|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Recommendations for Identification and Public Health Management of Persons with Chronic Hepatitis B Virus InfectionPrepared by

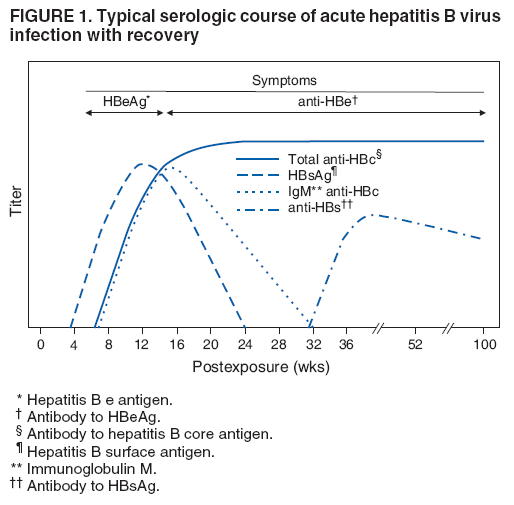

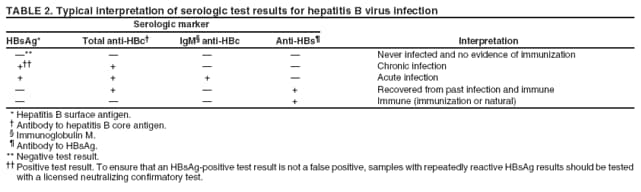

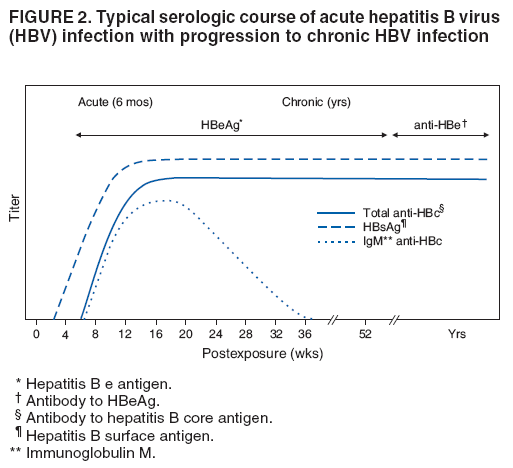

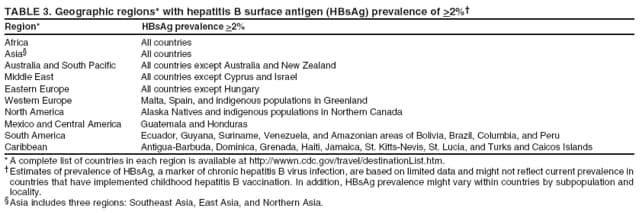

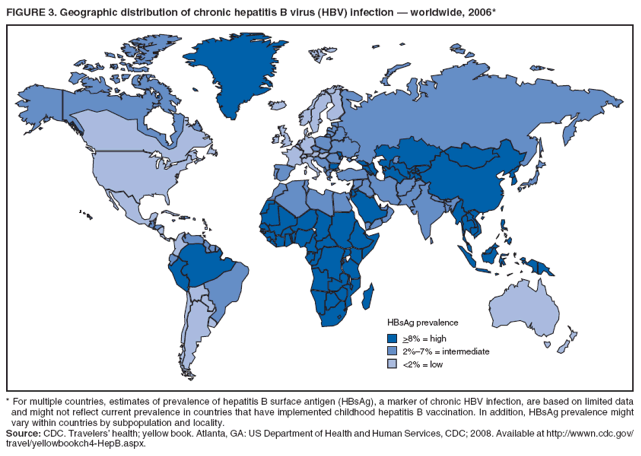

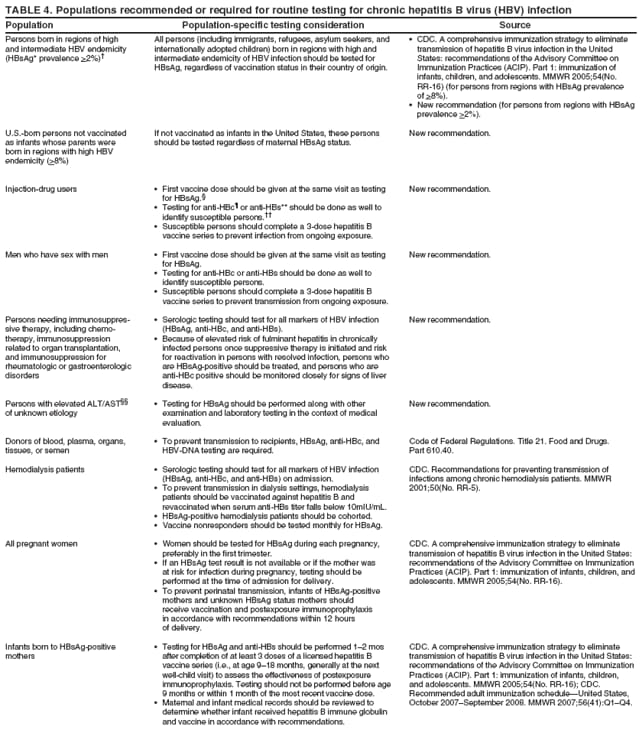

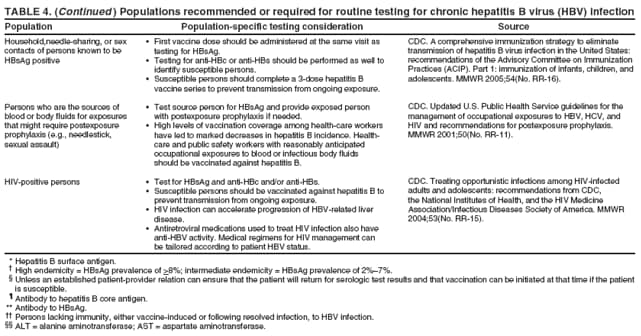

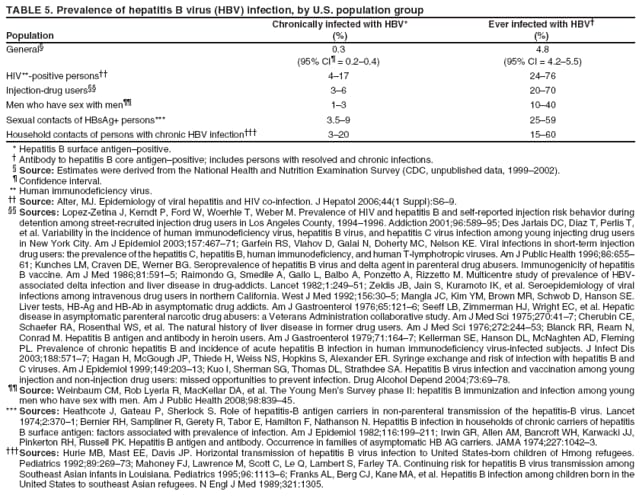

The material in this report originated in the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Kevin Fenton, MD, Director, and the Division of Viral Hepatitis, John Ward, MD, Director. Corresponding preparer: Cindy M. Weinbaum, MD, Division of Viral Hepatitis, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, 1600 Clifton Road, MS G-37, Atlanta GA 30333. Telephone: 404-718-8596; Fax: 404-718-8595; email: [email protected]. SummarySerologic testing for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is the primary way to identify persons with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Testing has been recommended previously for pregnant women, infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers, household contacts and sex partners of HBV-infected persons, persons born in countries with HBsAg prevalence of >8%, persons who are the source of blood or body fluid exposures that might warrant postexposure prophylaxis (e.g., needlestick injury to a health-care worker or sexual assault), and persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. This report updates and expands previous CDC guidelines for HBsAg testing and includes new recommendations for public health evaluation and management for chronically infected persons and their contacts. Routine testing for HBsAg now is recommended for additional populations with HBsAg prevalence of >2%: persons born in geographic regions with HBsAg prevalence of >2%, men who have sex with men, and injection-drug users. Implementation of these recommendations will require expertise and resources to integrate HBsAg screening in prevention and care settings serving populations recommended for HBsAg testing. This report is intended to serve as a resource for public health officials, organizations, and health-care professionals involved in the development, delivery, and evaluation of prevention and clinical services. IntroductionChronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a common cause of death associated with liver failure, cirrhosis, and liver cancer. Worldwide, approximately 350 million persons have chronic HBV infection, and an estimated 620,000 persons die annually from HBV-related liver disease (1,2). Hepatitis B vaccination is highly effective in preventing infection with HBV and consequent acute and chronic liver disease. In the United States, the number of newly acquired HBV infections has declined substantially as the result of the implementation of a comprehensive national immunization program (3--5). However, the prevalence of chronic HBV infection remains high; in 2006, approximately 800,000--1.4 million U.S. residents were living with chronic HBV infection (Table 1), and hepatitis B is the underlying cause of an estimated 2,000--4,000 deaths each year in the United States (6). Improving the identification and public health management of persons with chronic HBV infection can help prevent serious sequelae of chronic liver disease and complement immunization strategies to eliminate HBV transmission in the United States. Persons with chronic HBV infection can remain asymptomatic for years, unaware of their infections and of their risks for transmitting the virus to others and for having serious liver disease later in life. Early identification of persons with chronic HBV infection permits the identification and vaccination of susceptible household contacts and sex partners, thereby interrupting ongoing transmission. All persons with chronic HBV infection need medical management to monitor the onset and progression of liver disease and liver cancer. Safe and effective antiviral agents now are available to treat chronic hepatitis B, providing a greater imperative to identify persons who might benefit from medical evaluation, management, and antiviral therapy and other treatment when indicated. The majority of the medications now in use for hepatitis B treatment were approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002 or later; two forms of alfa 2 interferon and five oral nucleoside/nucleotide analogues have been approved, and other medications are in clinical trials. Serologic testing for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is the primary way to identify persons with chronic HBV infection. Because of the availability of effective vaccine and postexposure prophylaxis, CDC previously recommended HBsAg testing for pregnant women, infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers, household contacts and sex partners of HBV-infected persons, persons born in countries with HBsAg prevalence of >8%, and persons who are the source of blood or body fluid exposures that might warrant postexposure prophylaxis (e.g., needlestick injury to a health-care worker or sexual assault), and persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (4,5,7--11). This report updates and expands these multiple previous CDC guidelines for HBsAg testing and includes new recommendations for public health evaluation and management of chronically infected persons and their contacts. Routine HBsAg testing now is recommended for persons born in geographic regions in which HBsAg prevalence is >2%, men who have sex with men (MSM), and injection-drug users (IDUs). MethodsDuring February 7--8, 2007, CDC convened a meeting of researchers, physicians, state and local public health professionals, and other persons in the public and private sectors with expertise in the prevention, care, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B. These consultants reviewed available published and unpublished epidemiologic and treatment data, considered whether to recommend testing specific new populations for HBV infection, and discussed how best to implement new and existing testing strategies. Topics discussed included 1) the changing epidemiology of chronic HBV infection, 2) health disparities caused by the disproportionate HBV-related morbidity and mortality among persons infected as infants and young children in countries with high levels of HBV endemicity, and 3) the increasing benefits of care and opportunities for prevention for infected persons and their contacts. On the basis of this discussion, CDC determined that reconsideration of current guidelines was warranted. This report summarizes current HBsAg testing recommendations published previously by CDC, expands CDC recommendations to increase the identification of chronically infected persons in the United States, and defines the components of programs needed to identify HBV-infected persons successfully. Clinical Features and Natural History of HBV InfectionHBV is a 42-nm DNA virus in the Hepadnaviridae family. After a susceptible person is exposed, the virus is transported by the bloodstream to the liver, which is the primary site of HBV replication. HBV infection can produce either asymptomatic or symptomatic infection. When clinical manifestations of acute disease occur, illness typically begins 2--3 months after HBV exposure (range: 6 weeks--6 months). Infants, children aged <5 years, and immunosuppressed adults with newly acquired HBV infection typically are asymptomatic; 30%--50% of other persons aged >5 years have clinical signs or symptoms of acute disease after infection. Symptoms of acute hepatitis B include fatigue, poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, low-grade fever, jaundice, dark urine, and light stool color. Clinical signs include jaundice, liver tenderness, and possibly hepatomegaly or splenomegaly. Fatigue and loss of appetite typically precede jaundice by 1--2 weeks. Acute illness typically lasts 2--4 months. The case-fatality rate among persons with reported cases of acute hepatitis B is approximately 1%, with the highest rates occurring in adults aged >60 years (12). Primary HBV infection can be self-limited, with elimination of virus from blood and subsequent lasting immunity against reinfection, or it can progress to chronic infection with continuing viral replication in the liver and persistent viremia. Resolved primary infection is not a risk factor for subsequent occurrence of chronic liver disease or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, patients with resolved infection who become immunosuppressed (e.g., from chemotherapy or medication) might, albeit rarely, experience reactivation of hepatitis B with symptoms of acute illness (13--15). HBV DNA has been detected in the livers of persons without serologic markers of chronic infection after resolution of acute infection (13,16--19). The risk for progression to chronic infection is related inversely to age at the time of infection. HBV infection becomes chronic in >90% of infants, approximately 25%--50% of children aged 1--5 years, and <5% of older children and adults) (13,20--23). Immunosuppressed persons (e.g., hemodialysis patients and persons with HIV infection) are at increased risk for chronic infection (22). Once chronic HBV infection is established, 0.5% of infected persons spontaneously resolve infection annually (indicated by the loss of detectable HBsAg and serum HBV DNA and normalization of serum alanine aminotransferase [ALT] levels); resolution is rarer among children than among adults (13,24,25). Persons with chronic HBV infection can be asymptomatic and have no evidence of liver disease, or they can have a spectrum of disease, ranging from chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis or liver cancer. Chronic infection is responsible for the majority of cases of HBV-related morbidity and mortality; follow-up studies have demonstrated that approximately 25% of persons infected with HBV as infants or young children and 15% of those infected at older ages died of cirrhosis or liver cancer. The majority remained asymptomatic until onset of cirrhosis or end-stage liver disease (26). Persons with histologic evidence of chronic hepatitis B (e.g., hepatic inflammation and fibrosis) are at higher risk for HCC than HBV-infected persons without such evidence (27). Potential extrahepatic complications of chronic HBV infection include polyarteritis nodosa (28,29), membranous glomerulonephritis, and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (30). Serologic Markers of HBV InfectionThe serologic patterns of chronic HBV infection are varied and complex. Antigens and antibodies associated with HBV infection include HBsAg and antibody to HBsAg (anti-HBs), hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) and antibody to HBcAg (anti-HBc), and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and antibody to HBeAg (anti-HBe). Testing also can be performed to assess the presence and concentration of circulating HBV DNA. At least one serologic marker is present during each of the different phases of HBV infection (Figures 1 and 2) (31). Serologic assays are available commercially for all markers except HBcAg, because no free HBcAg circulates in blood. No rapid or oral fluid tests are licensed in the United States to test for any HBV markers. Three phases of chronic HBV infection have been recognized: the immune tolerant phase (HBeAg-positive, with high levels of HBV DNA but absence of liver disease), the immune active or chronic hepatitis phase (HBeAg-positive, HBeAg-negative, or anti-HBe-positive, with high levels of HBV DNA and active liver inflammation), and the inactive phase (anti-HBe positive, normal liver aminotransferase levels, and low or absent levels of HBV DNA) (32). Patients can evolve through these phases or revert from inactive hepatitis B back to immune active infection at any time. The serologic markers typically used to differentiate among acute, resolving, and chronic infection are HBsAg, IgM anti-HBc, and anti-HBs (Table 2). The presence of HBeAg and HBV DNA generally indicates high levels of viral replication; the presence of anti-HBe usually indicates decreased or undetectable HBV DNA and lower levels of viral replication. In newly infected persons, HBsAg is the only serologic marker detected during the first 3--5 weeks after infection. The average time from exposure to detection of HBsAg is 30 days (range: 6--60 days) (31,33). Highly sensitive single-sample nucleic acid tests can detect HBV DNA in the serum of an infected person 10--20 days before detection of HBsAg (34). Transient HBsAg positivity has been reported for up to 18 days after hepatitis B vaccination and is clinically insignificant (35,36). Anti-HBc appears at the onset of symptoms or liver-test abnormalities in acute HBV infection and persists for life in the majority of persons. Acute or recently acquired infection can be distinguished from chronic infection by the presence of the immunoglobulin M (IgM) class of anti-HBc, which is detected at the onset of acute hepatitis B and persists for up to 6 months if the infection resolves. In patients with chronic HBV infection, IgM anti-HBc can persist during viral replication at low levels that typically are not detectable by the assays used in the United States. However, persons with exacerbations of chronic infection can test positive for IgM anti-HBc (37). Because the positive predictive value of this test is low in asymptomatic persons, IgM anti-HBc testing for diagnosis of acute hepatitis B should be limited to persons with clinical evidence of acute hepatitis or an epidemiologic link to a person with HBV infection. In persons who recover from HBV infection, HBsAg and HBV DNA usually are eliminated from the blood, and anti-HBs appears. In persons who become chronically infected, HBsAg and HBV DNA persist. In persons in whom chronic infection resolves, HBsAg becomes undetectable; anti-HBc persists and anti-HBs will occur in the majority of these persons (38,39). In certain persons, total anti-HBc is the only detectable HBV serologic marker. Isolated anti-HBc positivity can represent 1) resolved HBV infection in persons who have recovered but whose anti-HBs levels have waned, most commonly in high-prevalence populations; 2) chronic infection in which circulating HBsAg is not detectable by commercial serology, most commonly in high-prevalence populations and among persons with HIV or HCV infection (40) (HBV DNA has been isolated from the blood in <5% of persons with isolated anti-HBc) (40,41); or 3) false-positive reaction. In low-prevalence populations, isolated anti-HBc may be found in 10%--20% of persons with serologic markers of HBV infection, most of whom will demonstrate a primary response after hepatitis B vaccination(42,43). Persons positive only for anti-HBc are unlikely to be infectious except under unusual circumstances in which they are the source for direct percutaneous exposure of susceptible recipients to substantial quantities of virus (e.g., blood transfusion or organ transplant) (44). HBeAg can be detected in the serum of persons with acute or chronic HBV infection. In the majority of those with chronic infection, HBeAg is cleared over time, and anti-HBe appears (45--49). Presence of HBeAg correlates with more active disease: patients with HBeAg typically have high levels of HBV DNA (106--1010 IU/mL), whereas those who are HBeAg-negative and anti-HBe-positive generally have low or only modest HBV DNA levels (0--105 IU/mL). Epidemiology of HBV Infection in the United StatesTransmissionHBV is transmitted by percutaneous and mucosal exposure to infectious blood or body fluids. The highest concentrations of virus are found in blood; however, semen and saliva also have been demonstrated to be infectious (50). HBV remains viable and infectious in the environment for at least 7 days and can be present in high concentrations on inanimate objects, even in the absence of visible blood (13,51). Persons with chronic HBV infection are the major source of new infections, and the primary routes of HBV transmission are sexual contact, percutaneous exposure to infectious body fluids (such as occurs through needle sharing by IDUs or needlestick injuries in health-care settings), perinatal exposure to an infected mother, and prolonged, close personal contact with an infected person (e.g., via contact with exudates from dermatologic lesions, contact with contaminated surfaces, or sharing toothbrushes or razors), as occurs in household contact (5,52). No evidence exists of transmission of HBV by casual contact in the workplace, and transmission occurs rarely in childcare settings (4). Few cases have been reported in which health-care workers have transmitted infection to patients, particularly since implementation of standard universal infection control precautions (53). Incidence of HBV InfectionDuring 1985--2006, incidence of acute hepatitis B in the United States declined substantially, from 11.5 cases per 100,000 population in 1985 to 1.6 in 2006 (12). The actual incidence of new HBV infections is estimated to be approximately tenfold higher than the reported incidence of acute hepatitis B, after adjustment for underreporting of cases and asymptomatic infections. In 2006, an estimated 46,000 persons were newly infected with HBV (54). The greatest declines in incidence of acute disease have occurred in the cohorts of children for whom infant and adolescent catch-up vaccination was recommended (12). Among children aged <15 years, incidence of hepatitis B declined 98% during 1990--2006, from 1.2 per 100,000 population in 1990 to 0.02 in 2006 (12). This decline reflects the effective implementation of hepatitis B vaccination in the United States. Since 2001, fewer than 30 cases of acute hepatitis B have been reported annually in children born in 1991 or later, the majority of whom were international adoptees or children born outside the United States who were not fully vaccinated (55). In 2006, adults aged >20 years had the highest incidence of acute HBV infection, reflecting low hepatitis B vaccination coverage among adults with behavioral risks for HBV infection (e.g., MSM, IDUs, persons with multiple sex partners, and persons whose sex partners are infected with HBV) (12). Prevalence of HBV Infection and Its SequelaeU.S. mortality data for 2000--2003 indicated that HBV infection was the underlying cause of an estimated 2,000--4,000 deaths annually. The majority of these deaths resulted from cirrhosis and liver cancer (6; CDC, unpublished data, 2000--2003). The burden of chronic HBV infection in the United States is greater among certain populations as a result of earlier age at infection, immune suppression, or higher levels of circulating infection. These include persons born in geographic regions with high (>8%) or intermediate (2%--7%) prevalence of chronic HBV infection, HIV-positive persons (who might have additional risk factors) (56--58), and certain adult populations for whom hepatitis B vaccination has been recommended because of behavioral risks (e.g., MSM and IDUs). An accurate estimate of the prevalence of chronic HBV infection in the United States must be derived from multiple sources of data to account for the disproportionate contributions of persons of foreign birth, members of certain ethnic minority populations, and persons with certain medical conditions (Table 1). For the U.S.-born civilian noninstitutionalized population, prevalence estimates can be obtained from the most recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which was conducted during 1999--2004 (available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm). Because data from studies of foreign-born U.S. residents indicate that HBsAg seroprevalence corresponds to HBV endemicity in the country of origin (5), for the foreign-born population residing in the United States, HBV prevalence estimates were derived by applying country-specific prevalence estimates gathered from the scientific literature and the World Health Organization (2) to the number of foreign-born U.S. residents by their country of birth as reported by the 2006 U.S. Census American Community Survey (59). Other populations for which estimates were calculated included those in correctional institutions and the homeless. Together, these sources indicated that an estimated 800,000--1.4 million persons in the United States have chronic HBV infection. Approximately 0.3%--0.5% of U.S. residents are chronically infected with HBV; 47%--70% of these persons were born in other countries (Table 1). Global Variation in Prevalence of HBV Infection HBV transmission patterns and the seroprevalence of chronic HBV infection vary markedly worldwide, although seroprevalence studies in many countries are limited, and the epidemiology of hepatitis B is changing. Approximately 45% of persons worldwide live in regions in which HBV is highly endemic (i.e., where prevalence of chronic HBV infection is >8% among adults and that of resolved or chronic infection [i.e., anti-HBc positivity] is >60%) (2) (Figure 3). Historically, >90% of new infections occurred among infants and young children as the result of perinatal or household transmission during early childhood (26). Infant immunization programs in many countries have led to marked decreases in incidence and prevalence among younger, vaccinated members of these populations (60--63). Countries of intermediate HBV endemicity (i.e., HBsAg prevalence of 2%--7%) account for approximately 43% of the world's population; in these countries, multiple modes of transmission (i.e., perinatal, household, sexual, injection-drug use, and health-care--related) contribute to the infection burden. Regions of the world with high or intermediate prevalence of HBsAg include much of Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and the Pacific Islands (2,4) (Figure 3 and Table 3). In countries of low endemicity (i.e., HBsAg prevalence of <2%), the majority of new infections occur among adolescents and adults and are attributable to sexual and injection-drug--use exposures. However, in certain areas of low HBV endemicity, prevalence of chronic HBV infection is high among indigenous populations born before routine infant immunization (Table 3). In the United States, marked decreases in the prevalence of chronic HBV infection among younger, vaccinated foreign-born U.S. residents have been observed, most likely as a result of infant immunization programs globally (64). However, the rate of liver cancer deaths in the United States continues to be high among certain foreign-born U.S. populations. For example, the rate of liver cancer deaths is highest among Asians/Pacific Islanders, reflecting the high prevalence of chronic hepatitis B in this population (65,66). Globally, other regions with HBsAg prevalence of >2% also have identified high levels of HBV-associated HCC (67,68). Household Contacts and Sex Partners of Persons With Chronic HBV Infection Serologic testing and hepatitis B vaccination has been recommended since 1982 (69) for household contacts and sex partners of persons with chronic HBV infection because previous studies have determined that 14%--60% of persons living in households with persons with chronic HBV infection have serologic evidence indicating resolved HBV infection, and 3%--20% have evidence indicating chronic infection. The risk for infection is highest among unvaccinated children living with a person with chronic HBV infection in a household or in an extended family setting and among sex partners of chronically infected persons (70--77). Men Who Have Sex With Men During 1994--2000, studies of MSM aged <30 years identified chronic infection in 1.1% of MSM aged 18--24 years (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0--2.2%) (78), 2.1% (95% CI = 1.6%--2.6%) of MSM aged 15--21 years (79), and 2.3% (95% CI = 1.7%--2.8%) of MSM aged 22--29 years (80). In these studies, prevalence was higher (7.4%; 95% CI = 5.3%--9.6%) among young MSM who were HIV-positive than it was among those who were HIV-negative (1.5%; 95% CI = 1.2%--1.9%) (CDC, unpublished data, 2007). Before the introduction of the hepatitis B vaccine in 1982, prevalence of chronic HBV infection among MSM was 4.6%--6.1% (81--83). In recent studies, prevalence of past infection increased with increasing age, suggesting that chronic infection might still be more prevalent among older MSM (79,80). Injection-Drug Users Chronic HBV infection has been identified in 2.7%--11.0% of IDUs in a variety of settings (84--91); HBsAg prevalence of 7.1% (95% CI = 6.3%--7.8%) has been described among IDUs with HIV coinfection (92). IDUs contribute disproportionately to the burden of infection in the United States: in chronic HBV infection registries, 4%--12% of reported chronically infected persons had a history of injection-drug use (93). Prevalence of resolved or chronic HBV infection among IDUs increases with the number of years of drug use and is associated with frequency of injection and with sharing of drug-preparation equipment (e.g., cottons, cookers, and rinse water), independent of syringe sharing (94,95). HIV-Positive Persons As life expectancies for HIV-infected persons have increased with use of highly active antiretroviral therapy, liver disease, much of it related to HBV and HCV infections, has become the most common non-AIDS--related cause of death among this population (56,57,96,97). Chronic HBV infection has been identified in 6%--15% of HIV-positive persons from Western Europe and the United States, including 9%--17% of MSM; 7%--10% of IDUs; 4%--6% of heterosexuals; and 1.5% of pregnant women (58,98,99). This high level of chronic infection reflects both common routes of transmission for HIV and HBV and a higher risk of chronicity after HBV infection in an immunocompromised host (100--102). Persons With Selected Medical Conditions Although population-level studies are lacking to determine HBsAg prevalence among populations with other medical conditions, persons with chronic HBV infection who initiate cytotoxic or immunosuppressive therapy (e.g., chemotherapy for malignant diseases, immunosuppression related to organ transplantation, and immunosuppression for rheumatologic and gastroenterologic disorders) are at risk for HBV reactivation and associated morbidity and mortality (32,101,102). Prophylactic antiviral therapy can prevent reactivation and possible fulminant hepatitis in HBsAg positive patients (13,101). Rationale for Testing to Identify Persons With Chronic HBV InfectionAlthough limited data are available regarding the number of persons with chronic HBV infection in the United States who are unaware of their infection status, studies of programs conducting HBsAg testing among Asian-born persons living in the United States indicated that approximately one third of infected persons were unaware of their HBV infection (5,103--105). Published studies for other populations are lacking. Prompt identification of chronic infection with HBV is essential to ensure that infected persons receive necessary care to prevent or delay onset of liver disease and services to prevent transmission to others. Treatment guidelines for chronic hepatitis B have been issued (13,106,107), and multiple medications have been approved for treatment of adults with chronic HBV infection. With recent advances in hepatitis B treatment and detection of liver cancer, identification of an HBV-infected person permits the implementation of important interventions to reduce morbidity and mortality, including

Identification of infected persons also allows for primary prevention of ongoing HBV transmission by enabling persons with chronic infection to adopt behaviors that reduce the risk of transmission to others and by permitting identification of close contacts who require testing and subsequent vaccination (if identified as susceptible) or medical management (if identified as having chronic HBV infection). Appropriate HBsAg testing and counseling also help prevent health-care--associated transmission in dialysis settings by allowing for cohorting of infected patients (112). Testing donated blood and donors of organs and tissues prevents infectious materials from being used and allows unvaccinated persons exposed to needlesticks to receive additional postexposure prophylaxis if the source of the exposure was HBV-infected (113). Testing for chronic HBV infection meets established public health screening criteria (114). Screening is a basic public health tool used to identify unrecognized health conditions so treatment can be offered before symptoms occur and, for communicable diseases, so interventions can be implemented to reduce the likelihood of continued transmission (114). Screening for chronic HBV infection is consistent with the main generally accepted public health screening criteria: 1) chronic hepatitis B is a serious health disorder that can be diagnosed before symptoms occur; 2) it can be detected by reliable, inexpensive, and minimally invasive screening tests; 3) chronically infected patients have years of life to gain if medical evaluation and/or treatment is initiated early, before symptoms occur; and 4) the costs of screening are reasonable in relation to the anticipated benefits (114). The cost-effectiveness of identifying persons with chronic HBV infection cannot be calculated because treatment options constantly are increasing the number of years of disease-free life, and the various treatments have diverse associated costs. However, testing for HBsAg in populations in which prevalence of chronic infection is 2% would cost $750--$3,752 for each chronically infected person identified (range represents $15.01 laboratory cost per test--$75 per screening visit [Marketscan® Database, Ann Arbor, Michigan, unpublished data, 2007]); at higher prevalences, the per-case-identified cost would decrease. This is comparable to the cost of other screening programs. HIV testing in a population with 1% infection prevalence costs $2,133 ([$1,733--$3,733] per positive identified (115); [Marketscan® Database, Ann Arbor, Michigan, unpublished data, 2007] $16 per test [$13--$28]). Another study determined that the cost to identify each new case of diabetes mellitus using a two-step glucose-based screening process in three volunteer clinics in Minnesota was $4,064 per case identified (116). The cost of HBsAg testing in populations with >2% prevalence is substantially lower than the costs per case identified for certain fetal and newborn screening interventions (e.g., screening for newborn hearing disorders [$16,000 per case identified] [117], metabolic disorders [$68,000 per case] [118], neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia [NAIT] caused by anti-HPA-1a [$98,771 per case] [119], or fetal Down syndrome [$690,000 per case] [120]). To prevent HBV transmission, previous guidelines have recommended HBsAg testing for hemodialysis patients, pregnant women, and persons known or suspected of having been exposed to HBV (i.e., infants born to HBV-infected mothers, household contacts and sex partners of infected persons, and persons with known occupational or other exposures to infectious blood or body fluids) (3,112). HBsAg testing also is required for donors of blood, organs, and tissues (113). To guide immunization efforts and identify infected persons, testing also has been recommended previously for persons born in regions with high HBV endemicity (4,121). Finally, testing has been recommended for HIV-positive persons on the basis of their high prevalence of HBV coinfection and their increased risk for HBV-associated morbidity and mortality (122). Because persons with chronic HBV infection serve as the reservoir for new HBV infections in the United States, identification of these persons will complement vaccination strategies for elimination of HBV transmission. With the availability of effective treatments for chronic hepatitis B, the infected person, once identified, can benefit from testing as well. Thus, CDC recommends expanding HBV testing to include all persons born in regions with HBsAg prevalence of >2% (high and intermediate endemicity). CDC also recommends HBsAg testing in addition to vaccination for MSM and IDUs because of their higher-than-population prevalence and their ongoing risk for infection. Finally, to prevent adverse medical outcomes among persons who might be seeking medical care for other reasons, recommendations also are made to test persons with ALT elevations of unknown etiology and candidates for immunosuppressive therapies. RecommendationsPersons who are most likely to be actively infected with HBV should be tested for chronic HBV infection. Testing should include a serologic assay for HBsAg offered as a part of routine care and be accompanied by appropriate counseling and referral for recommended clinical evaluation and care. Laboratories that provide HBsAg testing should use an FDA-licensed or FDA-approved HBsAg test and should perform testing according to the manufacturer's labeling, including testing of initially reactive specimens with a licensed, neutralizing confirmatory test. A confirmed HBsAg-positive result indicates active HBV infection, either acute or chronic; chronic infection is confirmed by the absence of IgM anti-HBc or by the persistence of HBsAg or HBV DNA for at least 6 months. All HBsAg-positive persons should be considered infectious. Recommendations and federal mandates related to routine testing for chronic HBV infection have been summarized (Table 4). To determine susceptibility among persons who are at ongoing risk for infection and recommended for vaccination, total anti-HBc or anti-HBs also should be tested at the time of serologic testing for chronic HBV infection. New populations recommended for testing are the following:

Testing Persons With a History of VaccinationBecause some persons might have been infected with HBV before they received hepatitis B vaccination, HBsAg testing is recommended regardless of vaccination history for the following populations:

Management of Persons Tested for Chronic HBV InfectionVaccination at the Time of TestingPersons to be tested who have been recommended to receive hepatitis B vaccination, including those in settings in which universal vaccination is recommended (i.e., sexually transmitted disease [STD]/HIV testing and treatment facilities, drug-abuse treatment and prevention settings, health-care settings targeting services to IDUs, health-care settings targeting services to MSM, and correctional facilities) should receive the first dose of vaccine at the same medical visit after blood is drawn for testing unless an established patient-provider relation can ensure that the patient will return for serologic test results and that vaccination can be initiated at that time if the patient is susceptible. In venues where vaccination is recommended and testing is not feasible, vaccination still should be provided for all populations for whom it is recommended. Public Health Management of HBsAg-Positive PersonsThe finding of HBsAg in serum is indicative of chronic HBV infection unless the person has signs or symptoms of acute hepatitis. All HBsAg-positive laboratory results should be reported to the state or local health department, in accordance with state requirements for reporting of acute and chronic HBV infection. Chronic HBV infection can be confirmed by verifying the presence of HBsAg in a serum sample taken at least 6 months after the first test, or by the absence of IgM anti-HBc in the original specimen. Standard case definitions for the classification of reportable cases of HBV infection have been published previously (124). Contact ManagementSex partners and household and needle-sharing contacts of HBsAg-positive persons should be identified. Unvaccinated past and present sex partners and household and needle-sharing contacts should be tested for HBsAg and for anti-HBc and/or anti-HBs and should receive the first dose of hepatitis B vaccine as soon as the blood sample for serologic testing has been collected. Susceptible persons should complete the vaccine series using an age-appropriate vaccine dose and schedule. Those who have not been vaccinated fully should complete the vaccine series. Contacts determined to be HBsAg-positive should be referred for medical care. Health-care providers and public health authorities treating persons with chronic HBV infection should obtain the names of their sex contacts and household members and a history of drug use. Providers then can help to arrange for evaluation and vaccination of contacts, either directly or with assistance from state and local health departments. Contact notification is well-established in public STD programs; these programs have the expertise to reach identified contacts of HBsAg-positive patients and might be able to provide guidance on procedures and best practices, or in programs with sufficient capacity, offer assistance to other providers to reach identified contacts. With sufficient resources, identification of contacts should be accompanied by health counseling and include referral of patients and their contacts for other services when appropriate. The success of contact management for hepatitis B has varied widely, depending on local resources. One study determined that approximately half of providers caring for patients with chronic HBV infection recommended contact vaccination, and <20% of contacts initiated vaccination (125). In the national perinatal hepatitis B prevention program, approximately 26% of all persons identified as contacts by HBsAg-positive women were tested and evaluated for vaccination by public health departments (CDC, unpublished data, 2005). In several state and local programs with targeted efforts for adult hepatitis B prevention, up to 85% of identified contacts have been evaluated (CDC, unpublished data, 2005); however, many states and cities have no contact identification programs outside the perinatal hepatitis B prevention program. Given the potential for contact notification to disrupt networks of HBV transmission and reduce disease incidence, health-care providers should encourage patients with HBV infection to notify their sex partners, household members, and injection-drug--sharing contacts and urge them to seek medical evaluation, testing, and vaccination. Patient EducationMedical providers should advise patients identified as HBsAg positive regarding measures they can take to prevent transmission to others and protect their health or refer patients for counseling if needed. Patient education should be conducted in a culturally sensitive manner in the patient's primary language (both written and oral whenever possible). Ideally bilingual, bicultural, medically trained interpreters should be used when indicated.

Other counseling messages include the following:

Medical Management of Chronic Hepatitis BBecause 15%--25% of persons with chronic HBV infection are at risk for premature death from cirrhosis and liver cancer, persons with chronic HBV infection should be evaluated soon after infection is identified by referral to or in consultation with a physician experienced in the management of chronic liver disease. When assessing chronic HBV infection, the physician must consider the level of HBV replication and the degree of liver injury. Injury is assessed using serial tests of serum aminotransferases (ALT and AST), and, when needed, liver biopsy (histologic activity and fibrosis scores). Initial evaluation of patients with chronic HBV infection should include a thorough history and physical examination, with special emphasis on risk factors for coinfection with HIV and HCV, alcohol use, and family history of HBV infection and liver cancer. Laboratory testing should assess for indicators of liver disease (complete blood count and liver panel), markers of HBV replication (HBeAg, anti-HBe, HBV DNA), coinfection with HCV, HDV, and HIV, and antibody to hepatitis A virus (HAV) (if local HAV prevalence makes prevaccination testing cost effective) (109). Where testing is available, schistosomiasis (S. mansoni or S. japonicum) also should be assessed for persons from endemic areas (129) because schistosomiasis might increase progression to cirrhosis or HCC in the presence of HBV infection (130,131). Persons with chronic HBV infection who are not known to be immune to HAV should receive 2 doses of hepatitis A vaccine 6--18 months apart. Baseline alfa fetoprotein assay (AFP) is used to assess for evidence of HCC at initial diagnosis of HBV infection, and ultrasound in patients at risk of HCC (i.e., Asian men aged >40 years, Asian women aged >50 years, persons with cirrhosis, persons with a family history of HCC, Africans aged >20 years, and HBV-infected persons aged >40 years with persistent or intermittent ALT elevation and/or high HBV DNA) (13,108). Liver biopsy (or, ideally, noninvasive markers) can be used to assess inflammation and fibrosis if initial laboratory assays suggest liver damage, as per published practice guidelines for liver biopsy in chronic HBV infection (13). Following an initial evaluation, all patients with chronic HBV infection, even those with normal aminotransferase levels, should receive lifelong monitoring to assess progression of liver disease, development of HCC, need for treatment, and response to treatment. Frequency of monitoring depends on several factors, including family history, age, and the condition of the patient; monitoring schedules have been recommended by several authorities (13,106,107,132). Therapy for hepatitis B is a rapidly changing area of clinical practice. Seven therapies have been approved by FDA for the treatment of chronic HBV infection: interferon alfa-2b, peginterferon alfa-2a, lamivudine, adefovir dipivoxil, entecavir, telbivudine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (13,106,132,133). In addition, at least two other FDA-approved oral antiviral medications for HIV (clevudine and emtricitabine) are undergoing phase-3 trials for HBV treatment and might be approved soon for chronic hepatitis B. Treatment decisions are made on the basis of HBeAg status, HBV DNA viral load, ALT, stage of liver disease, age of patient, and other factors (13,32,134). Coinfection with HIV complicates the management of patients with chronic hepatitis B. When selecting antiretrovirals for HIV treatment, the provider must consider the patient's HBsAg status to avoid liver-associated complications and development of antiviral resistance. Management of these patients has been described elsewhere (135). Serologic endpoints of antiviral therapy are loss of HBeAg, HBeAg seroconversion in persons initially HBeAg positive, suppression of HBV DNA to undetectable levels by sensitive PCR-based assays in patients who are HBeAg-negative and anti-HBe positive, and loss of HBsAg. Optimal duration of therapy has not been established. For HBeAg-positive patients, treatment should be continued for at least 6 months after loss of HBeAg and appearance of anti-HBe (13); for HBeAg-negative/anti-HBe-positive patients, relapse rates are 80%--90% if treatment is stopped in 1--2 years (13). Viral resistance to lamivudine occurs in up to 70% of persons during the first 5 years of treatment (32). Lower rates of resistance among treatment-naïve patients have been observed with adefovir (30% in 5 years), entecavir (<1% at 4 years), and telbivudine (2.3%--5% in 1 year) (136) but more resistance might occur with longer usage or among patients who developed resistance previously to lamivudine. Although combination therapy has not demonstrated a higher rate of response than that using the most potent antiviral medication in the regimen, more studies are needed using combinations of different classes of different medications active against HBV to determine if combination therapy will reduce the rate of the development of resistance. Development of Surveillance Registries of Persons with Chronic HBV InfectionInformation systems, or registries, of persons with chronic HBV infection can facilitate the notification, counseling, and medical management of persons with chronic HBV infection. These registries can be used to distinguish newly reported cases of infection from previously identified cases, facilitate and track case follow-up, enable communication with case contacts and medical providers, and provide local, state, and national estimates of the proportion of persons with chronic HBV infection who have been identified. Public health agencies use registries for patient case management as part of disease control programs for HIV and tuberculosis; for tracking cancers; and for identifying disease trends, treatment successes, and outcomes. Chronic HBV registries can similarly be used as a tool for public health program and clinical management. Widespread registry use for chronic HBV infection will be facilitated by the development of better algorithms for deduplication (i.e., methods to ensure that each infected person is represented only once), routine electronic reporting of laboratory results, and improved communication with laboratories. A tiered approach to establishing a registry might allow programs to increase incrementally the number of data elements collected and the expected extent of follow-up as resources become available. The specific data elements to be included will depend upon the objectives of the registry and the feasibility of collecting that information. At a minimum, sufficient information should be collected to distinguish newly identified persons from those reported previously, including demographic characteristics and serologic test results. If an IgM anti-HBc result is not reported, information about the clinical characteristics of the patient (e.g., presence of symptoms consistent with acute viral hepatitis, date of symptom onset, and results of liver enzyme testing) and the reason for testing can help ensure that the registry includes only persons with chronic infection and excludes those with acute disease. Including data elements on ethnicity and/or country of birth can assist in targeting interventions, and information about contacts identified and managed and medical referrals made can be used to review program needs. Collaboration between the registry and the perinatal hepatitis B prevention program is important to ensure that the registry captures data on women and infants with chronic infection identified through the perinatal hepatitis B prevention program. Conversely, the perinatal hepatitis B prevention program can use registry data to identify outcomes for infants born to infected women who might have been lost to follow-up. Periodic cross-matches with local cancer registry and death certificate data can allow a program to estimate the contribution of chronic HBV infection to cancer and death rates. Guidelines that clarify how and when data with or without personal identifiers are transmitted and used should be developed to facilitate the protection of confidential data. Implementation of Testing RecommendationsHealth departments provide clinical services in a variety of settings serving persons recommended for HBsAg testing, including many foreign-born persons, MSM, and IDUs. Ideally, HBsAg testing should be available in venues such as homeless shelters, jails, STD treatment clinics, and refugee clinics because of the increased representation of IDUs and former IDUs in homeless shelters (58% drug users [137]), substance abuse treatment programs (13%--50% IDUs [138,139]), and correctional facilities (25% IDUs [140]) and the overrepresentation of IDUs and MSM in STD clinics (6% IDUs and 10% MSM [141]), prevalence of chronic HBV infection is likely to be higher in these settings. However, few states have resources to implement HBsAg testing programs in these settings and rely instead on limited community programs for needed public health and medical management. In 2008, CDC supported adult viral hepatitis prevention coordinators (AVHPCs) in 49 states, the District of Columbia, and five cities (Los Angeles, Chicago, New York City, Philadelphia, and Houston) who assist in integrating hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccination, hepatitis B and hepatitis C testing, and prevention services among MSM, IDUs, and at-risk heterosexuals treated in STD clinics, HIV testing programs, substance abuse treatment centers, correctional facilities, and other venues. AVHPCs can promote the implementation of hepatitis B screening for MSM and IDUs. Testing in refugee and immigrant health centers and other health-care venues is needed to reach U.S. residents born in regions with HBsAg prevalence of >2% (142); AVHPCs also can collaborate within these settings to ensure that persons from HBV-endemic regions are tested for HBsAg. CDC's perinatal hepatitis B prevention program provides case management for HBsAg-positive mothers and their infants, including educating mothers and providers about appropriate follow-up and medical management (143). This program currently identifies 12,000--13,000 HBsAg-positive pregnant women each year (CDC, unpublished data, 2007). Although perinatal prevention programs provide follow-up for infants born to HBV infected women, the majority of states and local perinatal prevention programs lack staff to offer care referrals for HBV infected pregnant women. Multiple health-care providers play a role in identifying persons with chronic HBV infection and should seek ways to implement testing for chronic HBV in clinical settings: primary care, obstetrician, and other physician offices, refugee clinics, TB clinics, substance abuse treatment programs, dialysis clinics, employee health clinics, university health clinics, and other venues. Medical compliance with testing recommendations already is high for certain populations, particularly among those who typically receive care in hospitals or other health-care settings in which HBsAg testing is routine. For example, 99% of pregnant women deliver their infants in hospitals and 89%--96% of them are tested for HBV infection (144; CDC, unpublished data, 2007), and susceptible dialysis patients are tested monthly for HBsAg (119). However, compliance with testing recommendations is lower in other settings. One study indicated that testing was performed for 30%--50% of persons born in regions with high HBsAg prevalence who were seen in public primary care clinics (145). Even in settings in which persons are tested routinely for HBsAg, more efforts are needed to educate, evaluate, and refer clients for appropriate medical follow-up. CDC supports education and training grants that help educate providers to screen patients at risk for chronic hepatitis B. Prevention research is needed to guide the delivery of hepatitis B screening in diverse clinical and community settings. In addition, community outreach and education, conducted through developing partnerships between health departments and community organizations, is needed to encourage community members to seek HBsAg testing. These partnerships might be particularly important to overcome social and cultural barriers to testing and care among members of racial and ethnic minority populations who are unfamiliar with the U.S. health-care system. Advisory groups of community representatives, providers who treat patients for chronic hepatitis B, providers whose patient populations represent populations with high prevalence, and professional medical organizations can guide health departments in developing communications and prioritizing hepatitis B screening efforts. The lack of sufficient resources for management of infected persons can be a barrier to implementation of screening programs. All persons with HBV infection, including those who lack insurance and resources, will need ongoing medical management and possibly therapy. This demand for care will increase as screening increases, and additional providers will be needed with expertise in the rapidly evolving field of hepatitis B monitoring and treatment. Acknowledgments The following persons provided consultation and guidance in the preparation of this report: Miriam J. Alter, PhD, University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Galveston, Texas; Mary B. Barton, MD, MPP, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Maryland; Molli C. Conti, Hepatitis B Foundation, Doylestown, Pennsylvania; Adrian DiBisceglie, MD, St. Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri; Kristen R. Ehresmann, MPH, Minnesota Department of Health, St. Paul, Minnesota; Susan I. Gerber, MD, Chicago Department of Public Health, Chicago, Illinois; Beau Gratzner, MPP, Howard Brown Health Center, Chicago, Illinois; Ken J. Hoffman, MD, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, Maryland; Jay H. Hoofnagle, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, Maryland; Sandra Huang, MD, San Francisco Department of Public Health, San Francisco, California; W. Ray Kim, MD, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota; Anna Suk-Fong Lok, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan; Brian McMahon, MD, Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, Anchorage, Alaska; Alawode Oladele, MD, DeKalb County Board of Health, Decatur, Georgia; Henry J. Pollack, MD, New York University Medical Center, New York, New York; Samuel So, MD, Asian Liver Center at Stanford University, Stanford, California; William Stauffer, MD, DTM&H, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota; Diana L. Sylvestre, MD, University of California, San Francisco, Oakland, California; Jonathan L. Temte, MD, PhD, AAFP Liaison to ACIP, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin; Ann R. Thomas, MD, Oregon Department of Health, Portland, Oregon; Amy E. Warner, MPH, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, Denver, Colorado; Isaac B. Weisfuse, MD, New York Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, New York, New York; John B. Wong, MD, FACP, Tufts New England Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts. References

* Disagreement exists internationally about best practices for avoiding transmission of HBV from health-care worker to patient (53). Table 1 ![TABLE 1. Estimated number and percentage of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)–positive persons, by population segment —

United States, 2006

2006 HBsAg–positive persons

population HBsAg prevalence No.

Population segment (millions) (%) (thousands) (%)

U.S.-born, noninstitutionalized* 254.3 0.1 356 (30–50)

(95% CI† = 0.1–0.2) (229–534)

Foreign-born§ 37.5 1.0–2.6 375–975 (47–70)

Correctional institutions¶ 2.2 2.0 44 (3–5)

Other group living quarters** 6 0.5 30 (2–3)

Total 300 0.3–0.5 805–1,405

* Source: 2006 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau. Excludes persons living in correctional institutions and other group quarters. HBsAg

prevalence estimates were derived from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (CDC, unpublished data, 2008).

† Confidence interval.

§ Sources: 2006 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau. Prevalence range represents estimates from the National Health and Nutrition

Examination Survey (1%) (CDC, unpublished data, 2008) and country-specific HBsAg estimates reported in the medical literature (2.6%) (CDC, unpublished

data, 2008), applied to the estimated population by country of origin. Infant immunization programs in many countries have led to marked

decreases in incidence and prevalence among younger, vaccinated members of these populations, which are largely not reflected in the medical

literature (Wasley A, Kruszon-Moran D, Kuhnert W, et al. Hepatitis B prevalence in the U.S. in era of vaccination [Abstract 723]. 45th Annual Meeting of

the Infectious Diseases Society of America, San Diego, California; October 4–7, 2007).

¶ Sources: Sabol WJ, Minton TD, Harrison PM. Prison and jail inmates at midyear 2006. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice

Statistics, Office of Justice Programs; 2007. Available at http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/pjim06.pdf. CDC. Prevention and control of infections

with hepatitis viruses in correctional settings. MMWR 2003;52(No. RR-1).

** Includes college dormitories, military quarters, nursing homes, group homes, and long-term care hospitals, as well as homeless persons. For persons

in other group-living quarters, estimated HBsAg prevalence was assumed to be equal to the mean prevalence in other groups. Source: 2006 American

Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau.](figures/r708a1t1.gif) Return to top. Figure 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top. Figure 2  Return to top. Table 3  Return to top. Figure 3  Return to top. Table 4   Return to top. Table 5  Return to top.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Date last reviewed: 9/4/2008 |

|||||||||

|