Key points

This chapter provides general guidance for vaccine-preventable disease surveillance, describing the disease background/epidemiology, case investigation and reporting/notification, disease case definitions, and activities for enhancing surveillance, case investigation, and outbreak control for tetanus.

Disease Description

Tetanus is an acute, potentially fatal disease characterized by generalized rigidity and convulsive spasms of skeletal muscles. Tetanus is caused by the spore-forming bacterium Clostridium tetani. Spores of C. tetani (the dormant form of the organism) are found in soil contaminated with animal and human feces. The spores enter the body through breaks in the skin and germinate under anaerobic conditions. Puncture wounds and wounds with significant tissue injury are more likely to promote germination. The organisms produce a potent toxin, tetanospasmin, which binds to gangliosides at the neuromuscular junction and proceeds along the neuron to the ventral horns of the spinal cord or motor horns of the cranial nerves in 2–14 days. The toxin can also be absorbed into the bloodstream and lymphatics. Once the toxin reaches the nervous system, it causes painful and often violent muscular contractions. The muscle stiffness usually initially involves the jaw (lockjaw) and neck and later becomes generalized. Tetanus is a noncommunicable disease—it is not transmitted from one person to another.

Background

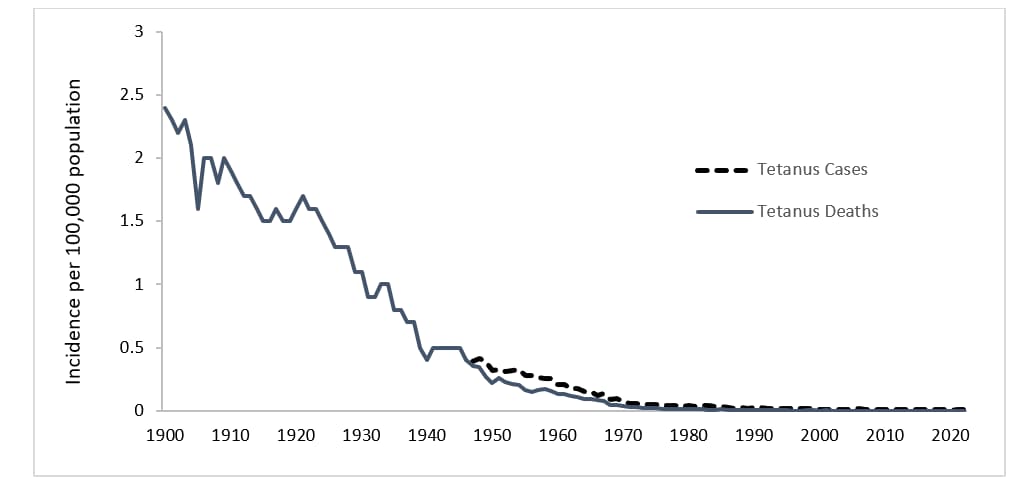

Figure 1. Mortality and incidence rates of tetanus reported in the United States, 1900–2022.

In the United States, reported mortality due to tetanus has declined >99% since the early 1900s and has remained relatively constant since 2000, averaging about two deaths per year. Documented tetanus incidence has declined by approximately 99% since 1947, when national reporting of tetanus cases began (Figure 1). Several factors have contributed to the decline in tetanus morbidity and mortality, including the widespread use of tetanus toxoid–containing vaccines since the late 1940s1. A combined diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine was first recommended in 19482. Next, the use of tetanus immune globulin (TIG), either for prophylaxis in wound management or for treatment of tetanus, has prevented cases and reduced the severity of tetanus cases. TIG first became available from equine sources during World War I in the 1910s, and then, human-derived TIG became available in the 1960s1. In addition, improved wound care, adoption of aseptic surgical techniques, and hygienic childbirth and wound care practices contributed to the decline in cases. Further, increased rural-to-urban migration with consequent decreased exposure to tetanus spores may also have contributed to the decline in tetanus mortality noted during the first half of the 20th century1.

From 2013 through 2022, a total of 267 cases and 13 deaths from tetanus were reported in the United States through the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS)3. The effectiveness of tetanus toxoid-containing vaccines is very high, although not 100%4. Vaccination status was known for 67 (25%) tetanus cases reported from 2013 to 20223. Only 16 (24%) were reported to have received three or more doses of tetanus toxoid-containing vaccines. The remaining patients were either unvaccinated or had received fewer than three doses of tetanus toxoid.

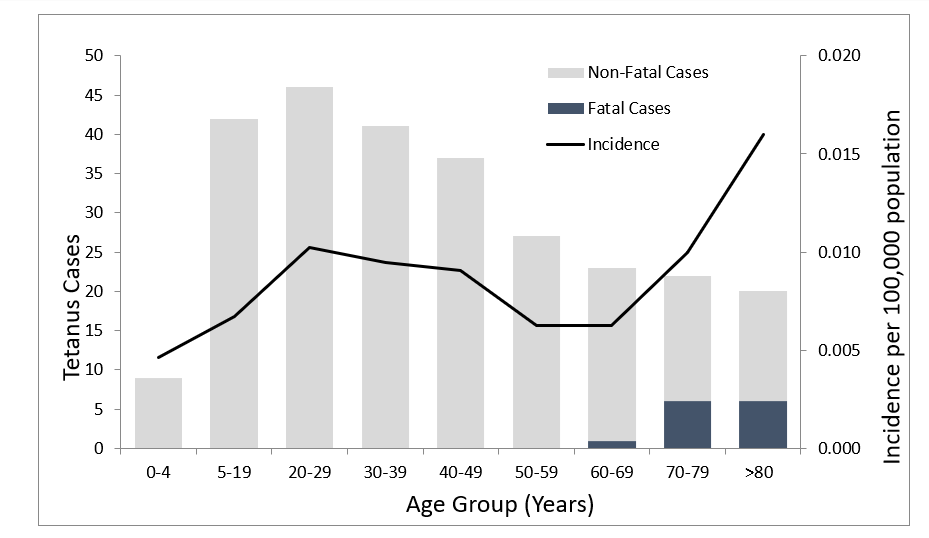

Figure 2. Number of reported cases of tetanus, survival status of patients, and average annual incidence rates by age group—United States, 2013–2022

Of the 267 cases of tetanus, 54 (20%) were in people 65 years of age or older, 162 (61%) were in people 20 through 64 years of age, and 51 (19%) were in people younger than 20 years, including 1 case of neonatal tetanus (Figure 2). All tetanus-related deaths occurred among patients >60 years of age3.

During 2013 through 2022, coverage at age 24 months with at least three doses of DTaP was 92% or higher56. Coverage of an adolescent Tdap or Td dose was consistently above 89%7. For adults, in 2022, coverage with at least one dose of Td or Tdap was 66% for those aged 18–64 years compared to 60% for those 65 years of age and older8. A national population-based seroprevalence survey conducted from 2015–2016 found that 94% of people aged six years and older had protection against tetanus9. This was higher than previous estimates from 1988–1994, which found only 72% protection in the same population10. This lower percent coverage in the older survey compared to more recent findings likely reflects that adults aged 50 years and older in the prior study were born before childhood vaccination with a primary series of tetanus-containing vaccines was widely recommended9. In the 2015–2016 study, those ≥80 years, particularly women, had lower population-level protection (76%) against tetanus compared to younger ages. One possibility for the lower protective immunity in females in this age group is that this age group was born before the introduction of tetanus-containing vaccines into childhood vaccination, and men were more likely to serve in the military and thus were subject to mandatory vaccination.

Beyond age and lack of up-to-date tetanus vaccination status1112, diabetes, a history of immunosuppression, and intravenous drug use are risk factors for tetanus1314. From 2013 through 2022, people with diabetes accounted for 10% of all reported tetanus cases and 17% of all tetanus deaths. People who inject drugs accounted for 9% of cases from 2013 through 20223.

Despite the availability of highly effective tetanus-containing vaccines, tetanus continues to have a substantial health impact in the world, especially among under-vaccinated mothers and their infants following unhygienic deliveries15. Worldwide, reported neonatal tetanus cases decreased 89%, from 17,935 in 2000 to 1,995 in 2021; estimated neonatal tetanus deaths decreased 84%, from 46,898 to 7,71916. Despite this, disruptions to routine immunization programs during the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to an increase in neonatal tetanus cases since 2020 in 31% of countries prioritized for neonatal tetanus elimination. Globally, among all ages, there were an estimated 73,662 cases of tetanus in 2019, with the highest burden in eastern sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia17.

Importance of Rapid Case Identification

Tetanus is a clinical syndrome. Tetanus diagnosis is based solely on clinical presentation consistent with tetanus in the absence of an alternative or more likely cause. There are no tests that can confirm or rule out a tetanus diagnosis. CDC does not conduct or offer tetanus laboratory testing. Prompt clinical recognition of tetanus is important because hospitalization and treatment are required. Prompt treatment with TIG and other supportive care will decrease the severity of the disease. A single, 500 international unit (IU) dose of TIG for tetanus treatment is recommended for identified cases. TIG is available for commercial purchase in the United States. CDC does not stockpile or supply TIG.

Importance of Surveillance

Because tetanus is preventable, the possibility of failure to vaccinate or maintain up-to-date status with tetanus vaccination should be investigated in every case. Each case should be used as a case study to understand which measures, including prophylactic TIG, tetanus vaccination, and wound care, could have been taken to prevent such cases in the future.

Information obtained through surveillance is used to assess temporal, geographic, and demographic occurrence of tetanus. The data are also used to raise awareness of the importance of tetanus immunization and to characterize populations where additional efforts are needed to improve vaccination levels and prevention measures to reduce disease incidence.

Disease Reduction and Vaccine Coverage Goals

Because tetanus is a noncommunicable disease acquired from environmental exposure, herd immunity does not play a role in tetanus prevention. Therefore, vaccination is needed to provide individual protection. Healthy People 2030 aims to increase the uptake of 4 doses of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis-containing vaccine by age two years to 90%18. The most recent coverage estimate for ≥4 doses of DTaP for children born in 2020–2021 was 79.3%, a drop from 81.8% coverage from children born in 2018, likely due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic5. Moreover, Healthy People 2030 also aims to increase the proportion of adults 19 years of age or older who get recommended vaccines, including decennial Td or Tdap boosters for the prevention of diphtheria and tetanus19.

Case Definition

The following case definition for tetanus was approved by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) and published in 200920.

Clinical case definition

In the absence of a more likely diagnosis, an acute illness with muscle spasms or hypertonia and diagnosis of tetanus by a health care provider, or death, with tetanus listed on the death certificate as the cause of death or a significant condition contributing to death.

Case classification

Probable: A clinically compatible case, as reported by a healthcare professional.

There is no definition for confirmed tetanus.

Laboratory Testing

There is no laboratory test that diagnoses or rules out a tetanus diagnosis; the diagnosis is entirely clinical. C. tetani is recovered from wounds in only about 30% of cases, and the organism is sometimes isolated from patients who do not have tetanus. Serologic studies do not reliably evaluate individual-level tetanus immunity. Serologic results obtained before TIG is administered may support susceptibility if they demonstrate very low or undetectable anti-tetanus antibody levels but are not conclusive. However, tetanus can occur in the presence of "protective" levels of antitoxin (>0.1 IU by standard ELISA); therefore, serology cannot exclude the diagnosis of tetanus.

Reporting and Case Notification

Case reporting within a jurisdiction

Each state and territory (jurisdiction) has regulations or laws governing the reporting of diseases and conditions of public health importance21. These regulations and laws list the diseases to be reported and describe those people or groups responsible for reporting, such as healthcare providers, hospitals, laboratories, schools, daycare and childcare facilities, and other institutions. People reporting these conditions should contact their jurisdiction's health department for jurisdiction-specific reporting requirements. Detailed information on reportable conditions in each jurisdiction is available through CSTE22. Tetanus is a reportable disease in all states and territories of the United States. The Tetanus Surveillance Worksheet is included in Appendix 18 to guide data collection during the investigation of reported cases.

Case notification to CDC

Notifications for probable cases of tetanus should be sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) using event code 10210 in the NNDSS23. Reporting should not be delayed because of incomplete information. Data can be updated electronically as more information becomes available.

Information to collect

The case investigation should include collecting the epidemiologic information on the CDC Tetanus Surveillance Worksheet (Appendix 18). State health departments may supplement the suggested CDC investigation questions with additional information relevant to cases in their communities. The jurisdiction where the patient resides at diagnosis should submit the case notification to CDC.

As tetanus is a rare disease, all efforts should be made to complete the full epidemiologic information in Appendix 18 for each case. However, there is certain key information that should be completed for every reported tetanus case beyond the standard demographic data included for all reportable diseases:

- History: Tetanus vaccination history including years since last dose.

- Clinical Data: Whether an acute wound was identified and, if so, the principal wound type.

- Medical care before onset: Given tetanus toxoid vaccine, TIG, or had wound debrided before illness onset. Associated condition (if no acute injury) and whether there is a history of diabetes or parenteral drug abuse.

- Clinical course: Type of tetanus disease and whether illness resulted in death (may require follow-up over one month).

- Neonatal: Mother's age, mother's tetanus vaccination history, including years since the last dose, and child's birthplace.

Vaccination

For specific information about the use of tetanus vaccines, refer to The Pink Book, which provides general recommendations, including vaccine use and scheduling, immunization strategies for providers, vaccine content, adverse events and reactions, vaccine storage and handling, and contraindications and precautions.

Enhancing Surveillance

Several specific activities can improve the detection and reporting of tetanus cases and the comprehensiveness and quality of reporting. Additional activities are listed in Chapter 19, "Enhancing Surveillance."

Promoting awareness

Efforts should be made to promote awareness among clinicians to report suspected tetanus cases promptly. Lack of direct benefits, administrative burdens, and a lack of knowledge of reporting requirements all contribute to incomplete reporting of infectious diseases by physicians and other healthcare providers.

Providing feedback

National and statewide surveillance data concerning tetanus should be regularly shared with hospital epidemiologists, neurologists, and other clinicians; all should be regularly updated concerning reporting requirements. Feedback should also be provided to the people who report cases. Representatives from the jurisdiction and local health departments should attend scientific gatherings to share surveillance data and discuss the quality and usefulness of surveillance.

Review of mortality data

Mortality data are available through the vital records systems in all states, and they may be available soon after deaths occur in states using electronic death certificates. Although the number of tetanus cases in the United States is small, each is important and warrants a full investigation. Mortality data should be reviewed each year to identify deaths that may be due to tetanus. Any previously unreported cases identified through this review should be reported.

Streamlining reporting using electronic methods

The use of data from sources such as electronic medical records and electronic case reporting can significantly improve reporting speed, enhance data quality, and reduce workload24.

Case Investigation

The Tetanus Surveillance Worksheet (Appendix 18) [2 pages] may be used as a guideline for the investigation, with assistance from the jurisdiction's health department. Case investigations generally include reviews of hospital and clinic records and immunization registries, which are the best sources for information about diagnoses and immunization histories.

Authors and Suggested Citation

Michelle M. Hughes, PhD

Suggested citation:

Given the variations in the timing for when chapter updates are made, a Manual edition number is no longer used. Therefore, it is recommended that the date at the top right of the web page be used in references/citations.

Content source:

National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases

- Roper MH, et al. Tetanus Toxoid. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein A, Offit PA, Edwards KA, editors. (2018). Vaccines (7th ed.) Elsevier. p.1052–1079.e18.

- Miller JJ, Ryan ML. Immunization with combined diphtheria and tetanus toxoids (aluminum hydroxide adsorbed) containing H. pertussis vaccine: II. The duration of serologic immunity. Pediatrics 1948;1(1):8–22. https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/1/1/8/37830/IMMUNIZATION-WITH-COMBINED-DIPHTHERIA-AND-TETANUS

- CDC.National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, Weekly Tables of Infectious Disease Data. [cited 2024 August 23, 2024] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nndss/data-statistics/index.html

- Liang JL, Tiwari T, Moro P, Messonnier NE, Reingold A, Sawer M, et al. Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2018;67(2):1–44. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6702a1

- Hill HA, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, Mu Y, Chen M, Peacock G, et al. Decline in vaccination coverage by age 24 months and vaccination inequities among children born in 2020 and 2021—National Immunization Survey—Child, United States, 2021–2023. MMWR Morb and Mortal Wkly Rep 2024;73(38):844–53. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7338a3

- ChildVaxView: Vaccination coverage among young children (0–35 Months). [cited 2024 August 23, 2024] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/childvaxview/interactive-reports/index.html.

- TeenVaxView: Vaccination coverage among adolescents (13–17 Years). [cited 2024 August 23, 2024] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/teenvaxview/interactive/.

- AdultVaxView: Vaccination coverage among adults. [cited 2024 August 23, 2024] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/adultvaxview/about/general-population.html.

- Bampoe VD, Brown N, Deng L, Schiffer J, Jia LT, Epperson M. Serologic immunity to tetanus in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2015–2016. Clin Infect Dis 2024;78(2):470–5. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad598

- McQuillan GM, Kruszon-Moran D, Deforest A, Chu SY, Wharton M. Serologic immunity to diphtheria and tetanus in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2002;136(9):660–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-9-200205070-00008.

- Pierce C, Villamagna AH, Cieslak P, Liko J. Notes from the field: tetanus in an unvaccinated man from Mexico—Oregon, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72(24):665–6.

- Guzman-Cottrill JA, Lancioni C, Eriksson C, Yoon-Jae C, Liko J. Notes from the field: tetanus in an unvaccinated child — Oregon, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68(9):231–2.

- CDC. Tetanus among injecting-drug users—California, 1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1998;47(8):149–51.

- CDC.Tetanus surveillance — United States, 2001–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60(12):365–9.

- CDC. Global Tetanus Vaccination: Global Impact of Tetanus. [cited 2024 August 23, 2024] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/global-tetanus-vaccination/impact/index.html.

- Jones CE, Yusuf N, Ahmed B, Kassogue M, Wasley A, Kanu FA. Progress toward achieving and sustaining maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination— Worldwide, 2000–2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024;73(28):614–21. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7328a1

- Li J, Zicheng L, Chao Y, Kaiwen T, Sijie G, Shuang Z, et al., Global epidemiology and burden of tetanus from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Int J Infect Dis 2023;132:118–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2023.04.402

- Healthy People 2030: Increase the coverage level of 4 doses of the DTaP vaccine in children by age 2 years — IID-06. [cited 2024 August 23, 2024] Available from: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/vaccination/increase-coverage-level-4-doses-dtap-vaccine-children-age-2-years-iid-06.

- Healthy People 2030: Increase the proportion of adults age 19 years or older who get recommended vaccines — IID-D03. [cited 2024 August 23, 2024] Available from: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/vaccination/increase-proportion-adults-age-19-years-or-older-who-get-recommended-vaccines-iid-d03.

- CSTE.Public Health Reporting and National Notification for Tetanus. 2009. [cited 2024 August 23, 2024] Available from: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cste.org/resource/resmgr/PS/09-ID-63.pdf.

- Roush S, Birkhead G, Koo D, Cobb A, Fleming D. Mandatory reporting of diseases and conditions by health care professionals and laboratories. JAMA 1999;282(2):164–70. doi:10.1001/jama.282.2.164

- CSTE. State reportable conditions assessment. [cited 2024 August 26, 2024] Available from: https://www.cste.org/page/SRCA.

- CDC. Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS): Tetanus (Clostridium tetani) 2010 case definition. [cited 2024 August 23, 2024] Available from: https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/tetanus-2010/.

- Knicely K, et al. Electronic case reporting development, implementation, and expansion in the United States. Public Health Rep, 2024;139(4):432–42. doi: 10.1177/00333549241227160