. William Foege has suggested that law, along with epidemiology, is an essential tool in public health practice (4). Public health laws are any laws that have important consequences for the health of defined populations. They derive from federal and state constitutions; statutes, and other legislative enactments; agency rules and regulations; judicial rulings and case law; and policies of public bodies. Government agencies that apply public health laws include agencies officially designated as "public health agencies," as well as health-care, environmental protection, education, and law enforcement agencies, among others. Scope of Public Health LawLaw is foundational to U.S. public health practice. Laws establish and delineate the missions of public health agencies, authorize and delimit public health functions, and appropriate essential funds. The concept of public health law gained momentum early in the 20th century in James Tobey's seminal volumes (1). Frank Grad's practical guide, The Public Health Law Manual (5), and Lawrence Gostin's treatment of public health law under the U.S. constitutional design followed (6). A CDC-related contribution to this literature emphasized the interdisciplinary relation between law and public health practice (7). The concept of public health law has evolved into overlapping paradigms. One paradigm frames public health practice in relation to multiple sources of law (e.g., statutes and regulations) and to fields of law (e.g., constitutional and environmental law). The other, a more scholarly view, focuses on the legal powers and duties of government to ensure public health and limitations on government powers to constrain the protected liberties of individuals. Integration of Public Health Law Within CDC and State Public Health PracticePublic health law at CDC and at many of its partner organizations has earned explicit recognition only recently. During CDC-sponsored workshops on public health law in 1999--2000, major public health stakeholders, including health officers, epidemiologists, public health lawyers, educators, and legislators, called for strengthening the legal foundation for public health practice. These stakeholders concluded that public health would benefit by adding legal skills and scientific knowledge about the impact of law on public health to the toolkits of public health practitioners. CDC consequently established its Public Health Law Program (PHLP) in 2000 with a mission for improving the public's health through law (8). Primary goals of PHLP are to enhance the public health system's legal preparedness to address emerging threats, chronic diseases, and other national public health priorities and to improve use of law to support program activities. PHLP focuses on these goals by 1) strengthening the competencies of public health professionals, attorneys, and other practitioners to apply law to public health; 2) stimulating applied research about the effectiveness of laws in public health; 3) fostering partnerships among organizations and professionals working in public health and law; and 4) developing and disseminating authoritative information about public health law to public health practice, policy, and other communities (8). PHLP does not provide legal advice to CDC programs; that remains the separate responsibility of the Office of the General Counsel of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. State and local partners also are strengthening public health legal preparedness. CDC has stimulated this in part through initiatives such as "Public Health Emergency Law," a course delivered nationally in state and local health departments (8). In some states, grassroots activities are increasing competencies of practitioners to use law and strengthening legal preparedness capacities of public health systems. For example, in California, the Public Health Law Work Group (comprising representatives of county counsel and city attorney offices) drafted a legally annotated health officer practice guide for communicable disease control (9). Related activities in California include a 2006 conference on legal preparedness for pandemic influenza, and a series of forensic epidemiology joint training programs for public health and law enforcement agencies. Role of Public Health Law in Addressing High Priorities in Public HealthThe indispensable role of law is evident across the entire history of U.S. public health---from early colonialists' needs to defend against infectious threats to today's innovative law-based approaches to preventing chronic diseases, injuries, and other problems (Table 2). The U.S. experience with smallpox illustrates how, at some points in history, law-based interventions were implemented even before science elucidated the nature of the public health threat and the basis of the intervention. The legal-epidemiologic strategy of quarantine to prevent the spread of smallpox was employed on Long Island as early as 1662 (10). Smallpox prevention also was at the root of the 1905 landmark decision in Jacobson v. Massachusetts in which the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Massachusetts statutory requirement for smallpox vaccination (11). Public health is examining law-based countermeasures to the use of smallpox virus and other infectious pathogens as biologic weapons. In its program of grants supporting states' development of capacity to address public health emergencies, CDC expects states to attain legal preparedness for such emergencies in the wake of the 2001 anthrax attacks, the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic in 2003, the 2005 hurricane disasters, and the specter of an A(H5N1) influenza pandemic. Response to these threats has spawned new and innovative resources, such as the draft Model State Emergency Health Powers Act, the CDC forensic epidemiology course for joint training of public health and law enforcement officials, community public health legal preparedness workshops for hospital and public health attorneys, public health law "bench books" for the judiciary, and the CDC Public Health Emergency Legal Preparedness Clearinghouse (8). Public health law also helps address high priorities other than infectious diseases and emergencies, as illustrated by the roles of law and legal strategies in tobacco control (12). CDC and others are exploring the role of law in preventing chronic diseases (13), including development of legal frameworks for addressing cardiovascular disease (14) and obesity (15), and for fostering healthy built environments (16). Injury prevention has benefited from litigation, laws requiring preventive measures, and other legal interventions (17,18). In 2002, a rich multidisciplinary public health law community began taking shape at the first national public health law conference, which CDC convened. This community comprises practitioners trained in the classical disciplines of public health, attorneys in the public and private sectors, increasing numbers of professionals trained and experienced in both public health and law, elected officials, emergency management and law enforcement professionals, judges, educators, researchers, and others. The more than 7,000 current subscribers to the weekly CDC Public Health Law News (8) attest to the size of the community. Requirements for Achieving Full Public Health Legal Preparedness to Support the Mission of Public HealthEffective responses to emerging threats and attainment of public health goals require CDC, partner organizations, and communities to achieve full public health legal preparedness (13,19). Public health legal preparedness, a subset of public health preparedness, is the attainment by a public health system of specified legal benchmarks or standards essential to preparedness of the public health system (19). The elements of public health legal preparedness (Table 3) include requirements to

CDC increasingly envisions public health law as an integral element in the armamentarium of each of its programs and in the competencies of its professionals. CDC and its partners are working vigorously toward full legal preparedness throughout the public health system, developing and deploying new legal tools that policymakers and front-line practitioners will apply to the entire spectrum of 21st-century public health challenges and opportunities. References

Table 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top. Table 3  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Date last reviewed: 12/18/2006 |

|||||||||

|