|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

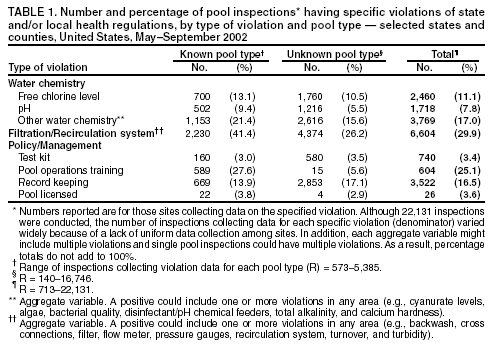

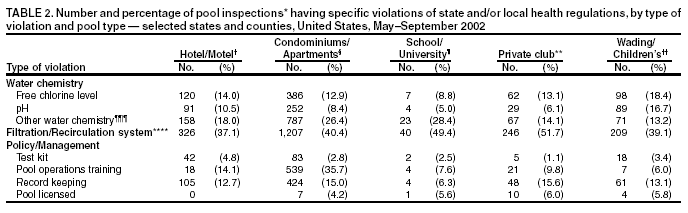

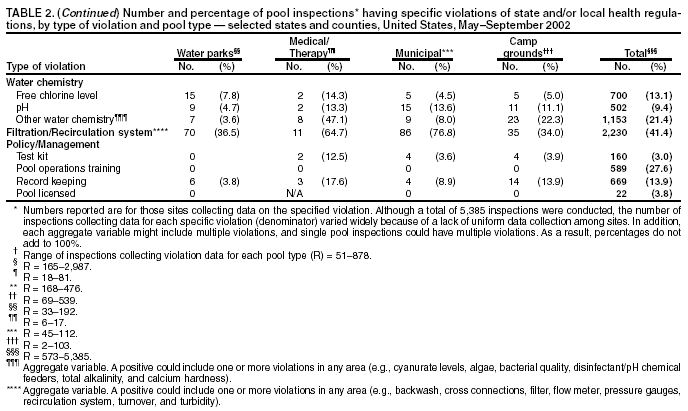

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Surveillance Data from Swimming Pool Inspections --- Selected States and Counties, United States, May--September 2002Swimming is the second most popular exercise activity in the United States, with approximately 360 million annual visits to recreational water venues (1). This exposure increases the potential for the spread of recreational water illnesses (RWIs) (e.g., cryptosporidiosis, giardiasis, and shigellosis). Since the 1980s, the number of reported RWI outbreaks has increased steadily (2). Local environmental health programs inspect public and semipublic pools periodically to determine compliance with local and state health regulations. During inspections for regulatory compliance, data pertaining to pool water chemistry, filtration and recirculation systems, and management and operations are collected. This report summarizes pool inspection data from databases at six sites across the United States collected during May 1--September 1, 2002. The findings underscore the utility of these data for public-health decision making and the need for increased training and vigilance by pool operators to ensure high-quality swimming pool water for use by the public. Data from 22,131 pool inspections were collected from the Allegheny County Department of Health, Pennsylvania (n = 713); the Florida Department of Health, Bureau of Water Programs (n = 19,604); the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, California (n = 1,606); the St. Louis County Department of Public Health, Minnesota (n= 34); the City of St. Paul Office of License, Inspections, and Environmental Protection, St. Paul, Minnesota (n = 56); and the Wyoming Department of Agriculture (n = 118). The sites selected were a convenience sample of pool inspection programs contacted that had computerized data available. Because of data incompatibilities, some inspections conducted at some sites might not have been part of the final analysis. The data were merged into a single SAS database, including date of inspection, pool type, water-chemistry data (e.g., free chlorine and pH levels), filtration and recirculation system data (e.g., operating filters and approved water turnover rates), and policy and management data (e.g., record keeping and pool operator training). A violation was noted when an inspection item was not in compliance with state or local swimming pool codes. Other inspection items (e.g., support facilities and injury control) were not addressed in this study. A total of 21,561 violations of pool codes were documented during the 22,131 inspections; the majority (67.5%) occurred in pools for which no pool type (e.g., hotel/motel) was specified (Table 1). Approximately one half (45.9%) of inspections indicated no violations. The majority of inspections (54.1%) found one or more violations (median: one; range: one to 12), and 8.3% of inspections resulted in immediate closure of the pool pending corrections of serious violation items (e.g., lack of disinfectant). Of total violations, water-chemistry violations comprised 38.7%, followed by filtration and recirculation system (38.6%), and policy and management (22.7%). For the 24.3% of inspections for which pool type could be ascertained (typed inspections), a range of violations occurred (Table 2). For typed inspections collecting free chlorine data, 4.5%--18.4% reported violations. The highest percentage (18.4%) of violations occurred in child wading pools, medical/therapy pools (14.3%), and hotel/motel pools (14.0%). In typed inspections, the percentage of total violations attributable to pH infractions ranged from 4.7% to 16.7%, with the highest percentage occurring in child wading pools. For child wading pools, 8% had coincident free chlorine and pH violations. Filtration and recirculation system violations occurred in 34.0%--76.8% of typed inspections, with municipal pools having the greatest percentage. In sites where training was required, inspections demonstrated that many pool operators did not have appropriate certification (0--35.7%), with apartment/condominium complexes having the highest percentage of violations. Reported by: D Cinpinski, MPA, Allegheny County Dept of Health, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. B Bibler, Bur of Water Programs, Florida Dept of Health. R Kebabjian, MPH, Los Angeles County, Dept of Health Svcs, Recreational Health Program, Los Angeles, California. R Georgesen, St. Louis County Dept of Public Health; P Kishel, City of St. Paul Office of License, Inspections, and Environmental Protection, St. Paul, Minnesota. D Finkenbinder, MPA, N Bloomenrader, Wyoming Dept of Agriculture. C Otto, MPA, Div of Emergency and Environmental Health Svcs, National Center for Environmental Health; MJ Beach, PhD, J Roberts, MPH, L Mirel, MS, Div of Parasitic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases; K Day, MPH, K Bauer, MS, Public Health Prevention Svc, CDC. Editorial Note:The increasing number of reported pool-associated outbreaks of gastroenteritis underscores the need for proper pool maintenance as an important public health intervention (1,2). Approximately one fourth of these outbreaks involved chlorine-sensitive pathogens (e.g., Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Shigella spp.), which causally implicates inadequate pool maintenance and disinfection. Pool inspections are the primary means of ensuring appropriate pool operation, but resources generally allow only one to three annual inspections of each pool. As a result, pool operators are responsible for maintaining their pools with minimal public health oversight. This report documents the first attempt to analyze aggregated pool inspection data, which indicate that although some pools are well-maintained, such an infrequent inspection process cannot ensure compliance with state and local pool regulations. Proper pool maintenance requires a combination of good water quality, functioning filtration and recirculation equipment, and well-trained staff. In this study, several violations that could facilitate the spread of RWIs were documented, with 45.9% of inspections documenting no violations. The majority of violations involved water-quality parameters (e.g., free chlorine and pH levels) or filtration and recirculation system parameters. The interaction of pH and free chlorine levels is critical in determining the effectiveness of chlorine as a disinfectant, and effective monitoring can ensure that the optimum free chlorine and pH levels are maintained to prevent infectious disease transmission. The coincident occurrence of pH and chlorine violations indicates a substantial lack of training among pool operators, particularly those at apartment/condominium complexes. The number of overall violations highlights the need for increased vigilance in ensuring pool staff training, including information about RWI transmission, and the potential benefits of mandating training for pool operators throughout the United States. This poses a challenge for some pool types (e.g., apartment/condominium complexes and hotels/motels) because of high staff turnover or part-time operators. Providing pool operators with more targeted education, maintenance suggestions, and forms for simple monitoring of free chlorine and pH levels might improve public health protection at these facilities. Chlorine and pH violations were highest in wading pools, which are used by younger children, including those who wear diapers. Young children, who often swallow water indiscriminately and have an increased chance of contaminating the pool water fecally, are at increased risk for severe illness if infected. In addition, the shallow depth and relatively low volume of water in these wading pools might lead to more rapid depletion of disinfectant by ultraviolet light and higher organic contamination by the children. Wading pools require increased vigilance and testing to maintain safe disinfectant levels. Pool operators need to be aware that every time they have inadequate disinfection in a pool, they increase the risk for spreading RWIs whenever an infected swimmer contaminates the pool. The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, database structures for each site differed, the types of data collected and entered varied, and the data were not standardized across states or counties, thereby reducing the generalizability of the data. Second, because free chlorine levels were not entered in the database, the percentage of violations caused by low chlorine levels could not be ascertained and the range of chlorine levels recorded could not be analyzed. Although the lack of uniform data collection among sites limited the analysis and usability of the data, this report underscores the potential usefulness of uniform collection of these data in a computerized format that can be analyzed routinely and used for full evaluation of inspection programs. CDC and its partners are developing systems-based guidance on pool operation and implementation of uniform methods for data collection and analysis. These data can then be used in the training of inspectors and operators, planning and resource allocation, and documenting trends related to particular regulatory changes and interventions. Poor pool maintenance and operation, untrained pool staff, the potential presence of the chlorine-resistant pathogen Cryptosporidium parvum (2,3), and a swimming public that is ill-informed about the potential for spreading RWIs in the pool increase the complexity of any proposed prevention plan. Swimmer education should play a critical role in preventing the spread of RWIs. Swimmers and home pool owners should be informed that they should 1) not swim when ill with diarrhea, 2) not swallow pool water, and 3) practice good hygiene when using a pool (e.g., frequent restroom breaks, appropriate diaper changing, and hand washing). Additional information about reducing the spread of RWIs is available at http://www.healthyswimming.org. References

Return to top. Table 2

Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 6/5/2003 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 6/5/2003

|