|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

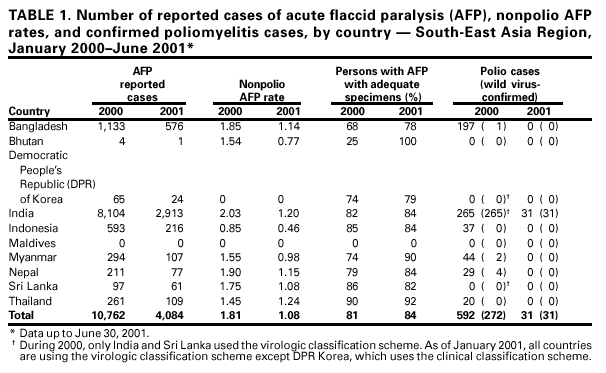

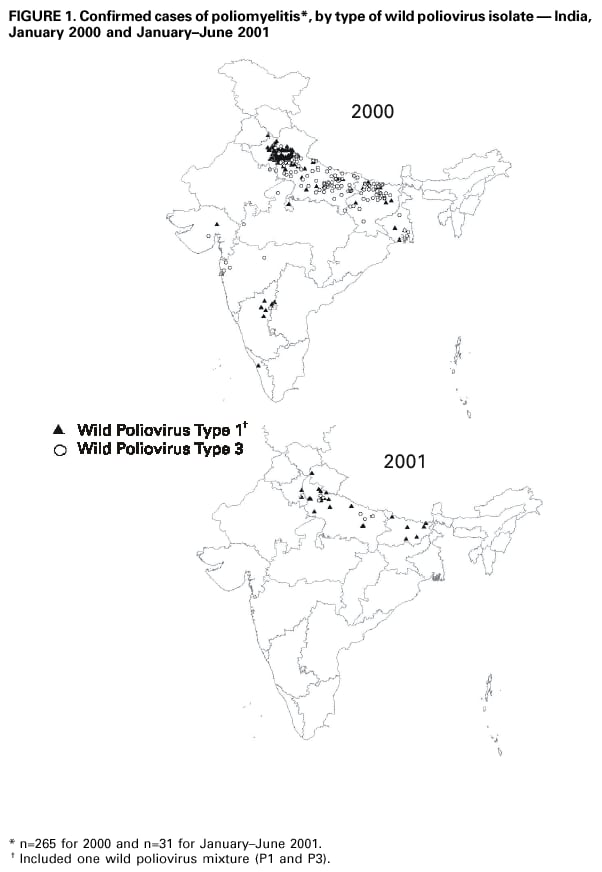

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Progress Toward Poliomyelitis Eradication --- South-East Asia, January 2000--June 2001Since the World Health Assembly resolved in 1988 to eradicate poliomyelitis globally (1), the estimated number of polio cases worldwide has declined 99%. During 1994, member countries of the South-East Asia Region (SEAR)* of the World Health Organization (WHO) began accelerating efforts to eradicate polio. By 2000 (2), wild poliovirus was detected in only four of the 10 countries: Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Myanmar. This report summarizes polio eradication activities during January 2000--June 2001 in SEAR, where wild poliovirus transmission has declined rapidly and is occurring primarily in northern India. Routine VaccinationDuring 2000, the Indian government reported that the routine administrative coverage rate with three doses of oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV3) among children aged 1 year was 95%; however, Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey data suggested that coverage was approximately 59% in India (United Nations Children's Fund [UNICEF], unpublished data, 2000)†. Similar surveys found coverage rates of approximately 67% in Bangladesh and 60% in Nepal. Routine administrative OPV3 coverage rates were reported from Bangladesh (90%), Bhutan (90%), Democratic People's Republic (DPR) of Korea (91%), Indonesia (66%), Maldives (98%), Myanmar (86%), Nepal (80%), Sri Lanka (102%), and Thailand (89%). Supplementary VaccinationDuring the second half of 2000 and the first half of 2001, all countries in the region implemented at least two rounds of national immunization days (NIDs) (mass campaigns over a period of days to weeks in which two doses of OPV are administered to all children usually aged <5 years regardless of previous vaccination history with an interval of 4--6 weeks between doses). On the basis of May 1999 recommendations (3), India conducted four NID rounds (October 1999--January 2000) followed 1 month later by two rounds of subnational immunization days (SNIDs) (same procedure as NIDs but in a smaller area) in eight high-risk northern states. Two additional SNID rounds and two NID rounds were conducted in fall and winter 2000--2001. In addition to the use of fixed vaccination posts, the NID and SNID rounds in Bangladesh, India, and Nepal were intensified through door-to-door and boat-to-boat vaccine delivery. NIDs and SNIDs in Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Nepal were synchronized to coincide with India. During 2000, in response to the detection of wild poliovirus, mop-up campaigns began in India, Myanmar, and Nepal. In India, eight mop-up campaigns were conducted targeting 22.7 million children. During spring (low transmission season) 2001, two OPV doses were administered in high-risk areas to children aged <5 years, including 20.2 million in 40 districts of Uttar Pradesh, 9.5 million in 18 districts of Bihar, and 3.7 million in five districts of West Bengal. Eleven additional mop-up campaigns were completed or were planned by June. Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) SurveillanceThe goal of AFP surveillance is to detect circulating polioviruses and provide data for developing appropriate supplementary vaccination strategies. AFP surveillance is evaluated by two key indicators: sensitivity of reporting (target: nonpolio AFP rate of >1 case per 100,000 children aged <15 years) and completeness of specimen collection (target: two adequate stool specimens from >80% of all persons with AFP cases). In Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, and Nepal, AFP detection is facilitated through surveillance medical officers (SMOs) who receive training and are responsible for a defined area. Myanmar had nine officers and Nepal had six. By June 2001, Bangladesh had 32 and India had 207. Surveillance in Bangladesh, India, and Nepal was strengthened by the Stop the Transmission of Polio (STOP) teams§. The reported number of AFP cases during 1999--2000 increased in Bangladesh (from 767 to 1133) and Myanmar (from 183 to 294); both countries had a nonpolio AFP rate >1.0 for the first time (Table 1). India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Thailand maintained nonpolio AFP rates >1.0. In Indonesia, the rate decreased from 0.99 in 1999 to 0.85 in 2000. During 2001, the nonpolio AFP rate continued to be >1.0 in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Thailand; however, the rate decreased to 0.46 in Indonesia. During 2000, the percentage of adequate stool specimens¶ collected from persons with AFP was >80% in India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. Specimen collection increased during 1999--2000 in Bangladesh (from 48% to 68%), DPR Korea (from 33% to 74%), Myanmar (from 66% to 74%), and Nepal (from 76% to 79%). During 2001, sewage sampling in Mumbai, Maharashtra, India, detected wild poliovirus type 1 that was linked genetically to poliovirus previously isolated in Uttar Pradesh. Polio IncidenceDuring 1999--2000, the incidence of wild virus-confirmed polio cases decreased in SEAR from 1161 to 272, primarily reflecting the decreases in India (from 1126 to 265). In India, the greatest decline occurred in central and southern states. Of 265 virus-confirmed cases in India in 2000, 138 (52%) were poliovirus type 1 (P1), 126 (48%) were poliovirus type 3 (P3), and one case was a mixture of P1 and P3 (Figure 1). The last reported case of wild poliovirus type 2 in the world was isolated from an AFP case from India in October 1999 (Aligarh District, Uttar Pradesh). The number of polio cases reported from Bangladesh decreased from 393 (29 virus-confirmed) in 1999 to 197 (one virus-confirmed) in 2000. During that year, wild viruses also were isolated from two cases in Myanmar (along the border with Bangladesh) and from four cases in Nepal (along the border with India). By June 30, 2001, 31 virus-confirmed polio cases had been detected in the four northern states of Bihar, Delhi, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh in India; and no virus had been found elsewhere in SEAR. Laboratory NetworkThe Polio Laboratory Network for SEAR consists of 17 laboratories (nine in India, three in Indonesia, and one each in Bangladesh, DPR Korea, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Thailand). The network includes 14 national polio laboratories, two regional reference laboratories, and one global specialized laboratory that conducts genetic sequencing. As of June, 16 laboratories were fully accredited. Reported by: Vaccines and Biologicals Dept, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, New Delhi, India. Vaccines and Biologicals Dept, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Respiratory and Enterovirus Br, Div of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases; Vaccine Preventable Disease Eradication Div, National Immunization Program, CDC. Editorial Note:The increase in SEAR polio eradication activities during the past 18 months has resulted in a dramatic reduction in polio cases. This progress has been accompanied by enhanced surveillance that improves the completeness of reporting. During January--June 2001, wild poliovirus circulated in only four states in India, with intense transmission in western Uttar Pradesh. Interrupting the remaining chains of transmission through supplementary vaccination activities is the highest priority in SEAR. Viruses isolated from AFP cases in Myanmar and Nepal along the border with India in 2000 were genetically similar to those from Bangladesh and India during 1999, underscoring the importance of border areas in virus transmission. Continuous cooperation among neighboring countries both in AFP surveillance and synchronization of supplementary vaccination activity is needed (4). The immediate concern in India is improvement in supplementary vaccination activities in the four contiguous states of Bihar, Delhi, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh to compensate for high birth rates, crowded urban conditions, poor sanitation and infrastructure, low routine vaccination coverage, and insufficient health personnel. The SEAR Technical Consultative Group meeting in May 2001 called for 1) Increased prioritization of AFP cases highly suspected of being true polio cases; 2) prompt supplementary vaccination campaigns in areas with wild poliovirus transmission; 3) prompt reporting of AFP cases, timely laboratory results, and regular analysis of data; and 4) establishment of national expert review committees in SEAR countries. Although AFP surveillance has improved in Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, and Nepal through the SMO network (5), surveillance remains suboptimal in DPR Korea, and AFP performance indicators have declined in Indonesia. Assessments of AFP surveillance by WHO and the ministries of health were conducted in India and Nepal in 2001. The review concluded that the existing surveillance system is unlikely to miss areas in India with sustained wild poliovirus transmission. The review recommended implementation of the mopping-up plan, regular active AFP searches by the reporting units, greater private sector involvement, regular analysis of surveillance data for programmatic action, addressing vacancies of key district government posts, and strengthening project management at national and regional levels. AFP surveillance reviews in Bangladesh and DPR Korea are planned for late 2001. Intensive and well-planned supplementary vaccination activity may interrupt wild poliovirus transmission during the next 6--12 months in SEAR following the example of the Region of Americas in 1991, the Western Pacific Region in 1997, and the European Region in 1998 (6--8). If interruption of wild poliovirus occurs in SEAR before the end of 2002, global certification is possible in 2005 (9). References**

* Bangladesh, Bhutan, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, India, Indonesia, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. † Vaccination coverage determined by the administrative method (in which the doses administered is the numerator and the estimated number of target children is the denominator) is often higher than coverage determined through surveys because of overestimates in the number of doses of vaccine administered and underestimates of the size of the target population. § Groups of international health-care professionals deployed to a local area for 3 months to assist ministry of health staff with polio eradication activities. ¶ Two stool specimens collected at least 24 hours apart within 14 days from onset of paralysis and shipped adequately to the laboratory. ** All MMWR references are available on the Internet at <http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr>. Use the search function to find specific articles. Table 1  Return to top. Figure 1  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 8/31/2001 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 8/31/2001

|